Home Savings tower, Pomona, 1963

In the past month, scaffolding has gone up around the Home Savings tower in Pomona, at the corner of Second and Garey. Local preservationists were disturbed at this development; less than fifty years old, and part of the modernist moment in art and architecture just now being preserved in Pomona, Los Angeles, and across the nation, they were worried about what exactly was going on. (See news and comment.)

Questions have been raised, from what is Chase Bank’s intentions, to whether such a tower is worth preserving. So this week I will take those ides on–in reverse order.

Why preserve this tower? Well, the first thing to know is that it was conceived as part of the same project as the Pomona downtown mall, a novel project for its time in using the allure of downtown, plus a few fountains, sculptures, and mosaics, to draw in locals on their lunch break and visitors to town. Built as a pedestrian mall, the Pomona downtown mall was one of the earliest examples of the attempt to replicate the shopping Main Streets that anchored thousands of U.S. towns in the era before the highways overran that landscape.

If that doesn’t speak to you, consider the building’s interior:

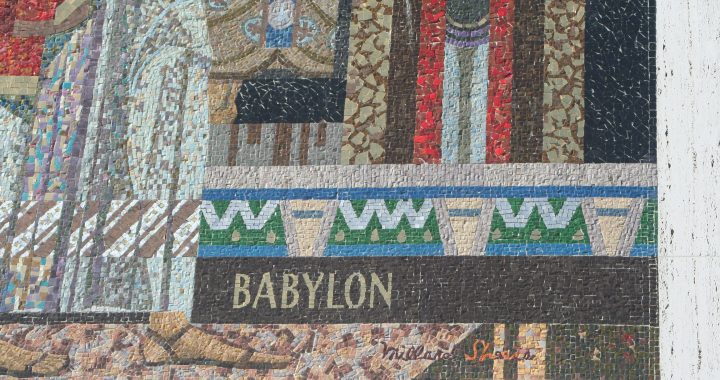

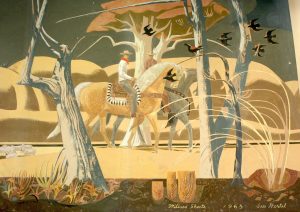

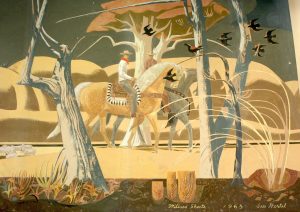

Susan Hertel and Millard Sheets, Pomona, 1963

A wall-to-wall painting by Millard Sheets and Sue Hertel, one of the first (if not the first) which she signed, marking her transition from Scripps College art student to full-fledged member of Sheets’ artistic studio. The jagged-shaped birds, rolling abstract hills, and horse motifs seem very much like Sheets, but there is a warmth, both in this painting and the outside mosaic.

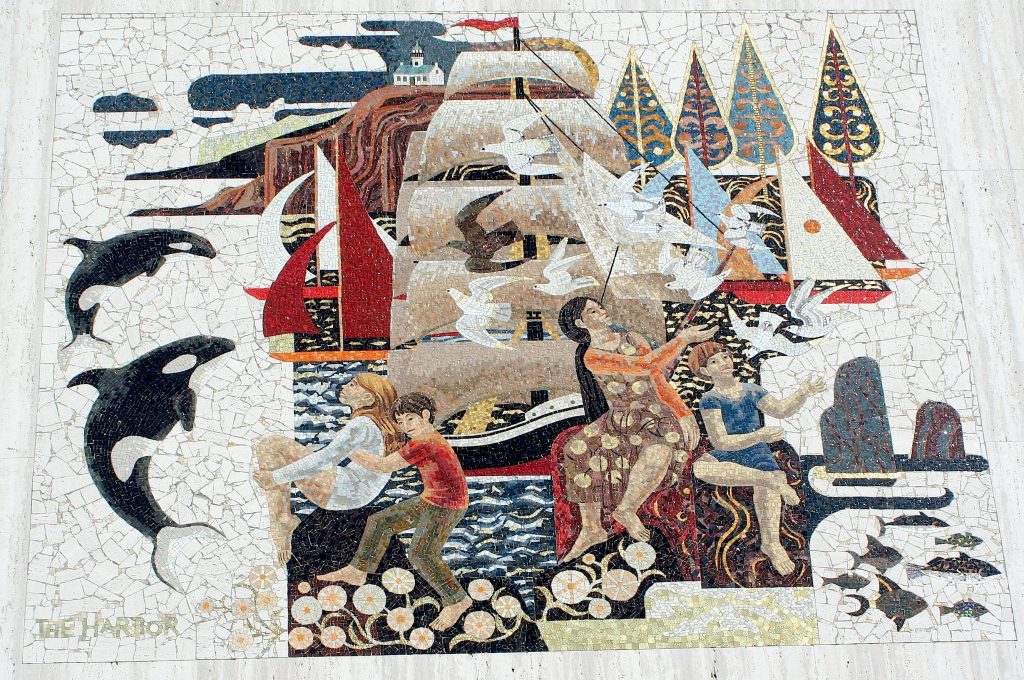

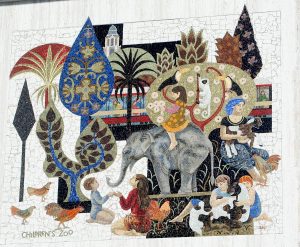

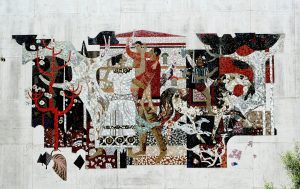

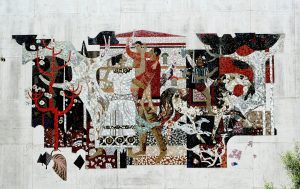

Pomona mosaic, 1963

This suggests the scenes of family embraces, curvilinear, organic shapes, and subtle but striking color choices that would mark much of Hertel’s best work as a painter and Studio member for decades to come.

The mosaic is near-impossible to remove; as long as the building is standing, it will be there, one assumes. And the painting, though massive, must have found some way in; it is probably on panels, and so, if Chase needed to remove it, it could.

But that leaves the overall design of the building itself, something no one photograph can really capture. Once you look closely at the window latticework, you can see the H-S of Home Savings, one of the marks of the early, “signature” banks personally overseen by Millard Sheets and Howard Ahmanson. (Some of the later iconic elements — a golden lion of Venice symbol by the door, and the marble facing — are also present.) As some have noted, Sheets’ Studio provided artwork for about 160 banks, but the partnership of Ahmanson and Sheets only worked comprehensively on about 45 banks, before Ahmanson died in 1968.

I have not been inside the upper floors, so I have no idea what it is like to work there today; it is a modernist icon, but like many modernist architectural icons, the spaces could be poorly adjusted to the needs of modern office life, or they could be perfect.

My first hunch is that the scaffolding is nothing to worry about; Chase Bank has had trouble with the painting over of a fresco mural in San Francisco, and the removal of the paneled mural in Pasadena, but it seems Tony Sheets (Millard’s son) has been able to work with the company — when the public and the media are alert enough to get him involved. And there is the California Art Preservation Act, which (with its federal counterpart) should at least help slow any changes to a considered pace.

But what is really needed is a true commitment from Chase Bank, to learn about the work of the Millard Sheets Studio, and to create a general plan for how the bank will steward this art and artwork.

The Sheets Studio work was the pride of Home Savings, financed, researched, carefully crafted, lovingly maintained, even through remodels. Washington Mutual, by all accounts, was quite aware of this heritage when they bought the banks, and they seem to have considered how best to maintain that Home Savings ambience in these branches.

But Chase, on the other hand, seems to have brought in their own models, angering customers and losing the local touch in the meantime. This very Pomona branch has a key example:

Pomona painting and Plexiglass, Chase Bank, 2010

The Plexiglass that Chase has installed in front of the tellers, distorting and blocking the view of the Sheets-Hertel painting. The same seems to be true in many of their bank locations — the need to place white-and-blue themes, the perfect logos, and these Plexiglass shields (which of course make me feel less safe when I am banking, because the bank is telling me there is something to fear). Home Savings intended their banks as a place individuals could spend time, discussing their investment options, resting their feet, enjoying the “living room” feel; Chase seems to want you to come and go quickly, and if you want a personal touch, perhaps the ATM would be better.

Somewhere, Chase has the institutional records of Home Savings; through projects like mine, and interviews with those involved in the creation and preservation of this art and artwork, JP Morgan Chase Bank could be part of the process of honoring and understanding the gift that Howard Ahmanson, Home Savings, and the Millard Sheets Studio gave to California. In a few cases, Chase has made the effort and paid the expenses for restorations — but these are counterbalanced by the ignorant mistakes made to destroy the artwork in other branches, the lack of communication in cases like Pomona.

So the scaffolding in Pomona can be a wakeup call — both to alert preservationists and bank customers, to ask questions and be sure to announce any such changes. But more importantly, it should be another chance for Chase Bank to truly engage with the history of the art and architecture of the Sheets Studio banks — and to have a chance to be part of the community , as Home Savings and Washington Mutual were, aware of the local history and tradition — and not just another anonymous, disliked national chain.