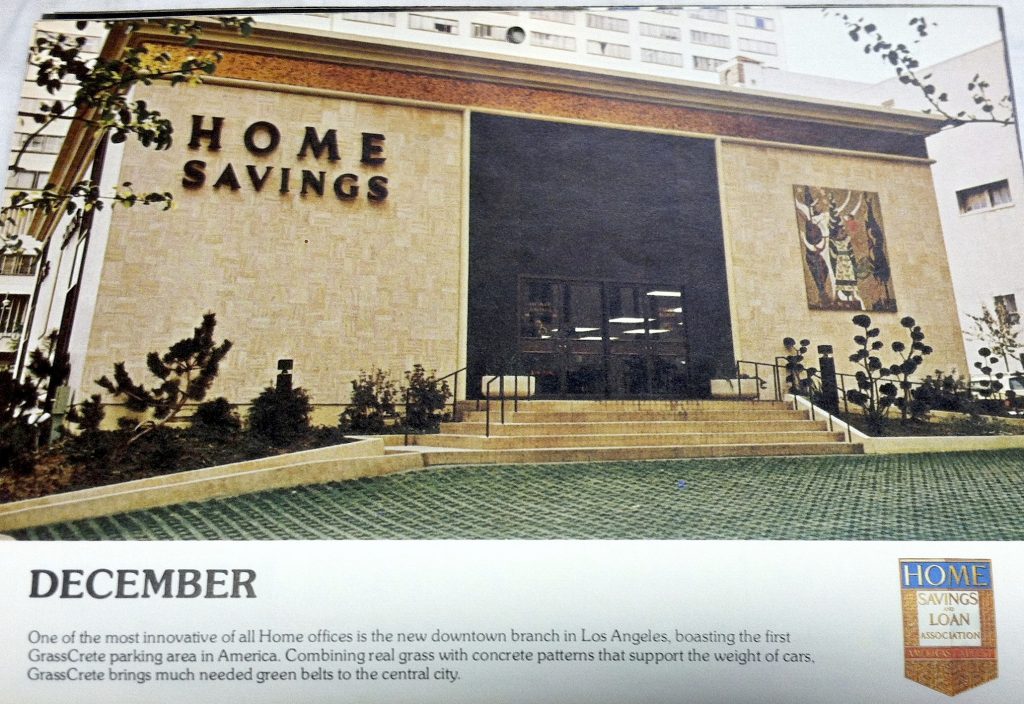

Millard Sheets, National American Fire Insurance, 3731 Wilshire, 1954 (demolished). For sale at Art-Books.com, Alan Wofsy

Eric Abrahamson’s new book, Building Home, describes the first interactions between Millard Sheets and Howard Ahmanson, and says some about the National American Fire Insurance building. It is crucially important but hard to document, since its demolition in the process of the construction of the Ahmanson Center.

The images you see here come from the remarkable collection of mostly color sketches for sale via Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, in San Francisco; these and more appear on their website, with prices and other details. But my work in the Ravenna Mosaic Company papers have provided more insights about their fabrication and installation.

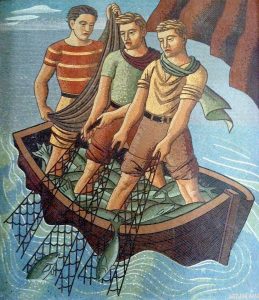

Millard Sheets, Firemen at Work sketch, for Ravenna Mosaic Company fabrication, 1954. For sale at Art-Books.com, Alan Wofsy

In the early 1950s, Sheets and the Ravenna Mosaic Company did work for Mike Lyman’s restaurant (unclear which one — they were once at 424 W. 6th St, on Pershing Square according to designs in the Library of Congress Winold Reiss collection; and 1627 North Vine in Hollywood and Hill at 8th downtown, according to this matchbook or Mike Lyman’s flight deck at the airport, in this old footage— all now demolished) as well as the Precious Blood church in Los Angeles. They also discuss a General Insurance building mosaic on Wilshire — which may have been for the building at Wilshire and La Brea by that name — but if so, it is gone too.

What we do have, however, is discussion of “the Firemen’s Panel” that the Ravenna Mosaic Company had done for Sheets–and the installation diagrams.

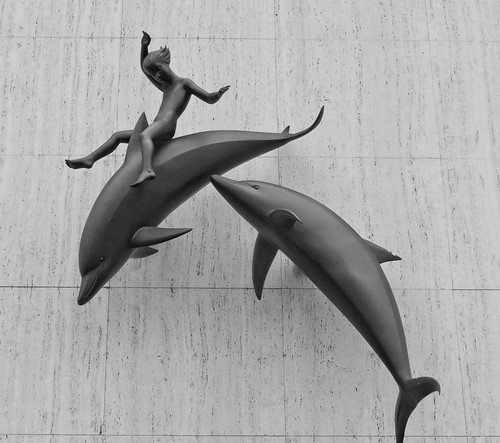

The mosaics were of course to large (and too heavy) to ship all put together, so the practice was always to create segments of the mosaic–normally pasted, face first, onto paper–and then stack and ship them to the installation site. (As we have mentioned here, you have to be careful to keep them safe from water as well as infestations, lest the paste be eaten and the design destroyed.)

And so, in order to get the installation correct, you needed a map of the mosaic, matching the pieces back into the correct order. They existed for every installation, but they were mostly destroyed — but it just so happens that the Ravenna Mosaic Company kept a copy, when they sent another to Sheets for installation.

![Ravenna Mosaic Company, General [National American] Fire Insurance Building, Los Angeles, 1954-1955, courtesy of Saint Louis University Libraries Special Collections. Special thanks to John Waide.](http://test.adamarenson.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Ravenna-SLU-Natl-American-Fire-Insurance-layout-cropped-1024x660.jpg)

Ravenna Mosaic Company, General [National American] Fire Insurance Building, Los Angeles, 1954-1955, courtesy of Saint Louis University Libraries Special Collections. Special thanks to John Waide.