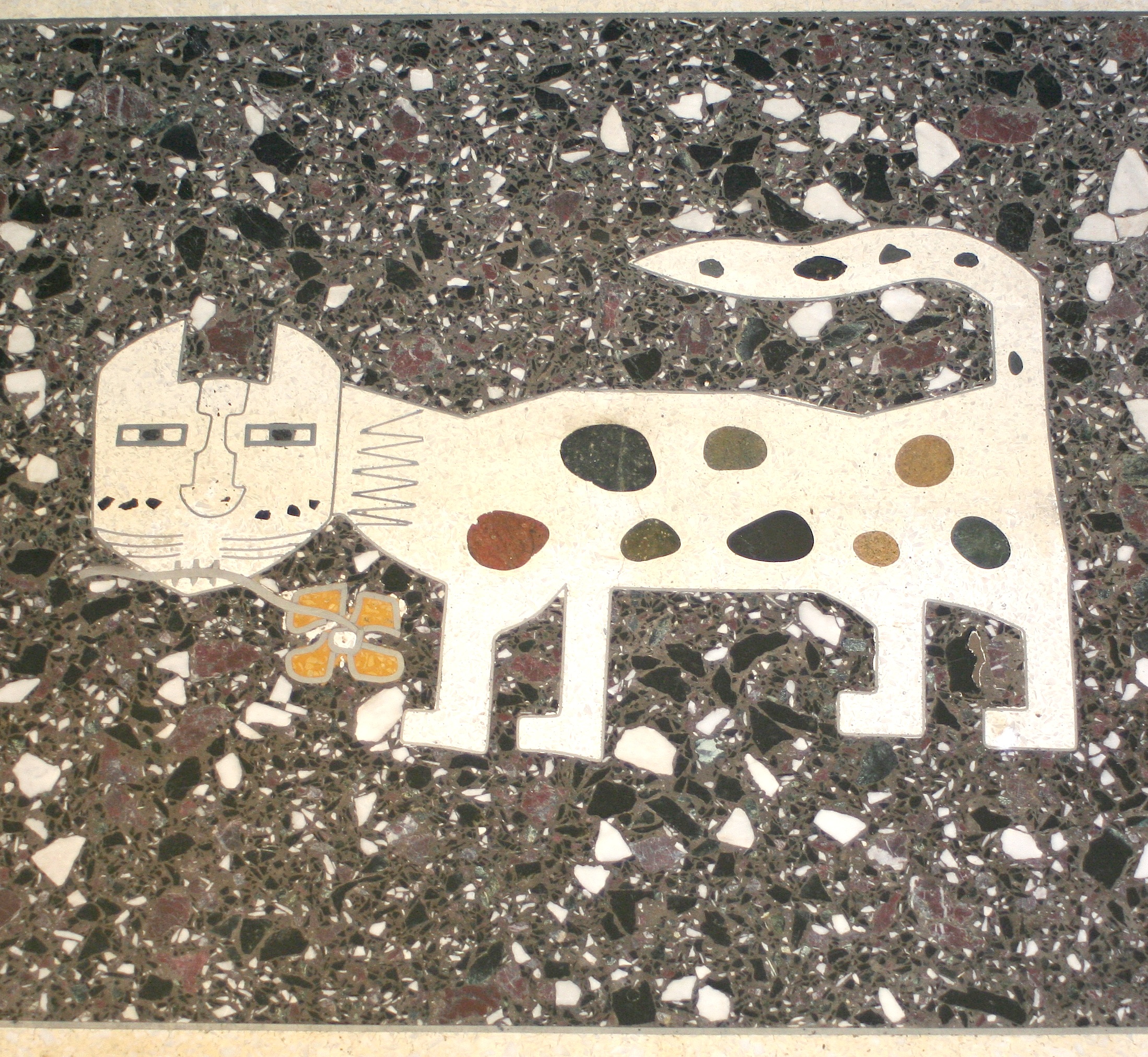

Producing these intricate mosaics required a lot of work — negotiating with Home Savings about the location and design; creating a sketch; transforming the sketch into a full-color gouache; making a slide, to project on the wall to form a full-scale cartoon; tracing that cartoon in reverse, marking the colors, and then transferring it to the floor, where the tesserae could be cut and pasted in sections, only to be assembled on site into a right-side-up, all-mortared-together mosaic.

Needless to say, if one individual tried to do all that work alone–and then add architectural elements, stained-glass windows, decorative insignia on the doors and windows and cornice–it would take years, if not decades, to complete.

Some of that assistance might be seen as incidental to the artwork–I am no mason, but laying the mortar seems more workmanlike to me, for example–but others involved in the translation of idea into realized artwork clearly had to be artists in their own right.

While Millard Sheets was the face of the studio and the source of many of the designs, his closest collaborators were Denis O’Connor and Susan Hertel. Hertel was a painter in her own right, who worked in the studio creating the large-scale cartoons and doing most of the color selection; those I have talked to say her human figures are distinctive for their flowing lines. O’Connor, who had trained in the Royal Academy of Arts as a sculptor but had won drawing awards there, came to Claremont in 1960 and began work on the mosaics. And O’Connor and Hertel continued to work together on projects for Home Savings after Millard Sheets closed out his interest in the studio, in 1980.

Thus, when we look at the Home Savings art and projects like them, we have to keep in mind there is a vast team, including many artists, working together, and that the final signature — in this case, those of Hertel and O’Connor, indicating they may have conceived the design from start to finish — only reflects one or two of those involved with the work.

This week I had a chance to sit down with Denis O’Connor’s son, to hold some of the tesserae from the mosaics in my hand, to discuss the specific processes of making the tiles level and the design realistic. He has a great painting by Susan Hertel, showing the process of mosaic making — the work of men and women sitting around on the floor, surrounded by numbered cans filled with tiny pieces of glass, snippers in hand and the wheat paste nearby. I hope to speak to more of the mosaicists soon, but clearly a lot of drudgery came between conceiving of the design and seeing the final product, gloriously installed.

In terms of the artistry here in Tujunga, there are some interesting signs of the collaboration: the flowing plants and maternal figures, present in many of Hertel’s works, sit within the overall outline of a tree, a later and more sophisticated choice of design than the early, square mosaics. Millard Sheets collected Native American art, especially from the pre-Columbian period, and this work shows echoes of a large painting, signed by Sheets, in the Pomona First Federal building in Claremont, showing American Indian men gathering horses, and American Indian women, some bare-breasted, sitting in a circle.

Here, a Native American man holds a bow, while a Native America woman sits with a basket — perhaps reflecting the lifestyle of the Tongva, who gave the area its name. To the right, a vaquero roping a bull reflects the later Californio period. Do the stalks between them reflect wheat or bullrushes, agriculture or river foliage? Do most of the figures face right, to show the passage of time in that direction, or do they not engage one another to show a hostility, a pain between these communities? As I work with the preliminary sketches and correspondence about these images, I hope to find some answers.