Happy Thanksgiving Weekend!

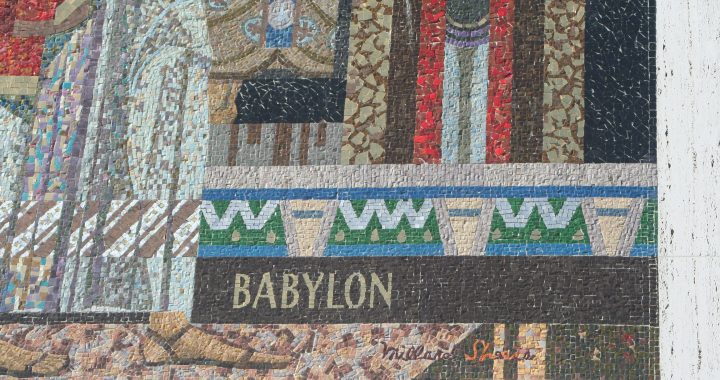

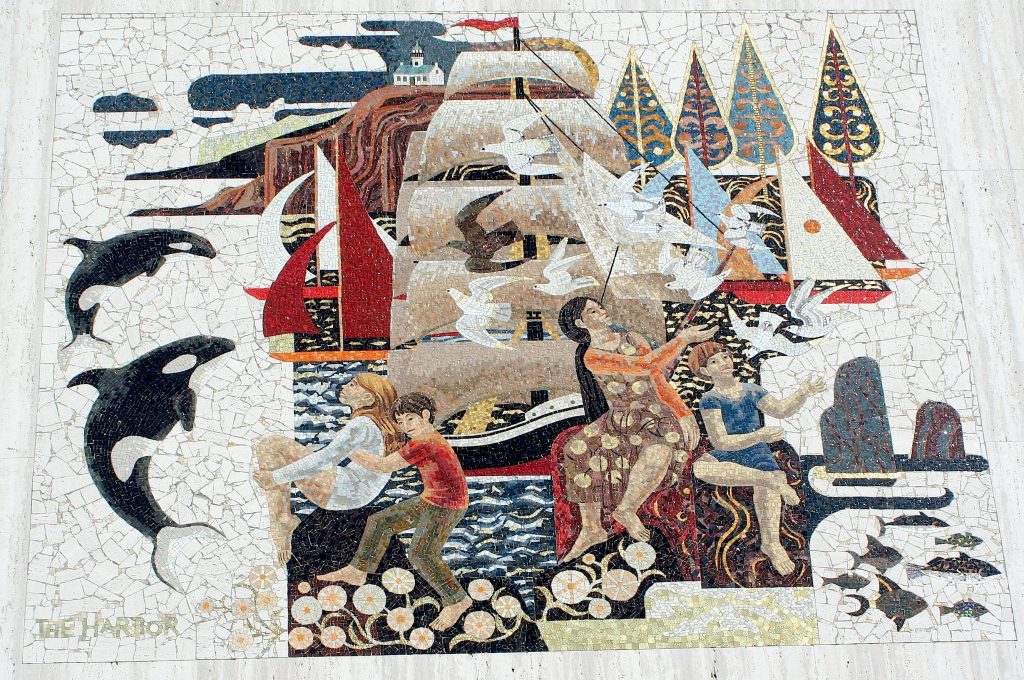

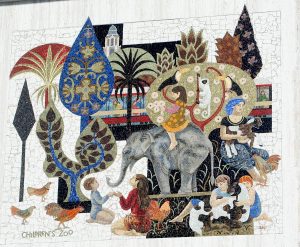

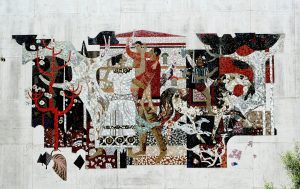

While I am at home in San Diego, I thought it was worth going back to the original Home Savings and Loan bank. In the future, I will post more about the original Home Savings mosaic, and the iconic gold HS&L tiles that flanked the other artwork and ran beneath the windows on the bank.

But today I want to focus on what surprised me most when visiting the bank this month: the stained glass. I have written about the importance of stained glass at a number of marquee Home Savings locations, and I have found other inaccessible pieces of stained glass.

But the original branch held a double surprise for me: the answer to one riddle, and the beginning of the next .

First, the new riddle: why are so many of the stained-glass windows blocked off? This is somewhat an answerable riddle, by the simple fact that many of them, as here and at Laurel Canyon, reach the full height of the building, and so when renovations are made and second floors become inaccessible to the general public, the glass gets blocked off.

The image above tries to solve this problem by taking the external image–showing the full extent of the window–and reversing it; hence, if you go to see it, those captions will be only visible from inside.

The placement of the new stairway and drop ceiling on the inside make it impossible to see the captions, and I am pretty sure the clear, etched-glass sections are not original, and must replace either broken windows or windows that held Home Savings logos (more research awaits, as always).

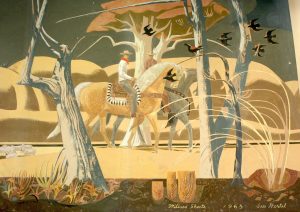

But I knew there were captions, and I could make out what I was seeing here, thanks to an early image I saw at the Millard Sheets Studio in Claremont: a single panel of stained-glass work, showing the (Biblical?) scene of an Egyptian-dressed man carrying a calf over his shoulder, with the caption “banking.”

Clearly, this was artwork intended for another project that did not make it–but I also found it a fitting reminder within the Claremont studio of the primary client and benefactor, Howard Ahmanson and his banks. Given what Sheets says about his work on this first bank, I think this window could have gone all the way to fabrication before some design change meant it could not be installed in this bank as planned.

What to make of the imagery? Well, banking is an obvious subject for a bank, and the fine-art quality of these stained glass windows shows the initial desire to make these banks places to linger, to experience beauty. Such a universal history of banking hardly seems to engage the community and the location; of course, this was the first bank, and so those imperatives may not have been clear yet.

The Sheets Studio designed these windows but did not fabricate them; soldering and glass-cutting went on in Pasadena, though Katy Hertel remembers her mother going down to paint all the details onto the glass, so these works can clearly be considered as part of the overall Sheets Studio package. It is very hard to see enough detail here to really be sure, but these windows do not seem to share the style of the later Sheets Studio art–but neither, really, does the mosaic out front, which was fabricated in Italy. (More on all that in the weeks ahead.)

The placement of this window also indicates a pattern present here and at Laurel Canyon, and at Sunset and Vine: sculpture and mosaics in front, stained glass catching its light over the parking lot. That might have been about security for the artwork, but it also suggests the old cathedral trick of the rose window: catch them by surprise with the stained glass. You saw the mosaic out front, you pulled your finned car around to the back, you went in to bank, and then WHAM! on the way out, you look up to a beautiful image you are surprised not to have noticed before, over the door.

So many of these Home Savings banks have been remodeled, and the open doors have been changed, but it is worth considering how the art and architecture work together to create this spectacle.