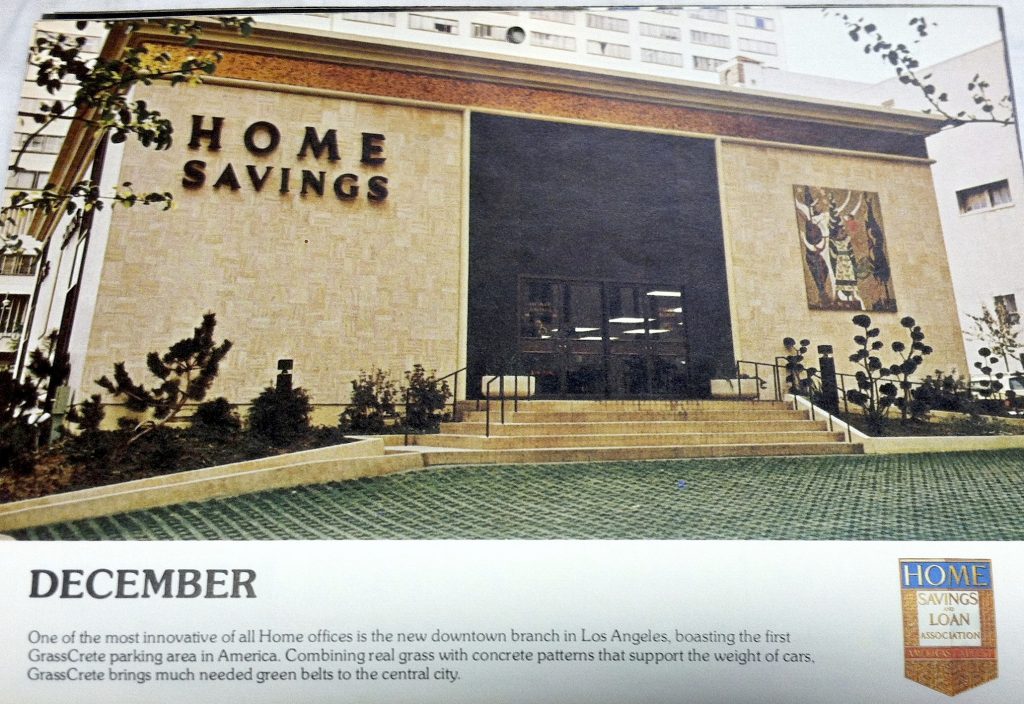

Grasscrete at the Los Angeles Downtown Home Savings

GrassCrete at the Los Angeles Home Savings, 7th and Figueroa (demolished). 1977 Home Savings calendar, courtesy of George Underwood

When discussing the mosaic panels once at 7th and Figueroa, I thought of this image, of the Grasscrete parking surface once used at this location. (It also confirms the mosaic’s placement at that site, before removal.) A colleague at the L.A. Conservancy said this was her strongest memory of visiting this branch in the 1970s and 1980s.

As the caption from this 1977 calendar proclaims, “combining real grass with concrete patterns that support the weight of cars, GrassCrete brings much-needed green belts to the central city.”

GrassCrete seems to be the brainchild of the Bomanite corporation, one of their ways to create “ornamented concrete.” Boman was an artist turned industrial contractor — clearly, a career path Millard Sheets would have admired.

The number of marketers and technical papers online suggest it is still possible to order and install GrassCrete, which I have encountered, here and there, in public plazas.

One wonders why (cost? impracticalities? mud?) this simple way of greening parking lots and sidewalks did not catch on.

Ghosts of Home Savings: Bay Area Finance and First Federal

S. David Underwood & Millard Sheets Studio, Fred L. Roberts Enterprises-Bay Area Finance, Wilshire Boulevard, Santa Monica, built 1957, photo 2012.

To continue looking at the work of S. David Underwood as principal architect for the Sheets Studio, I present these buildings, built (and unbuilt?) for financial institutions other than Home Savings.

First, the built: a delicately curving building at 1619–1621 Wilshire Boulevard in Santa Monica. The color logo tiles and the terrazzo floors being the best hints at this building’s Mid-Century Modern past — given that the inside spaces were long since gutted. Note also the alley-side view in the picture above: for a building not on a prominent corner, the marble siding stopped when the facade did.

Sheets Studio, logos for Fred L. Roberts Enterprises and Bay Area Finance and “JI,” Santa Monica, built 1957, photo 2012.

The tile logo letters show an attempt, contemporaneous to the Home Savings work, to find a quick, recognizable way to mark the business with a colorful, artistic icon — closer to the style of abstracted corporate icons for franchise recognizability that has become a permanent part of U.S. roadside architecture, from the Golden Arches to the Swoosh to JP Morgan Chase’s interlocked pipes-become-octagon.

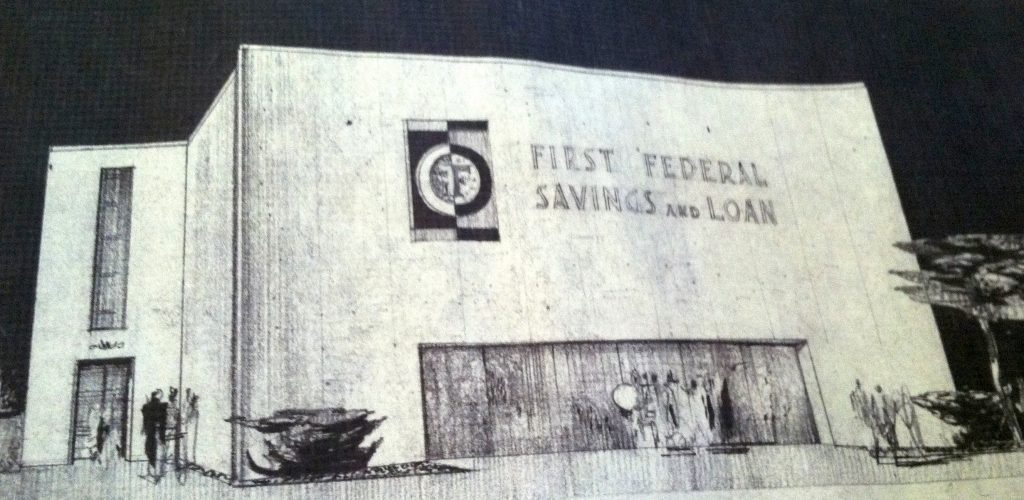

Could such a logo have worked for a bank in the 1950s? This sketch, for an apparently unbuilt First Federal Savings and Loan (perhaps intended as a branch for the bank in the larger Dallas project where Sheets and Turner met) shows a bank design much like the Home Savings banks, but with such a logo instead of mosaics or the gold tiles. (It reminds me of I.Magnin store designs, and others on view here.)

These works show that, while the art and architecture being created for Home Savings was the most prominent and memorable of the Sheets Studio work, those other projects, designed by Sheets and Underwood and completed by others in the Studio, demonstrate the wider role of their architecture in shaping the Mid-Century Modern look of commercial spaces, in Los Angeles and beyond. We can hope these contributions will be included in the exhibits, lectures, and discussions around the Getty’s Los Angeles Architecture initiative next spring.

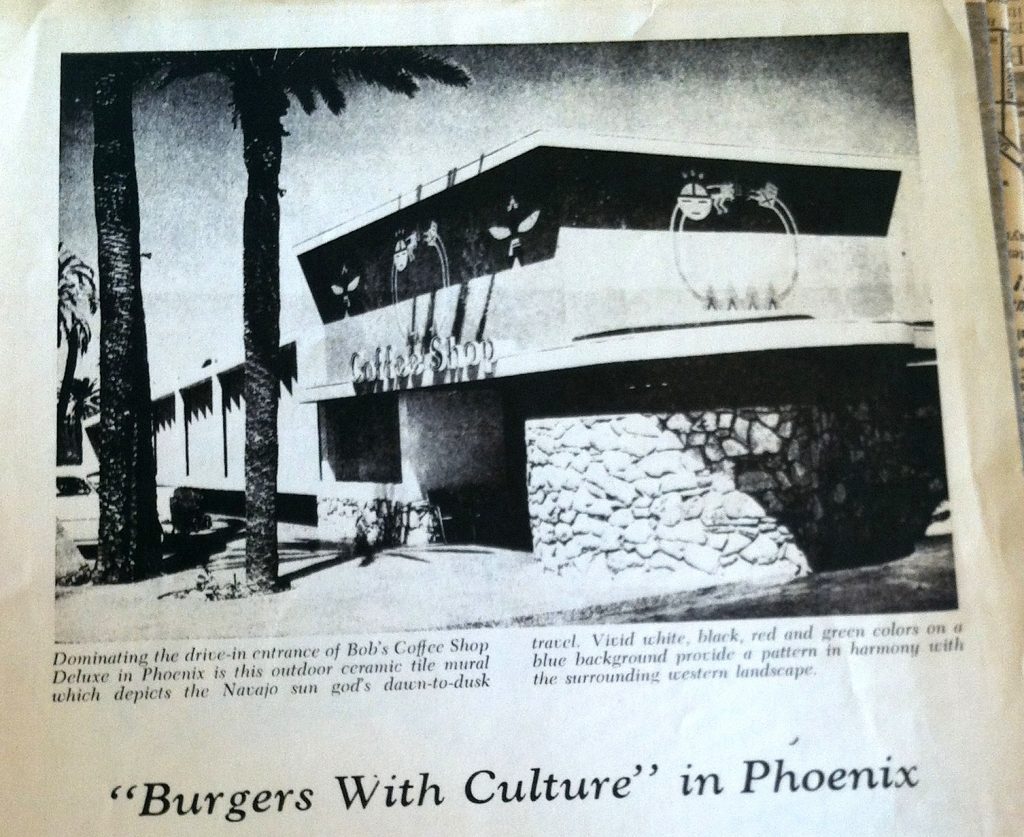

Bob’s Big Boy “Burgers with Culture” in Phoenix

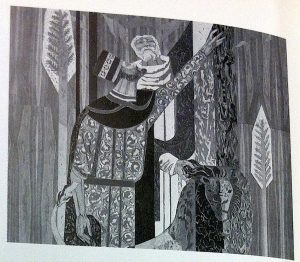

Millard Sheets Studio, Native American themes in mosaic, Bob’s restaurant, Phoenix, 1954. From “Burgers with Culture,” TILE Magazine, 1955. S. David Underwood Archive.

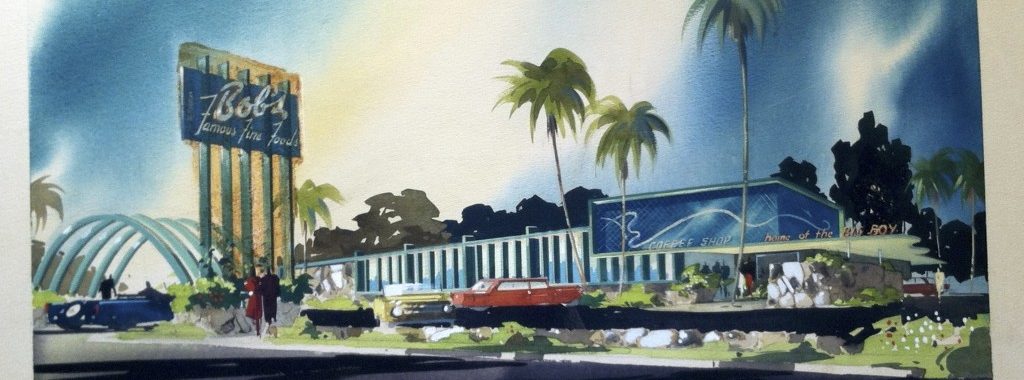

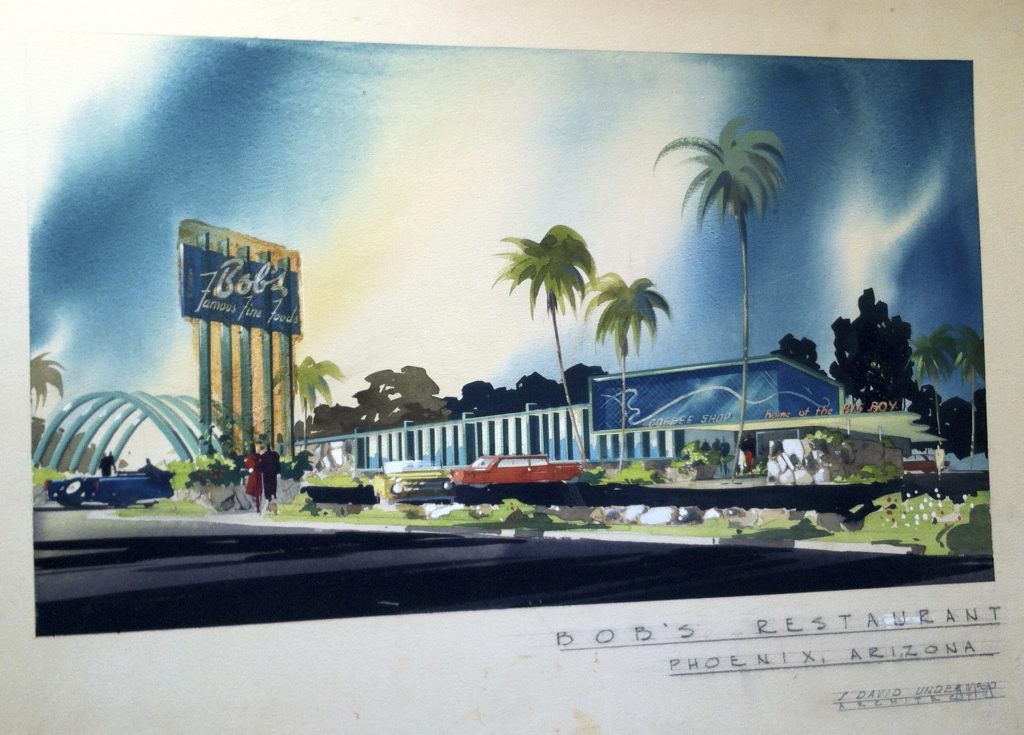

As discussed last week, S. David Underwood, the Sheets Studio’s principal architect, got his break working for a Glendale chum, Robert C. Wian, as he expanded Bob’s Big Boy into an iconic franchise.

The Bob’s Big Boy in Burbank is a Googie icon, designed by Wayne McAllister, is a historic landmark. But the Phoenix’s Bob’s restaurant, designed by Underwood — which had mosaic work designed by Millard Sheets — seems to have been destroyed.

Underwood’s extant drawings show the Phoenix franchise was conceptualized as a near-copy of the Burbank location, but that subsequent designs changed the elements, though still within the Mid-Century Modern/Googie/drive-in styles.

S. David Underwood, Sheets Studio, sketch for Bob’s exterior, Phoenix. c. 1954 S. David Underwood Archive.

A large, billboard-like neon sign with the Bob’s name, arches flying over the driveway entrance, and alternating black and white panels mix the feel of Sheets Studio designs–and this was one–and the Bob’s Big Boy checkerboard pattern. Sketches and photographs show how the wall design and counter layout were all carefully planned, with the Sheets Studio sense of interior precision.

S. David Underwood, Sheets Studio, sketch for Bob’s interior, Phoenix. c. 1954 S. David Underwood Archive.

But what might surprise even the Bob’s aficionados is the Millard Sheets-designed mosaic of Navajo, Apache, and Pueblo (or Hopi?) “gods and legends,” known to us through this September 1955 article in TILE magazine.

The largest mosaic, seen above, depicted sun symbols and used background tiles from the Mosaic Tile Company, mosaic “specks” (their word) and ceramic cast pieces designed by Sheets and made at the LA County (Otis) Art Institute under the supervision of W.A. Perry, whose tile and marble company on E. Indian School Road in Phoenix then completed the installation. (This is more interesting data for the discussion of who fabricated the mosaics in the Sheets Studio before the arrival of Denis O’Connor in 1961.)

Though we only have a black and white photograph, the TILE magazine caption sounds like classic Sheets Studio work: “Vivid white, black, red and green colors on a blue background provide a pattern in harmony with the surrounding western landscape.” Sheets himself is quoted in the article discussing the tile’s durability, suggesting such outdoor, artistic use was unfamiliar. As for the American Indian nations as the source of a theme, Sheets had designed the Thunderbird air fields in the California and Arizona deserts and utilized Native American imagery there as well.

Where is this work now? This restaurant was at N. Central Avenue and E. Thomas Road, which Google StreetView suggests two massive office buildings, an empty greenspace, and a strip mall exist today. So chalk this up as another lost Sheets artwork.

S. David Underwood, Sheets Studio Architect

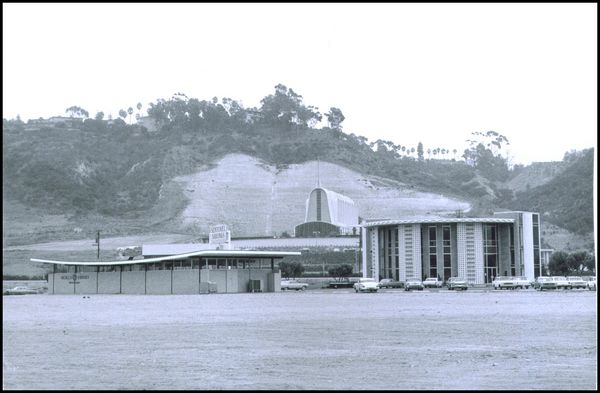

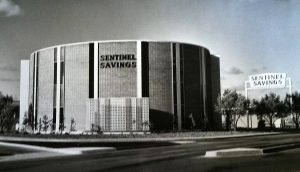

S. David Underwood, Sentinel Savings and Loan, San Diego, 1962 (demolished); photograph by Busco-Nestor Studios. S. David Underwood Archive.

In July 1948, Millard Sheets typed up a followup note to Jack Beardwood, a TIME bureau chief and Millard’s connection to LIFE magazine. “It just occurred to me,” he wrote, ” it might be wise to suggest…that the magazine should not use the word ‘architect’ in the article in connection with my name.” As Sheets noted, “not having an actual architectural degree, along with many others who design,” he had no need to claim the title and “wav[e] a red flag in front of the A.I.A.,” architecture’s national professional association.

Sheets made clear that he did the overall design, approaching it as art in its totality–but that there was always an architect there to sign off, to make working drawings, and to see to it that regulations were followed. In the letter from 1948, Sheets mentioned Benjamin H. Anderson as the architect of record on the air school projects; as we have discussed here, Rufus Turner has shared memories of the studio beginning in the late 1950s.

But, as soon as there was a Sheets Studio to be part of, the studio’s principal architect was S. David Underwood. Rufus Turner has memories of seeing Underwood hard at work in Sheets’s large personal studio at the Padua Hills house–and even of Underwood having a cot there to sleep, before the Foothill Boulevard studio was constructed, after a 1958 groundbreaking.

Born in Montreal in 1917, Underwood had grown up in Glendale, California, and his first commercial architecture was for a schoolmate, Robert C. Wian, designing distinctive, “landmark” architecture for the new branches of his hamburger stand, Bob’s Big Boy. This iconic work (see next week’s post) stood out among roadside architecture, much as Sheets would need for Home Savings.

Underwood came to work with Sheets in 1955, just as Sheets’s work in murals and interior design was blossoming into the design of complete buildings, with the mainstay of the office’s work, at the behest of Howard Ahmanson, begun with a phone call in 1953, for both Home Savings (Underwood worked on 16 locations, 1956-1962) and Guaranty Savings and Loan (three locations, including Redwood City) in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Underwood made all this work possible, Sheets understood. Millard wanted to sketch the silhouette of the building and design its artistic flourishes, but he wanted someone else to decide how to route the pipes, support the roof, or create drawings for permits and contractors. This synergy of vision and technical details was all necessary for the art to emerge–and the next few weeks will highlight these designs, from subtle to spectacular.

Like the work of Sue Hertel, Denis O’Connor, David’s wife Martha Menke Underwood (married in 1962, they divorced in 1979) and others in the Sheets Studio, Dave Underwood’s work was publicly regarded as Millard Sheets Studio work, without much room for individual credit.

By 1962, Underwood left the studio to set up his own architectural office in Claremont, though he continued to collaborate with Millard Sheets on some projects, including the Garrison Theater (updated link here). Underwood continued to design buildings, including a lot of distinctive office space in Claremont, including the San Jose Avenue office building for the Carpenters’ Union (updated link here), and the Midland Mutual Insurance building at Harvard and Fourth, until his retirement in 1990. Underwood died in 2002.

As all the references above suggest, there are a lot of buildings I could have chosen to introduce Underwood on the blog. But one stood out–because it was a memorable landmark of my childhood.

S. David Underwood, Sentinel Savings and Loan, San Diego, 1962 (demolished); S. David Underwood Archive.

The Sentinel Savings and Loan building was built on Camino del Rio North in San Diego, near the intersection of Interstates 8 and 805 was constructed in 1962, one of Underwood’s first projects to be listed under his own architectural firm, after his time with the Sheets Studio.

As this photograph demonstrates, by 1965 the Sentinel Savings building anchored a trio of distinctive modernist structures in Mission Valley. In 1971, Sentinel Savings was purchased by Great Western, the name on the building in my childhood. Of these three, now only the First United Methodist church remains.

Though quite different from the Sheets Studio architecture for Home Savings, the clean geometric lines, use of solid and airy forms, and the use of the tall interior space suggested some of the same eye-catching choices, and show also the affinity of all this bank architecture to some of the most well-regarded examples of Mid Century Modernism. (See this example, a round bank in Sunnyvale from 1963 — is there some direct link to Underwood?)

Come back over the next few weeks to see more examples of Underwood’s work, before, during, and after his Sheets Studio work.

Thanks to Brian Worley, Rufus Turner, Steve Underwood, “Adrian Chapelo,” and Jane Kenealy of the San Diego History Center for their help with information for this post.

The Permanent Home for Temporary Mosaics: Home Savings’s Last Headquarters in Irwindale

For decades after its acquisition by Howard Ahmanson in 1947,Home Savings and Loan had its headquarters along Wilshire Boulevard — first in Beverly Hills, and then in Los Angeles, and finally, in 1985, to a campus in Irwindale. When Home Savings was purchased in 1998, the headquarters was transferred to Washington Mutual.

Now they are two of the three buildings in the renamed San Gabriel Valley Corporate Campus, its office suites are leased by CBRE, the large commercial real-estate services firm (which also manages former Home Savings properties in Coronado, Santa Monica, and Montebello, among other locations, sold by Home Savings to Met Life in the 1980s).

Some wonderful art–mosaics, paintings, fountains, and sculptures–were commissioned for the campus from Joyce Kozloff, Richard Haas, Astrid Preston, and others. (A nice post and illustrations of Kozloff’s work from friend-of-the-blog Vickey is here.) All of it seems to be still on site except the Preston works from the cafeteria walls, which JP Morgan Chase took after they acquired Washington Mutual, and no one quite seems to no where they went. (Leads, as always, welcomed.)

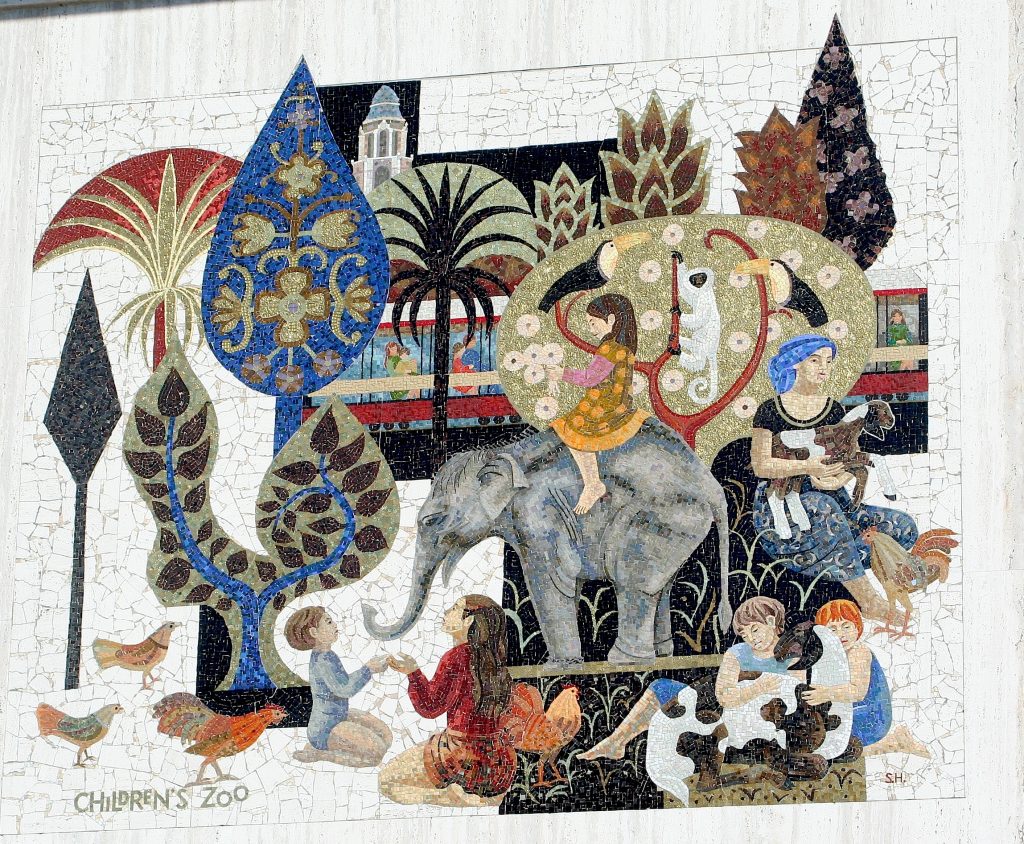

But the most remarkable find on campus for me were these three mosaic panels, installed on a brick wall to the right of the second building’s entrance. Showing a woman and children on horseback, a woman lifting a child into a tree, and a Dalmatian frolicking alongside, these joyous mosaic panels highlight the family themes so common in Sue Hertel’s work for the Millard Sheets Studio, as well as the angular trees, touches of gold, and intricate patternwork that Sheets himself was fond of.

Unlike any other Home Savings work I have seen, the panels are signed MSD — for Millard Sheets Designs, perhaps marking another moment in the evolving attributions in the Studio’s mosaics, from just Millard’s signature to a period of no signatures and then works completely designed, fabricated, and signed by Sue Hertel and Denis O’Connor. (In this case, Brian Worley has a distinct memory of doing that Dalmatian.)

These are intimate family scenes, but not linked to any specific place. To me, they suggest Sheets Studio designs elsewhere: the woman holding the child echoes Burbank and Pomona, while the children on horseback in a forest echo Burbank and Highland Park. A number of Sue Hertel’s designs show frolicking animals; for dogs, the Studio City stained glass and the mosaic in Anaheim come to mind.

These hints, once matched with Brian’s recollections, helped me realize what they are: the temporary mosaic panels, made in frames and intended to be installed in temporary Home Savings branches throughout the Southland, while their permanent buildings were built. (My research suggests they were built for a temporary location in downtown Los Angeles, possibly at 7th and Figueroa, 1974, and may have been displayed at later temporary branches in Westminster, Riverside, and Santa Cruz.)

I can’t say this is the most prominent file home for these mosaic panels, but they do seem appreciated by CBRE, on a campus that once thronged with Home Savings employees.

Thanks to Jason Bonomo of CBRE for giving me a tour of the Home Savings artwork on the property, and to Brian Worley for helping to identify the panels.

On Campus: Sheets Studio Artwork Found (and Lost?) at Mt. SAC

With the semester well underway, I am spending time on my campus, grading and teaching, which made me think of one of the campus art completed by the Millard Sheets Studio.

The Garrison Theater and other spaces around the Claremont Colleges come first to mind, along with “Touchdown Jesus” at Notre Dame and the tapestry in the Foley Communication Arts Center at Loyola Marymount. But Mt. San Antonio College (lovingly called Mt. SAC by those in the know) provides a few intriguing examples — and a question of missing art.

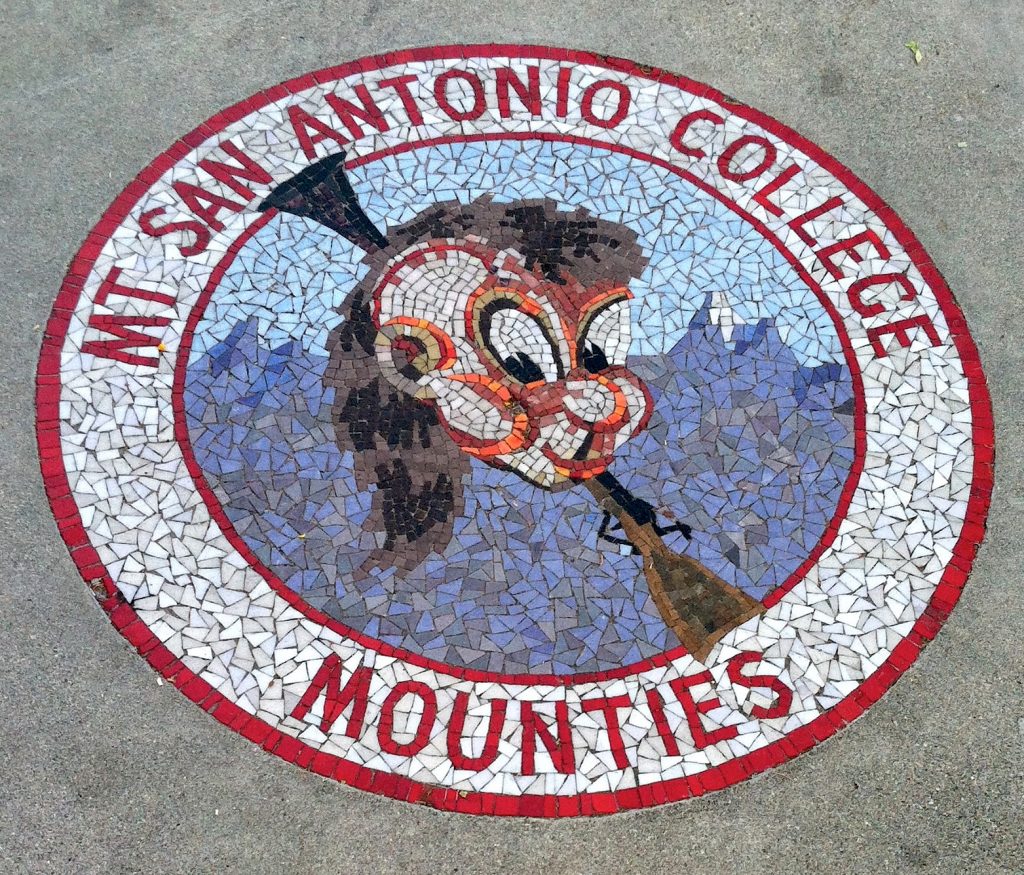

As you walk into the newly renovated Mt. SAC library, there is a brightly colored mosaic of “Little Joe,” a retired version of the school’s Joe Mountie the Mountaineer mascot, grinning up from the pavement. Though the faux-Indian facepaint, the coonskin cap, and the rifle are more reminiscent of the Indian mascots and caricatures of 1964-1965, now mostly phased out around collegiate sports, the mosaic still catches the eye, and probably has a Sheets Studio connection (if more likely to be student work than the Studio itself.)

Sue Hertel, “The Water and The Lion,” mural detail, Mt. San Antonio College, Walnut, c. 1965 (from Hall and Pietzsch, comp., 1996)

But the clear Sheets Studio (and friend-of-Sheets Studio) work for Mt. SAC was (is?) the set of library murals created by Susan Hertel and Tom Van Sant. According to the 1996 Mt. SAC history, Van Sant created murals symbolizing the social sciences and humanities; Hertel’s showed physical and biological sciences, with The Bull, The Flowering Tree, The Horse, and (as seen here) The Water and the Lion. From this photograph — all I have seen of the work — it is clearly linked stylistically to the wood panels and mosaic work of the Sheets Studio for Home Savings, especially (at this moment) reminding me of Pomona and Arcadia.

But where are the murals? If on wood panels, they could easily have been removed; canvas murals from the Sheets Studio can also be rolled up. Are they in storage? Covered? Egad, destroyed? I wish we knew more. (I asked around the library in June, but haven’t heard anything.) I hope these murals can be placed back in the public view, ideally at Mt. SAC art gallery or in a public, secure place nearby.

Please be in touch if you know more about these works!

Previewing Home Savings with American Trust: The Pageant of History and The Panorama of Today in Northern California

Millard Sheets, The Pageant of History in Northern California, for American Trust Company of San Francisco, 1954

In historical research, the most important sources often come to you incomplete.

So it seems with these remarkable images, done as a lithograph to celebrate the centennial of the American Trust Company, which was founded in 1854 as the San Francisco Accumulating Fund Association by Ephraim Willard Burr, who went on to be mayor of San Francisco. The company, which once owned a lot of northern California land, merged into Wells Fargo in 1960. The company president, James K. Lochead, was proud to introduce them as commissions from Millard Sheets, “himself a Californian.”

I first saw these prints at the UCLA Special Collections, and then I was fortunate to find copies for sale from Alan Wofsy Fine Arts; Alan also has the 4-page brochure where Sheets explained the images in detail (six paragraphs per image, like a long version of what the Van Ness branch has) and concludes this was where “the past becomes legend and the present, soon to be legend, begins.”

The images tell the history of the greater San Francisco Bay area, and they are a remarkable preview of what will appear in Home Savings images later: vaqueros and missions; wagon trains and railroads; women at the beach and sailboats out at sea; eagles and skunks and deer and lots of cows and horses. There are also other historical scenes that do not appear later: Fort Ross; the takeover of Monterey and the establishment of the Bear Flag Republic; the Ferry Building; the UC Berkeley Campanile; the Capitol building; large airplanes crossing the bay and grain elevators on the landscape. The farm equipment and industrial agriculture buildings likely reflected some of American Trust’s customers; the proliferation of American and Californian flags makes one wonder why these did not play a larger role in the later Home Savings works.

The American Trust and Savings branch at 10th and L in Sacramento once had three painted panels by Sheets — were these of the same them, or different? And who created the design for these works, and how did they relate to the Home Savings commission, the same year, which moved from a general and abstract history of finance and California life to the kind of specific history you see here?

I have tried the Sheets Archives without much information, and the Wells Fargo history center without getting a response; ideas and tips welcomed! I do think these remarkable prints hold a key window into the choice of historical scenes for the Home Savings buildings.

Millard Sheets Week: Hiding in Plain Sight at Manchester and Sepulveda

Albert Stewart, Bill Megaw and Millard Sheets Studio, “Horse and Man” sculpture for United Savings Bank, Manchester and Sepulveda, 1957

Hello! Curbed LA has been posting great materials for their Millard Sheets Week, drawing on this blog, the L.A. Conservancy tour last March, and their reporting. Great stuff, and welcome to their readers!

I am back to teaching at UTEP and so back and forth from LAX a bunch again. And so I have had occasion to visit this Millard Sheets Studio sculpture, originally commissioned for United Financial (or Imperial Bank — see below), and to observe it odd bedfellows on the corner of Manchester and Sepulveda.

From the Sheets Papers, it seems the sculpture is of marble, and is credited to Bill Megaw. (UPDATE: The commission is listed in the Albert Stewart memorial volume as “Horse and Man,” 1957.) It reflects, to me, the pose in George Caleb Bingham’s Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers through the Cumberland Gap and some pioneer sculptures around the country, as well as Lawrence Tenney Stevens’s Monument to Young Farmers which I just saw again, along with Tony Sheets and his wonderful exhibit at the L.A. County Fair. According to the correspondence from 1975 between Sheets and Kenneth Childs, once a Home Savings executive, it is marble, and by Bill Megaw. BGuilt for United Savings Bank, there was an effort to move it for Imperial Bank. Clearly, it stayed in place!

It is also a reminder of how many projects the Sheets Studio did. S. David Underwood, the subject of some upcoming posts, was the primary Sheets Studio architect, and with Rufus Turner and others they worked on Home Savings, but also on interiors, remodels, and other buildings that sometimes showed the same style–and sometimes were completely different. In the “definitive list,” which needs updating, there are lots of occasions where the Sheets Studio did a mosaic, or ordered furniture, or something, and so many traces of their influence on Mid-Century Modern art and architecture hiding around town–or already lost.

More examples in the weeks to come, but just one here: late in life, Millard Sheets provided a video oral history for Home Savings at his home in Gualala, taped by a time led by George Underwood. In that account, he mentions that Howard Ahmanson contacted him about the Home Savings work after seeing a March 22, 1953, article in the L.A. Times about Sheets’s work for Pacific Clay Products, at 4th and Bixel, which helps date their collaboration. The building is now the offices of the Children’s Home Society of California, and I don’t think the interior or exterior show influence of Sheets’s work — if so, let me know! — but it did launch a legendary partnership. And that is the most prominent of the ways the Sheets Studio work is hiding all around us.

Late Summer Dreams of San Diego Fun

I know I have posted these mosaics before, in regard to dating and process… but classes have begun at UTEP this week. So, while I have some longer posts in the works and research questions out there, I just wanted to revisit another “home” branch for me, in San Diego — as I look forward to being there Labor Day weekend and checking on the status of the mosaics, sculpture, and paintings.

These families look a bit solemn for the fun they should be having, but they are clearly enjoying timeless San Diego pastimes, from the animals at the San Diego Zoo petting paddock to the sights of California Tower, and an old tram that looks a lot like the current San Diego trolley system in its red trim. (No more elephant rides at the zoo — they stopped those decades ago — but I think the LA County Fair might offer that along with the Sheets Center for the Arts mentioned last week.)

Sue Hertel and Millard Sheets Studio, “The Harbor,” Mission Bay Drive at Garnet, San Diego, c. 1975-1977

Here, sailboats in the harbor compete with gulls diving after bread crumbs, the orcas of Sea World frolic on the left while fish and other creatures hang out in the tidepools at the right. Up the middle, the lighthouse of Cabrillo National Monument and the “world’s oldest active sailing ship,” the Star of India, highlight the centuries of European exploration and presence in the land of the Kumeyaay, but they wear their history lightly–the way I often found it, growing up in town, and the way many Home Savings art depicts it–just enough to make the local feel the bank belongs here, celebrating your home.

More from San Diego and beyond in the weeks ahead — for now, grasp the last summer you can! The Star of India even has visitors this weekend for the Festival of Sail.

Home Savings in Columbus, Ohio: Marlo Bartels’s Ceramic Tile Mosaic Saved

Marlo Bartels, ceramic tile mosaic for Columbus, Ohio, Home Savings, 1988; as photographed in Gail Paris Discovery Garden, Clinton Elementary School, by Terry Miller, courtesy Shirley Hyatt

One of the fun summer activities here in southern California is the Festival of the Arts / Pageant of the Masters bonanza in Laguna Beach. I went as a child (and have seen it since copied on Gilmore Girls), but this year I had a chance to return thanks to spending a few days in the studio and around town with Marlo Bartels.

As we have discussed, a number of artists were given Home Savings commissions in the final years of the art program, beyond just the Sheets Studio. Many of these locations are outside California, and often the local community does not know they are part of a larger series — hence they are even more threatened with destruction.

Marlo Bartels creates wonderful ceramic tiles by hand, shaping grooves and choosing glazes, and then matching bright colors and themes to the local landscape, whether it is a set of steps down to the beach in Laguna (replete with sea shapes and colors; see left) or creating artwork for corporate clients such as the Chart House restaurants and Home Savings. (Bartels also created the art for the wonderful Cancer Survivors’ Park in San Diego, my hometown, and has numerous residential and public commissions, as his website explains.)

Bartels’s work in Woodland Hills is threatened; I wonder whether his work for Home Savings in Thousand Oaks, Palm Desert (with Eric Johnson) and Monterey Park (with Astrid Preston); Pembroke Pines and Dunedin, Florida are associated much with his name or Home Savings.

The large image you see above is of Marlo Bartels’s mosaic for Columbus, Ohio, in 1988; a mosaic by Denis O’Connor and Sue Hertel at 6280 Sawmill Road, in Dublin, Ohio, in 1990, is gone, showing how quickly these bank buildings, no longer built for permanence, can disappear.

But the story of Marlo’s Columbus mosaic has a happy ending. As you can see, Marlo’s materials may be different, but he followed a rather standard Home Savings way of creating branch artwork — visit the city, look for something distinctive (the skyline), use local symbols and icons (Ohio state flag; state bird; local animals; shapes that echo those of the Moundbuilder peoples) and then put them into a permanent, colorfast material, such as ceramic, and hope to celebrate the community forever.

Marlo Bartels, Columbus mosaic ready for transport, 1992. Restoration was necessary in part due to vandals knocking over the transport. Image courtesy Marlo Bartels.

But in 1992, just four years after installation, the bank building was torn down (UPDATE: after it and the Graceland Shopping Center it was in were damaged in a fire) and the mosaic was threatened. Thankfully, the Casto Corporation (owner of the shopping center) was willing to help save the necessary wall, and Susan Gaunce of the local Clintonville Area Commission contacted Marlo and brought him to Columbus to help with the reinstallation and teach a few workshops. The mural then became the backdrop for the Gail Paris Discovery Garden at Clinton Elementary School.

I have just heard from Shirley Hyatt, author of Clintonville and Beechwood, that Clinton had been closed for renovations, but when it opened for this school year — this week!–the tile mosaic is to be brought inside, so the kids can see and touch it more often–and where it can be protected, hopefully for decades to come.

Thanks for Terry Miller and Shirley Hyatt for providing this image (and the updates). More of the move, the restoration work, or Marlo’s sessions in Columbus–or any of the outside-California locations–always welcomed!