February turned out to be a busy time–so much to do, so few days to do it?–and the start of March offers no let-up. Most of the time I am happy with so busy–research, writing, conferences, commuting, teaching, grading, and that is just for work–and it beats having nothing to do, though that seems an impossibility nowadays.

But it has meant that I have not been out on the streets, tracking down Home Savings and Sheets Studio archives and statuses that much recently. At least spring break is coming soon.

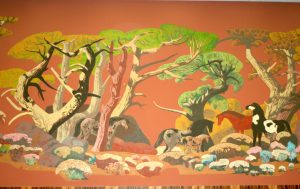

So, looking through my own Home Savings photo archives, I was struck today by the calm of this simple mixed-media tree with birds, completed by the Sheets Studio and affixed to the end of an office building in Claremont. (I think it it is on 4th, between Harvard and Yale avenues.) It seems a perfect image for spring.

Trees and birds seem to have been almost as important totems for Millard Sheets as horses; from his home in Gualala to numerous compositions in many media, the tree filled with the sights and presumably sounds of birds reflected a sense of contentment and joy that the Sheets Studio work exudes.

I assume this is an early piece, as the mosaic tiles are used merely as background, and the birds and tree is represented in three dimensional ceramics, some with colorful accents. What comes to mind are other earlier works — the sculptural birds and trees, as well as other animals, by Betty Davenport Ford, and the marvelous bull at the LA County Fair’s Millard Sheets Center for the Arts building, completed in 1952 by Albert Stewart and John Edward Svenson. Like the tapestries, they represent the efforts to use color and modernist lines to rethink traditional art forms, as Picasso, Miró, and others were doing in these same years.

This is at least as labor-intensive as the glass-tile mosaics, harder to install, and likely far more brittle, so harder to maintain. Nevertheless, this example has held up wonderfully–and likely adds a quick, upbeat note to all those who notice it, as they walk in the leafy, sunlit streets of Claremont.