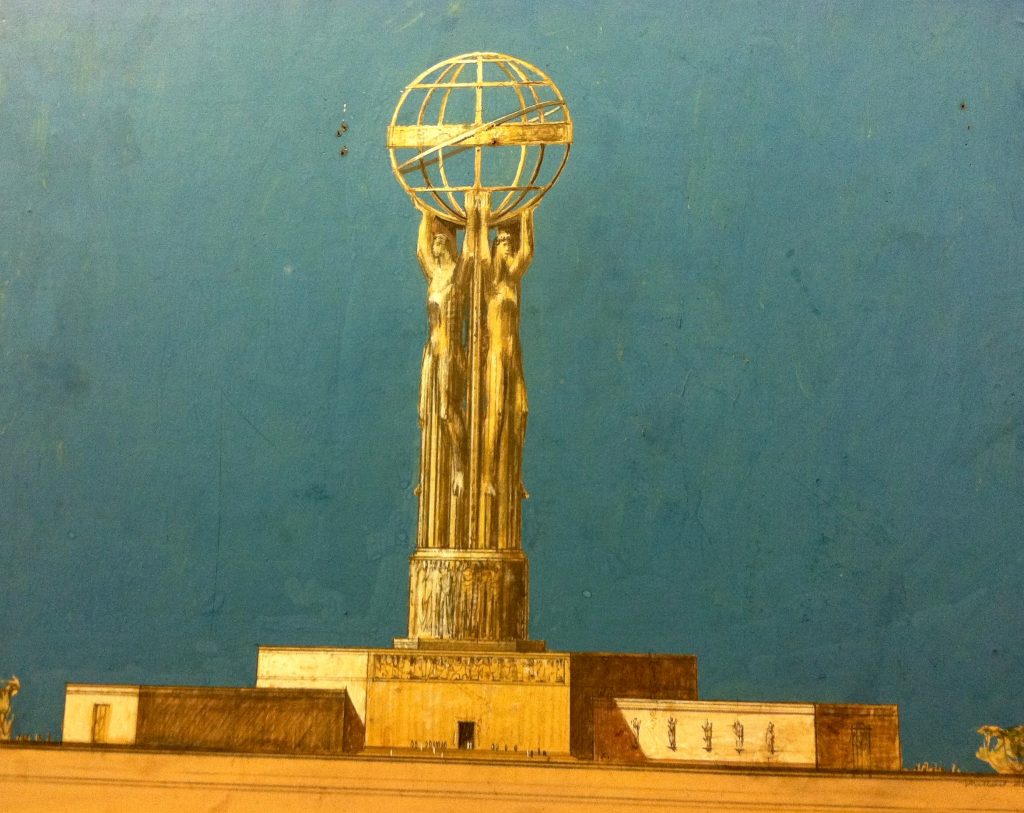

Richard Haas, sketch for Forest Hills branch, Savings of America, 1988-1989. My crooked image with permission of Richard Haas.

Over the past week I was far from Southern California, the part of the country most associated with Home Savings & Loan, in New York City.

Yet Home Savings (under the name Savings of America) expanded into New York, Illinois, Florida, Missouri, Ohio, and Texas in the 1980s and 1990s. The company worked to keep its brand assets in play there, with distinguished customer service but also distinctive buildings, with artwork that reflected the community. From the Denis O’Connor Papers, I have found some interesting conflicts between the local historical societies in these states and Home Savings, perceived as an outsider corporation. But the artwork did get done and installed in many of these locations.

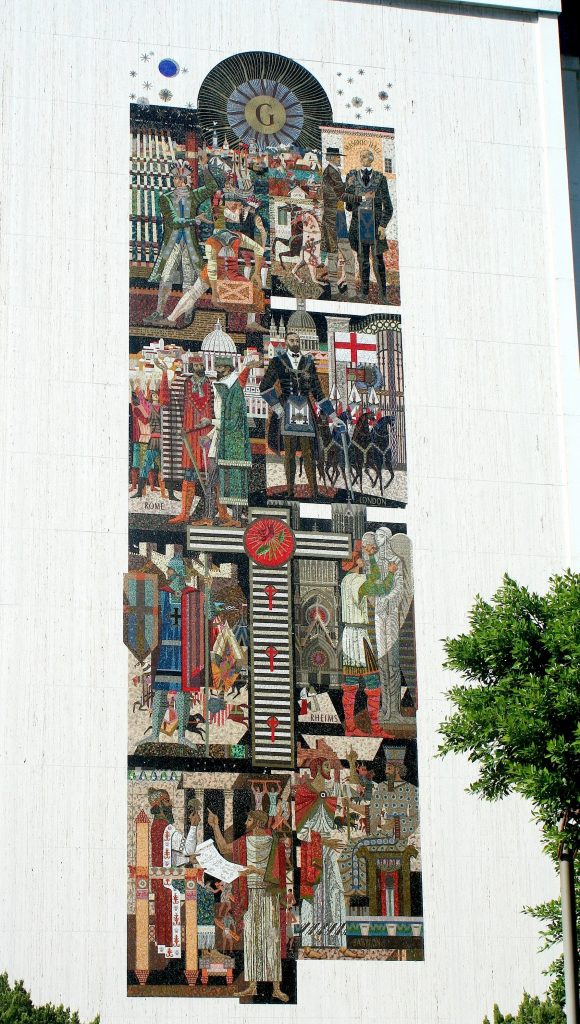

There is one mosaic on a former New York Home Savings, in Forest Hills, at 108-36 Queens Blvd. It is by Richard Haas, an artist still active in New York City, who I had the pleasure of interviewing on my trip. Haas completed commissions for the 7th and Figueroa and Pasadena towers in Los Angeles, the Irwindale headquarters (all paintings) and designed mosaics for many of the Florida locations, with the mosaic fabrication done in Spilimbergo, in northeastern Italy. (He told me quite a story about the mural designed for Naples, Florida, that never got installed — the project was delayed, and the mosaic, all pasted to sheets, was put in storage. When they opened up the storage room to get the mosaics, they just found mounds of tiles — the industrious Florida insects had eaten the sugar paste off the paper, and destroyed the mosaic.)

Haas’s New York mosaic shows the Manhattan skyline in the distance, with the World Trade Center towers prominent; in between, the tracts of housing, tree-line streets, and larger developments create a patchwork. In a sign we are no longer in car-loving California, the bottom of the image is anchored by the historic Tudor-influenced train station nearby, for the Long Island Rail Road. Haas, a visual artist productively obsessed with the wonders of architecture, added house portraits of other local architectural gems to the upper corners, in the multi-view manner of 19th-century cityscapes.

Haas’s mosaic was installed on the curving facade of the Forest Hills Savings of America branch (shown here as a Commerce Bancorp branch, in 2007, before that bank’s merger). While, like so many Home Savings locations, this is a prominent corner, I am unaware of any other branches that have curving facades, instead of other approaches to the corner lot. The curve makes it hard to take in the full image as installed, so it is nice to have my rough photograph of the color drawing, above.

Haas’s work demonstrates how the Home Savings motif could translate to new locales such as New York. But this was the only mosaic completed for New York. Come back next week to learn about how some of the same themes were expressed in a different medium.