The last Home Savings and Loan completely conceived by the Millard Sheets & Associates, in concert with Frank Homolka & Associates as the architects of record, was the expansion and renovation of the Encino branch at 17107 Ventura Blvd.

This branch has practically a whole wall of stained glass, mosaics inside and out (though the interior vault mosaic is now hidden), a large interior mural, and statues in niches — as well as a pair of ceramic mountain lions, enclosed in decorative grilles. Given the volume and variety of Sheets Studio artwork in this branch, it may be the most comprehensive look at the Sheets Studio’s production, given the variety of subject matter as well as media.

The year 1976 was one of the busiest for the Sheets Studio with Home Savings; we have seen artwork conceived or completed from that year in La Mesa, San Francisco, and Tujunga, with other projects in Alhambra, Redlands, Torrance, Buena Park, La Mirada, Lakewood, Simi Valley, Menlo Park, and Barstow still to come. It was also the era of the press-release or brochure at the opening, to give us a sense of what we see:

Designed for Home Savings by noted artist Millard Sheets, the two-story building occupies 12,030 square feet…

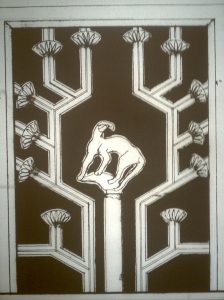

Two forty-foot[-]tall cast stone grill[e]s, designed by Tony Sheets, embellish the exterior while shading the large picture windows behind them.

Sculptress Betty Davenport Ford created two 1000[-]pound mountain lions which are ensconced on pedestals in the grill-work. Each larger-than-life animal was directly modelled from clay, slip-glazed and fired. They represent some of the largest works of this kind ever executed.

Like Sam Maloof, Martha Menke Underwood, and some of the other of the very best Pomona Valley artists, Betty Davenport Ford spent a period of her career contributing to the Sheets Studio artwork before dedicating herself completely to a solo career, creating sculptures of the natural world, distinctively stylized. At 88, she is still involved with the world of art ceramics, and her work is present in museum collections around the country.

These lions provide an interesting twist on the idea of connecting to the community. The winged lion of St. Mark, as seen in Venice, Italy, was the symbol of Home Savings, but this large cat is a local–to this day, the San Fernando Valley is sometimes visited by the region’s mountain lions, this big in the minds of the suburbanites who encounter them (though not this large in reality.)

I have to think more about if the art of the Encino branch has a unified narrative–from mountain lions to working men and women, to farm animals and birds to a cowboy on horseback–but the lion could mark the earliest, primeval sense of the valley, especially given the local La Brea tar pits, and the remains of the megafauna–saber-toothed cats, wooly mammoths, dire wolves, etc.–that were found there in number. It takes the winged lion and says hey — take a look at this local lion instead!

Though partially hidden by trees now, these lions in Encino announce proudly how Home Savings would guard that money.