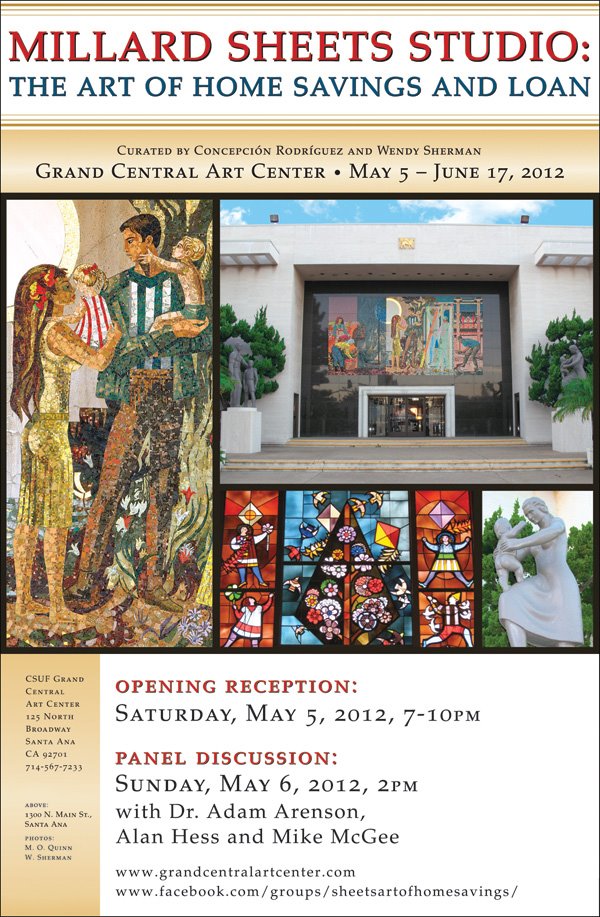

Millard Sheets, Home Savings shield, in Home Savings calendar by George Underwood; courtesy of George Underwood

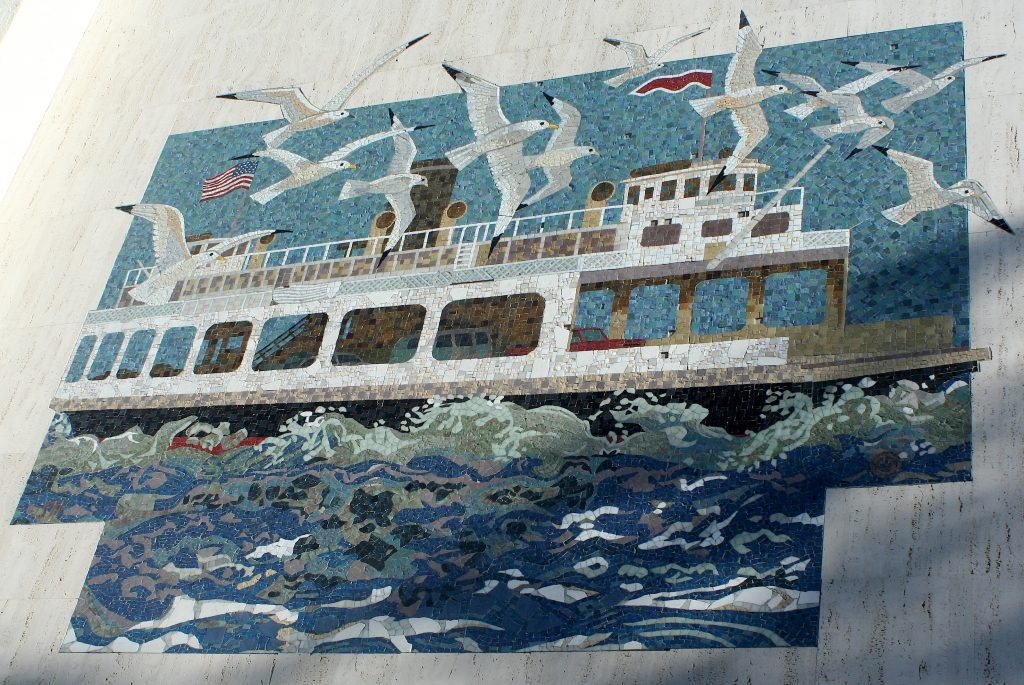

Businesses need brand logos. And so, though the art and architecture of Home Savings were their own sort of branding–prominent corners, eye-catching art, local themes–in 1955 Home Savings needed a brand logo, and Millard Sheets designed this shield. Some of its earliest renditions were in the traditional Home Savings form — mosaic.

Like many successful logos, the Home Savings shield seems simple, through a number of careful design choices. Here words are scaled according to their relative importance–the concept of “HOME” as well as its use as a nickname for the savings and loan makes it an obvious choice for being largest. Next comes “Savings” — you can see below, in other versions, that its prominence was kept, while “loan” began shrinking.

The calendar caption, saying that the shield was “comparatively ‘new'”, reflects the Home Savings gospel that the business went back to 1889–an idea Sheets incorporated into the shield itself. But Howard Ahmanson bought Home Savings in 1947, and all transformations date from there. (See more in Eric Abrahamson’s new book, Building Home.)

Home Savings locations also had the griffin, designed by Albert Stewart via a Sheets connection, which was the symbol of the larger Ahmanson holding company, and today is the symbol of the Ahmanson Foundation. It passed a key test for modern logos — good at all sizes — that recently got the UC system logo in trouble. But nothing about it said banking exactly, despite the reference to the winged lion of St. Mark, symbol of Venice, a longtime global trading hub.

The shield is obviously a symbol of protection, and the background–which at first seems to be an abstract design, like on a tapestry — shows small trees, reinforcing the idea of growth, seed capital, and the power of long-term investment.

But then there is the problem of how to make the shield stand out in two dimensions. In my conversations with George Underwood, who oversaw the inside publishing and advertising efforts that brought us the calendars, advertisements, stationery, and more, he spoke of the agony of figuring out how to make the shield look good.

We can see two of those solutions here: the laying down shield (a photograph of a three-dimensional shield at a dramatic angle) was often used in print and television ads; it positions the viewer as looking up at the shield, as we might from the sidewalk to the side of a building. And it always helps a brand to feel folks are looking up to it!

Sheets and George Underwood, Home Savings shield in 2 dimensions, 1970 calendar, courtesy George Underwood

Then there are the subtle but important design changes in the shield above, in the midst of the rainbow of color. To emphasize the depth and weight of the shield even in a two-dimensional rendering, the top line is bowed out, as in the photograph, and the placement of the letters are also distorted across what would be the bulge at the center of the shield, strengthening the illusion of three dimensions.

Such an important symbol as the Home Savings shield eventually made its way into interior-illumination signage, sometimes on buildings but mostly on standalone signs. The plastic version was crafted by Tony Sheets, and some still exist; at right is a case of how Chase has reused on such existing sign, in Garden Grove. (I haven’t seen examples of how Washington Mutual used the street signs in this way, but they must have done so at least in this location.)

Though the Chase symbol seems incongruous here, the survival of the shield, even as transformed, is something to celebrate. Architect and historian Alan Hess just showed me a Mobil red pegasus that Sheets and his network of sculptors had created for a station at Harbor and Katella in Anaheim though it is long gone. Right now, fellow roadside-architecture preservationists are hard at work trying to save the Unocal 76 balls from being replaced with signs that merely show a picture of them.

When a company disappears or modernizes, preserving items with its logo in public places can be difficult. But, from the Queens Pepsi-Cola sign to the Hollywoodland real-estate origins of that iconic sign, it is possible — and worth doing!