Martha Menke Underwood Dies: Pomona Valley Artist and Crucial Home Savings Mosaics Link

Martha Menke Underwood

I was sad to learn that Martha Menke Underwood died on February 15, 2012. I had the chance to visit her in November 2010, on a day she was at work in her painting studio; like so many of the Pomona Valley artists with whom Millard Sheets collaborated, she had achieved renown in a number of media, before, during, and long after her time working for the Sheets Studio. She was especially known for her tapestries and other “stitchery” works.

Martha had studied with Jean and Arthur Ames; Arthur had overseen her master’s thesis, and shared an interest in the revival of tapestries as a fine-art form. After graduating from Scripps and Otis, Martha was briefly employed by Wallis-Wiley Stained Glass (the contractor the Sheets Studio used as well) before working directly for Sheets. Some of her tapestries hung in the first major Sheets bank commission, for Mercantile National Bank in Dallas; she also became essential to the design, installation, and construction of the early Home Savings mosaics.

Martha left the Sheets Studio soon after she was married, to the Sheets Studio architect S. David Underwood, in around 1960; they later divorced. But, in those busy years, Martha Menke Underwood was instrumental to the creation of the Sheets Studio style of mosaic work.

Though mosaics were essential to the new look of art and architecture that Millard Sheets was providing for Howard Ahmanson beginning in 1954, Sheets and those around him had no expertise in how to create them. Initally, the mosaics were designed in the Sheets Studio but sent to Italy or, Martha said, to Mexico for fabrication, but Sheets grew frustrated with a process out of his control, sending back versions of his designs stylized against his wishes.

According to Martha’s account, she was tasked with figuring out the process. After more frustration with imported mosaics–she specifically remembered having to piece together the outline for the Arcadia Home Savings and Loan mosaics on the spot, as the concrete backing for the installation waited–she took charge of ordering smalti and creating a tile-cutting and -setting procedure in the Sheets Studio.

Martha Menke Underwood tapestry behind freestanding Sheets Studio mosaic, Mercantile National Bank Building, Dallas, 1959

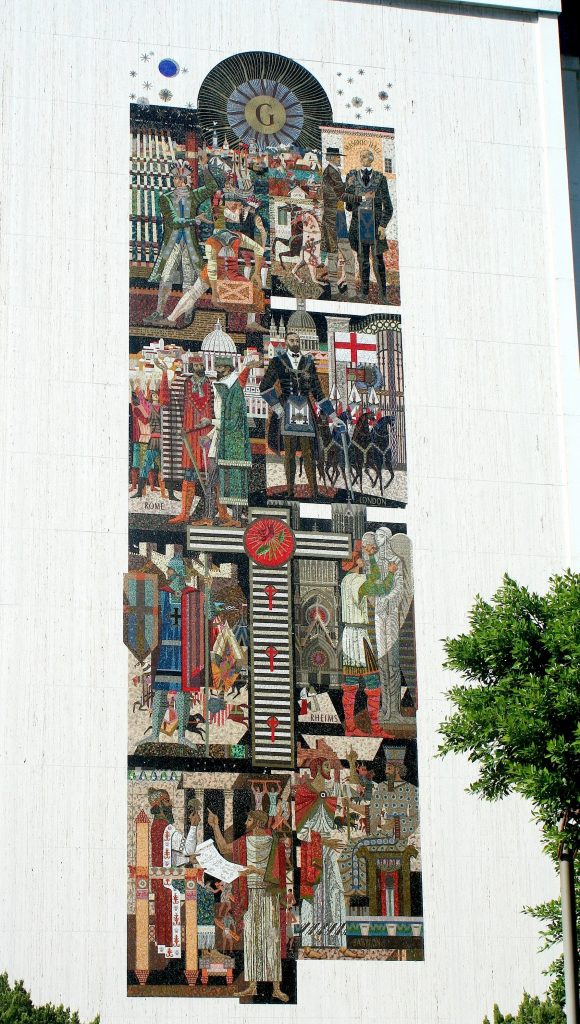

Martha remembered how exhilarating but stressful work for the Sheets Studio could be. As the timing for completion of the Los Angeles Scottish Rite Masonic Temple mosaics was tight, various sections of the four-story-tall exterior mosaic were taken for installation before she could be sure the colors and lines could match up. But I think the resulting mosaic (below) demonstrates how it worked out!

Finally, Martha decided to hire an artist who would take over the details of the mosaic operation, from ordering to installation. Her search led to the Studio’s master of mosaic fabrication, Denis O’Connor, whom Martha helped to train. Martha continued working for the Studio, part-time, and contributed to the iconic mosaics at Sunset and Vine, the Garrison Theater, and Notre Dame, among other projects.

Martha Menke Underwood followed the pattern of many Pomona Valley artists in finding the time working for Millard Sheets as invigorating but ultimately distracting from her own art interests. She credited Millard Sheets with arranging for her large-scale tapestries to be woven at the historic looms in Aubisson, France, and she stayed close to many of her fellow artists; she also taught art for 27 years at Chaffey College..

Her website holds many of her last works, as well as a picture with a wide smile, much like the one that welcomed me. She will be missed.

Steve Rogers at Sherman Oaks: Home Savings Art after the Millard Sheets Studio

It is great that the Millard Sheets Papers and the Denis O’Connor Papers have been donated to archives.They provide a tremendous amount of detail about the art and architecture of Home Savings, starting in 1954. There, the work of the Sheets Studio team is documented — a changing cast including these two men; their main collaborator Susan Lautmann Hertel; architects S. David Underwood, Rufus Turner, Robert Kurtz, Robert Nilson, Milton Holmes, F. Arthur Jessup, and Francis Lis, and Frank Homolka and Jess Gilkerson of Long Beach; contracted sculptors such as John Edward Svenson, Betty Davenport Ford, Albert Stewart, Renzo Fenci, and Paul Manship; John Wallis and Associates for stained glass fabrication; other Pomona Valley artists such as Arthur and Jean Ames, Martha Menke Underwood, Melvin Wood, and Sam Maloof; studio regulars including Nancy Colbath, Alba Cisneros, Brian Worley, and Jude Freeman. More than 200 projects are documented in this way (though the records remain incomplete, as described here).

But then there are at least 14 other Home Savings buildings with art and architecture to consider. Starting in 1989, Home Savings (then expanding as Savings of America into Florida, New York, and other states) decided to cut ties with Denis O’Connor and Sue Hertel, for reasons I have not quite figured out yet. At first, Home Savings fine arts coordinator Kristen Paulson added artists such as Steve Rogers, Richard Haas, Roger Nelson, Marlo Bartels and Astrid Preston, and in the final few years of commissions, these artists replaced O’Connor, Hertel, and the Sheets Studio method.

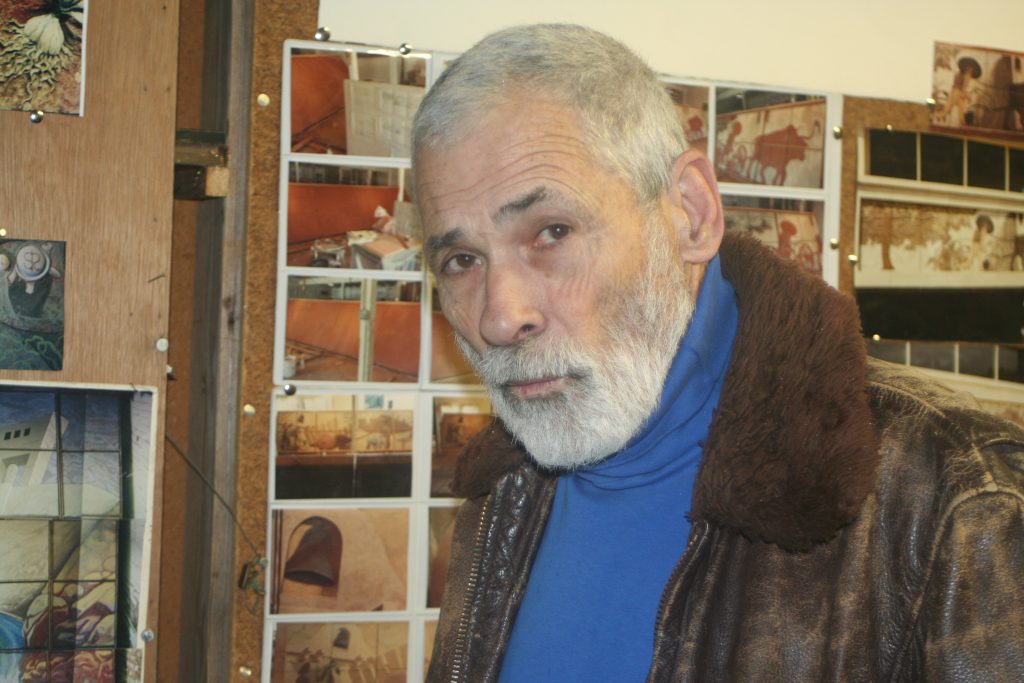

Why? Was it cost? Theses final works are mostly painted flat-tile artworks, still painstaking but less expensive than the traditional Sheets Studio mosaic. I am seeking out these artists to learn more, and I had the pleasure last month of interviewing Steve Rogers.

Steve first gained attention for his bas-relief panels of boxing scenes; in 1989, he received the Home Savings commission, and afterwards did a marvelous scene in the lobby of the Los Angeles Metropolitan Water District, the relief on the tiles jutting forward with the rush of the water. He has been recently working on fantastical images of chickens, showing the same energy and attention to bright colors and contrasts that his earlier work has shown.

Speaking with Steve Rogers and seeing his notes and files from the Home Savings commission, I was struck by how similar the process remained from the earliest works: choosing a theme that reflected local history or community; input from the artist and the bank representatives on themes and edits to make; and then the logistics of fabrication, engineering, and construction to get the image ready for permanent display along a busy street, over the door in earthquake country.

From the street (as we saw on the Autry bus tour of the Valley Home Savings sites), it looks easy, and simple: those images of Day Begins and Day Ends (titles the artworks should have but that are not on the pieces, another characteristic omission) at the local mission, the carreta out front, the man hard at work.

But, from the files, you can see the negotiations, the short time frames, the worries and contract provisions that went into making this art. From Steve, I got the same sense of what I can find in these files: this work was exhilarating, but the uncertainty could also be unnerving — Would it be done in time? Will I make any profit? Will there be another commission? Steve’s work shows the same knack for crystallizing the sentiment of the community, but unfortunately, he has not been chosen for similar projects after the Metropolitan Water District.

I am in touch with more of these artists, and I welcome contact from even more artists, and their bank liaisons. I look forward to sharing more of the stories from the oral histories on the blog and in the eventual book.

Redwood City, Menlo Park, and Other Mysteries of the Sheets Studio archives

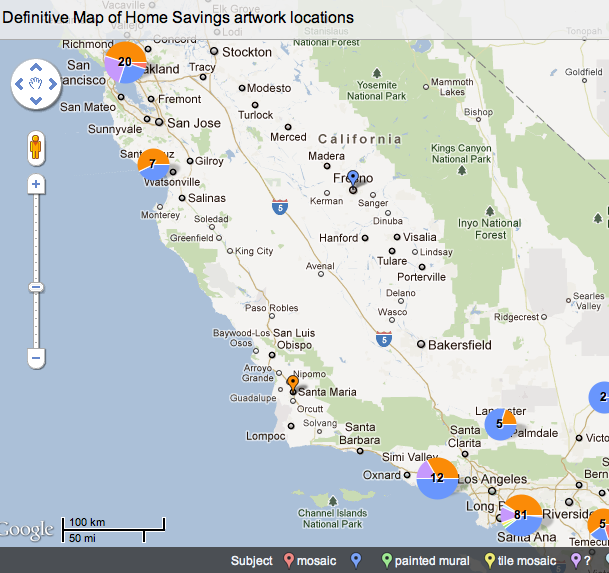

The responses to the “definitive list” have been great! I know the spreadsheet section is a bit hard to read, but the interactivity of the map provides a nice perspective on the scope of the project. I will integrate corrections, updates, and even clean up the map data in the weeks ahead. I even had a chance to see a 1992 Home Savings directory, so I can get a lot of the missing addresses.

But the addresses and the maps can’t do everything — and neither can the archives. As I may have mentioned, the Millard Sheets Papers and the Denis O’Connor Collection are spectacular resources for the workings of the studio, the names of those artists involved with each project, the costs and the timeline. But the paper record often peters out, and it can be unclear whether the project was suspended, canceled, finished by someone else, or simply completed without incident.

Google StreetView can provide some knowledge about what is there on the outside now, and historic photographs, when available, provide great evidence of what was there. But often all we have is memories about what was there — and so I ask again for your help with those memories.

The Redwood City branch provides a case in point. I visited Redwood City in the spring, on a swing through the Peninsula branches (more for the website, one of these days). The building was a Home Savings, it was clearly designed by Frank Homolka, and Update: This seems to have been a Guaranty Savings and Loan, a northern California bank chain once controlled by Howard Ahmanson, until 1958. It seems to have had a Sheets painted mural over the teller windows. I asked a manager about it, and he said it had been painted over — seemingly another case, like the West Portal mural, of Sheets Studio artwork being lost.

But — in the archives there is a discussion of a “Redwood City” branch at 650 Santa Cruz Avenue in Menlo Park, and an order for two pumas from sculptor Betty Davenport Ford. I visited that location, and didn’t see evidence of those pumas either — but it is possible they, too, were never installed.

So, do Redwood City and Menlo Park have two cases of missing Sheets Studio art, or (as I suspect) was there never a mural there to paint over? Only those of you who have lived near this branch and banked there before 1998 can let me know for sure. The archives and the current visits can only get us so far.

A “Definitive” Map of Home Savings Locations and other Sheets Studio Work

See the current “definitive list” here — and the interactive, scalable map of the locations (with some somewhat misleading information on which artwork is where) here. Map courtesy of BatchGeo.

Well, I have finally done it. About two years after I discovered I was working with hundreds, not dozens, of sites, I finally have something like a definitive list of the 138 Home Savings / Savings of America sites with artwork ready. This is thanks to the archival Sheets Papers and Denis O’Connor (DOC) Papers, and the notes in those files from Sue Hertel (SLH in my code) — and a lot of hard work from volunteer (and former Home Savings employee) Teresa Fernandez, and the magic of Google StreetView.

It is not perfect — and I need your help to send in corrections. Send in correct addresses, send in new status updates, send in alerts of places you think are threatened. I have found that the California Art Preservation Act is included in many of these contracts between artists and Home Savings — even when the artwork was in, say, Florida — so there is a mechanism to help with their preservation.

This is an imperfect simplification of my main work database, which holds the names of each artist who worked on each piece, archival notes, construction dates vs. completion dates, and more. But I do hope that it leads to a lot more information about the current state of this artwork coming to light!

Home Savings, LACMA, and the mausoleum?

A few final thoughts from researching the Pacific Standard time exhibits and the Sheets Studio:

First, the LA Conservancy has a Pacific Standard Time tour of Millard Sheets sites in Claremont and Pomona on March 18. A great time to see these connections; sign-up info here. Stay late in the day, and I should be on hand as well for a panel discussion.

Second, have you ever noticed how the Ahmanson building at the LACMA looks a lot like the early Home Savings buildings? Howard Ahmanson clearly had his favorite architects — Edward Durrell Stone, William Pereira, and Millard Sheets’s Studio — and it seems the museum building borrows from the Home Savings look — blank travertine faces with no windows, lower entrance ways, into soaring central spaces. Instead of teller windows and interior mosaic, you get more blank faces in the Ahmanson building atrium, hiding the floors of art behind.

This element of the Home Savings architecture was derided as looking like a mausoleum — perhaps that is part of what motivated Ed Ruscha to dream of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Fire.

Ed Ruscha, Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Fire, 1965-1968

*

I have been busy with research at the Huntington, more oral histories, and new initiatives — including a definitive list of locations — to be highlighted here soon. Stay tuned!

Missing Millard Sheets: Pacific Standard Time and the Art of Home Savings

Dora De Larios, Franciscan 400 Series Contours CV Tile, 1963-1964, as installed by the Millard Sheets Studio at Pomona First Federal, Claremont

Pacific Standard Time is a juggernaut: over 60 exhibits in five Southern California counties, documenting and explaining — in many cases, for the first time — the role of the L.A. art scene on the world stage. The Getty has provided the bold vision (and the financing!) to create this massive multi-exhibit conversation, and the Performance and Public Art festival section of the shows, running from January 19 to 29, will only add to the marvel (and overwhelmingness) of it all.

Pacific Standard Time has included many overlooked artists, overlooked art forms, overlooked themes, and overlooked art. And what was included reflected what the participating art organizations wanted to highlight. But the fleeting presence of Millard Sheets in the Pacific Standard Time shows demonstrates some of the art-world boundaries that remain.

First, disclaimers: I know I am letting the myopia of my Home Savings project drive this post. I know that Sheets was already a nationally known artist before 1945. And I will get to the three Pacific Standard Time shows that include Sheets below.

But if the Pacific Standard Time exhibits would have commissioned an art-world treaty painting like the one showing Paris ceding to New York, Millard Sheets would have clearly been a face in the crowd, given not only his prominence among the California watercolor painters but his role as Director of Fine Arts at the LA County Fair 1930-1955, teaching at Scripps College 1931-1954, director of the Otis Art Institute after 1953, and his role advising Howard Ahmanson as he shepherded the Los Angeles County Museum of Art into being, and Sheets’s later role in curating the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation collections, now a permanent part of the Huntington collections. Perhaps Sheets’s influence is too large and too disparate to measure easily.

As this blog and the associated research project suggest, Sheets’s most important art contribution to LA after 1945 was the art and architecture of the Home Savings banks. Sheets managed a studio full of artists and architects to turn initial sketches and an open-ended offer from Howard Ahmanson into landmarks of the local community, telling history and celebrating family life through very traditional art forms: mosaic; conventional figurative paintings; stained glass; sculpture. In no way avant-garde, done for a commercial patron to advertise their business, it is easy to understand why the Pacific Standard Time exhibits (and other standard art-history studies) have missed the importance of these Home Savings works for the landscape of postwar southern California (and beyond).

But — there are elements of this story in four of the Pacific Standard Time exhibits. In order of increasing relevance, I give you:

4) California Design, 1930-1965: “Living in a Modern Way” at LACMA. This is the marquee decorative-arts and design exhibit for Pacific Standard Time, and it delivers — everything from an Airstream trailer to the reconstruction of Charles and Ray Eames’s living room in the gallery. There are the perfect exemplars that match the white-walled modernist setting — for example, a Japanese-style screen painted by Millard Sheets — but also lots of helpful contextual information on the source of inspirations, the choice of design media, the marketing and distribution of these products, often intended for the home or daily use. Items from Sheets’ influential 1954 Arts of Daily Living show are echoed here as well.

3) Common Ground: Ceramics in Southern California, 1945-1975 at the American Museum of Ceramic Art (AMOCA). This show uses Millard Sheets as an organizing principle–ceramicists with a “direct connection” to Sheets and “his dynamic personality, inspirational teaching, and business savvy” are included. The AMOCA’s new space has a spectacular Sheets and Hertel mural along one wall, and one part of the exhibit puts ceramic tiles used by the Sheets Studio (like those above) into their original context, in an artist-in-industry program Millard Sheets established with Franciscan Ceramics, including the work of Dora De Larios, and which led him to do some large-scale ceramic-tile mosaics with Interpace. And its exhibit book has the most up-to-date scholarship on Millard Sheets’ role as interface between business and industry, with essays by Hal Nelson and others that will be a spectacular resource for me.

Dora De Larios’ work was also included in the Autry’s Pacific Standard Time exhibit, part of the L.A. Xicano subset of PST. Race and memory, nostalgia and the growing multiculturalism of postwar southern California is key to how I situate the Home Savings artwork, so I found

2) Sandra De La Loza’s Mural Remix installations at LACMA very powerful. I particularly like the video installation where naked men and women paint the murals onto themselves (through some green-screen magic), demonstrating some of the ways in which the murals become a part of us — something that I think is true of the Home Savings work as well. The more standard video documentary — catching up with Judy Baca and other 1970s Chicano muralists in LA — has lots of great info as well. There is also an affiliated tour with Sandra on Saturday January 21.

1) The House That Sam Built: Sam Maloof and Art in the Pomona Valley, 1945–1985 at the Huntington Library. If I have to pick a #1 exhibit for understanding the Home Savings artwork and the Sheets Studio work, this is it. The LACMA has the Eames’ living room, but this exhibit, curated by Hal Nelson, feels like Sheets’s living room, with a collection of his POmona Valley colleagues from Sam Maloof to enamelists Arthur and Jean Ames to sculptors Betty Davenport Ford, John Edward Svenson, and Albert Stewart, Sheets’s constant collaborator, painter Sue Hertel, represented with work in their own style, but with hints at how Millard Sheets also used some of their talents in Home Savings buildings as well.

Am I missing something? Let me know in the comments. And read more about these exhibits and their ties to Sheets here, here, here, here, here, and here.

Welcome to 2012, and a Reinvigorated Blog!

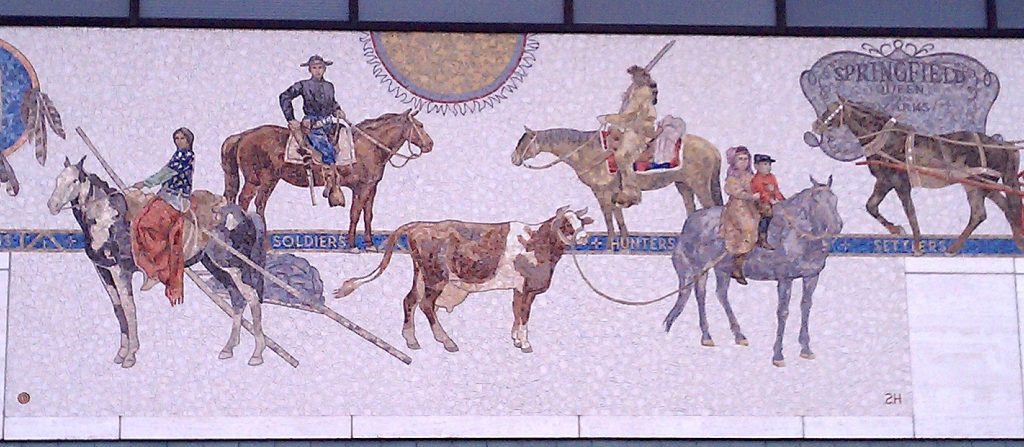

Denis O’Connor and Sue Hertel, mosaic, Savings of America, Springfield, Missouri, 1986. Note the goof at installation that reversed the SH of Sue’s signature at bottom right.

Hello!

After a semester on other projects, I am proud to announce that I am a Haynes Foundation Fellow at the Huntington Library this semester, so I am working full-time on the history and preservation of the art and artwork of the Home Savings and Loan buildings.

My plan is to complete research in the papers of Millard Sheets and Denis O’Connor, and to track down more interview subjects and other paper collections to help me complete the research. By fall, I will be writing, and hopefully we can see a beautiful book, with lots of color images of this remarkable artwork, appear in late 2013/early 2014. So any tips, leads, and memories are always welcomed!

In the “radio-silent” period, I have been to Home Savings locations in the Bay Area and around Los Angeles, to Savings of America locations in Missouri, and to all the presentations I mentioned in my last post. Also, thanks to a Jonathan Heritage Foundation fellowship at the Autry National Center over the summer, I have determined more about where the “Home Savings style” drew from, in the decoration and marketing of other Los Angeles banks in the early twentieth century, especially Security Trust and Savings (later Security First, later Security Pacific). More about all that soon.

I also am proud to announce one new publication and two more great events to put on your calendar:

This month, look for a (cover?) story — by me — in Huntington Frontiers, the magazine of the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, about the Home Savings and Loan artwork and the collections I am using.

Sunday, March 18, “Millard Sheets: A Legacy of Art and Architecture” in Pomona and Claremont, organized by the L.A. Conservancy’s Modernism Committee.

Sunday, May 6, a panel discussion (with me and noted architectural historian Alan Hess) at the gallery exhibition of Home Savings locations, organized by Cal State Fullerton students Concepción Rodriguez and Wendy Sherman, at the Grand Central Art Center.

I will now resume posting weekly. Next up: all the great Pacific Standard Time exhibits that show the circle of mutual influence around the Sheets Studio and the Home Savings work. Details to come, but if you want to get ahead, the key exhibits are The House That Sam Built at the Huntington Library; Common Ground at the American Museum of Ceramic Art (AMOCA — which has a spectacular Sheets and Hertel painting in its new location, a former Pomona First Federal); and California Design, 1930-1965: “Living in a Modern Way” at LACMA.

Happy 2012! I look forward to reinvigorating the conversation.

Home Savings Bank Art Upcoming Events

It’s September, so summer must be over. I’ll be back to posting here regularly soon, but I just wanted to put a few events on your Home Savings Bank Art calendar.

Sunday, October 23, 2011 — I will be leading a bus tour to some of the San Fernando Valley Home Savings sites, in conjunction with the Autry National Center’s Pacific Standard Time exhibit. Information on how to make a reservation here.

Saturday night, December 10, 2011 — I will be speaking about the Home Savings work in conjunction with the Pacific Standard Time exhibit at the American Museum of Ceramic Art in Pomona–newly relocated into a former Home Savings. More information about the exhibit here. UPDATE: My talk announced here.

May 5 – June 17, 2012 — Home Savings bank locations featured in a gallery show at the Grand Central Art Center, Cal State Fullerton, organized by Concepcíon Rodríguez and Wendy Sherman. I am helping them with the research and the exhibition catalog.

Stay tuned, and be in touch — more about summer discoveries of art threatened or destroyed in Pomona and Redwood City, and new images of lost work in Long Beach and Beverly Hills, to come!

Iconic but not Exclusive: Sheets Studio bank art and architecture

This week I have had a chance to catch up with some of my fellow scholars interested in the art and architecture of banks, whether in the human story of their creation and management or the architectural story of how technological innovation — from check processing to ATM cards — changed the physical shape of banks. It is nice to find such a community working on telling these overlooked stories!

One beautiful bank with its own set of surprises is the Pomona First Federal location at Indian Hill and Foothill, in Claremont. Driving by quickly, the bank has all the hallmarks of the Home Savings locations — the travertine, the mosaic, and atrium-like spaces enclosed by columns and facing the parking lot and a prominent corner. Inside there is a prominent painting of local history, much like at another former Pomona First Federal location (the new site for AMOCA).

Indeed, the lotus-like capitals seem unusual, but not out of the realm of the possible for Home Savings. And the bank’s (former) name is prominent in the artwork — not quite the Home Savings shield, but the same sort of permanent corporate marker, though one left in place here.

The records suggest these similarities are no coincidence, and they are not evidence that Sheets could only think in one mode. This was a rejected Home Savings design — a bank repurposed for the Claremont site from another location. The artwork seems to relate to the Pomona Valley — the interior image is a rich scene of Native Americans gathered in circles around wigwams and a horse corral, credited by many to Nancy Colbath despite the Sheets signature. So it seems likely Sheets simply borrowed an architectural design from a project Home Savings did not build, and then drew on his deep affection for his home community to quickly provide appropriate imagery.

But, looking back from our era of non-compete clauses, and for a project so linked to Home Savings’s image, it is remarkable that the Sheets Studio could do this work for Pomona First Federal and similar echoes in the work for Texas banks. Home Savings had not reached those communities, but as it expanded nationally, one wonders if these close copies ever became an issue.

It clearly was something that Pomona First Federal looked upon with pride, as a later renovation reveals. When PFF was ready to install a drive-up ATM station in 1982, they contacted Denis O’Connor, the Sheets Studio mosaicist who had done the tile work and contributed to the design of the original mosaics.

O’Connor provided a matching image — another Native American figure on a black-and-white horse, back turned toward the snowy mountain, again walking through the wonderful M.C. Escher-like leaves that evoke bird shapes above the desert plants. I assume it was satisfying to see such a commitment to continuity, when the experience of banking went from entering a temple to commerce and commercial relationships to the chance to grab your cash without getting out of the cash.

So much of what this art and architecture can offer is that sense of continuity–even as the bank names change. ( M. Danko has good images.)

*

This will be my last regular post for the summer; the academic year is winding down, so I will be traveling more, researching more, but not in a position to post easily every week.

I know I owe our faithful readership a definitive list of these banks, their addresses, dates of construction, and current status — I am working on it, and I welcome your input. I also hope to get more interviews done, with former Home Savings employees, and to seek out more resources. And I will provide a better index to this site, more than just keyword searching.

I will be back regularly on the blog in August, and with any great finds in the meantime. Do keep commenting and checking back, though, for more about these treasures.

If it is good enough for a Chase ad, is it good enough for a preservation commitment?

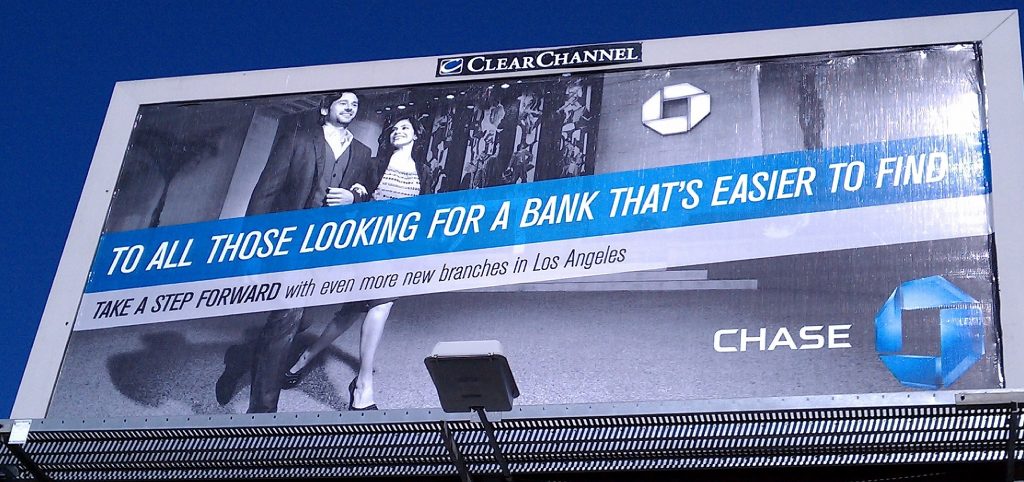

My wife is always warning me that it can be dangerous to let a historian drive — they see something evocative along the roadway, and they might forget about the rest of the cars. As I drove home along Pico this past Monday, I was surprised to find this new billboard on the north side of the street, between Curson and Fairfax. No worries–I got over safely, parked at a meter, and snapped a few photographs.

This ad apparently reflects a new Chase campaign, at least for the LA area. Given the ubiquity of Chase and its national-chain competitors, I assume the message of the ad is intended to suggest that you might be tempted by credit unions, community banks, and others with good press in this moment of fees and bailouts, and the rest, but at the end of the day, what you really want is a bank you can find anywhere, anytime — and that is what Chase and their competitors have bet on.

But, in the context of the Home Savings banks’ place in the LA landscape, I think the choice of the Sunset and Vine location as backdrop is telling. My larger history about these banks is not just to map their locations and advocate for their preservation, but also to consider why Howard Ahmanson figured it was a good investment for his Home Savings and Loan banks to be icons, ornate works of art on landmark corners throughout Los Angeles.

The choice of a former Home Savings for the ad is the first use of the Home Savings properties in a Chase ad (as far as I know–know of others?), and it suggests a second, deeper sense of “easy to find” –not just a bank that would come up on your GPS as nearby, but a bank location that sticks out in your mind, as the Home Savings locations do.

I have yet to hear a firm commitment from Chase that they want to be the best possible stewards of the Millard Sheets and Associates art and architecture. But if it is good enough to use in an ad, can’t it be good enough to commit to preserving? That could be truly good news.

*

By the way, I have also come across fans of what was on the location of Sunset and Vine before the Home Savings — the NBC radio studios, an Art Deco building with a large, expressive mural welcoming visitors–much as Millard Sheets would design for Home Savings. Great photos, from construction to demolition, here.

Given the 1964 demolition date, it seems the building was torn down just as Home Savings went in — a question of cause or coincidence I will be researching soon.