The Last California Home Savings Mosaic: La Cañada-Flintridge

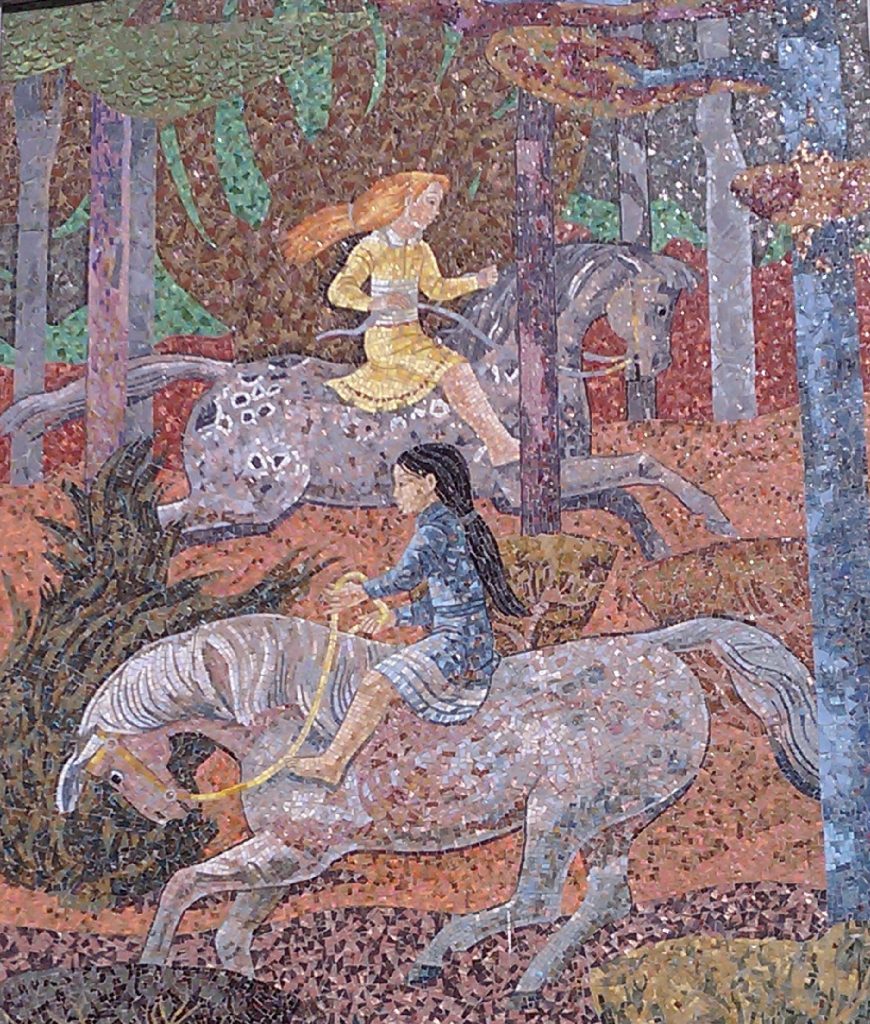

In my last post, I discussed how we should measure the “lasts” of the Home Savings artworks. The Bartels and Preston tile mosaic I displayed is the last exterior work in California; today, the last interior work in California, by the longtime mosaicist of the series, Denis O’Connor. (As I mentioned last time, the very latest from O’Connor are in Illinois and Missouri — Berwyn, Evanston, and then Chesterfield, to be exact.)

I visited this mosaic on a day I had met with Denis’s son Kevin, and had a chance to see some of Denis’s later works and momentos of the decades spent working on projects for Home Savings. Kevin mentioned Denis’s frustration in some of his last projects, battling the difficulties of the mosaic craft, the troubles of older age, and the flagging enthusiasm for these mosaic works.

At the La Cañada branch, the diminution of the Home Savings works is evident: as the electrical outlet in this photograph suggests, the placement of this mosaic is happenstance, in the entry hallway to the bank, which does not have any of the other signals of Home Savings, like travertine facing.

The mosaic is much smaller than the average Home Savings artwork, and it was installed in a metal frame — ready to be carted away as needed, without the cost involved with removing the mosaics from cement and permanent walls, as would be required in most of the Home Savings locations. Rather than placed high overhead, the mosaic is at eye level, allowing a far more intimate examination of the craftsmanship and a tactile appreciation for the tiles, design, and methods.

I have not yet checked the relevant file at the Huntington Library, but I believe what Kevin told me, that the artwork is meant to echo the nearby Descanso Gardens, once again linking the bank to the community. The ducks, roses, and trees over streams in the mosaic match nicely with the images of the gardens available on their website.

Descanso Gardens are a bit of a hidden treasure–a preserve in the San Rafael Hills that held out against the post-WWII transformation of the LA Basin, and a park more muted than the region’s brashest and most well-known attractions. So too is this last Home Savings mosaic in California modest — but, in its intimate size and placement, a treasure worth the trip.

The Last Home Savings – under threat in Woodland Hills

This weekend I was on the Jewish World Watch walk to end genocide in Woodland Hills, strolling with thousands through the mostly deserted streets of the Warner Center early on a Sunday morning. But when we turned onto Victory Blvd., I saw it — one of the last Home Savings banks. I ran off the walk path and snapped some photos.

This branch was in the news in November–apparently, Costco and the mall giant Westfield plan to tear down this former Home Savings to build a big-box store–with its back wall facing Victory Blvd.

This is not the work of Denis O’Connor, Millard Sheets, or Sue Hertel. The artists were Marlo Bartels and Astrid Preston, who had collaborated on two of these late Home Savings banks. (Why Home Savings started contracting artists outside the Sheets Studio is a question I have on my to-research list. Leads welcomed!)

I spoke with Astrid Preston in the fall, who described her efforts to link the mosaic to the community, showing the mix of office towers and residential buildings in a leafy setting, much as the Warner Center/ Topanga Mall environs appear today. The Sheets Studio often started with historical sketches and photographs; this mosaic was more about the contemporary moment, and was researched by driving around the neighborhood.

Doing the math, I figured out that this is the last exterior Home Savings mosaic in California. (According to my records, the last California mosaic is in the lobby of the La Cañada branch, installed 1990, and the last Home Savings banks with mosaics were done in Illinois and Missouri. All of these were done by Denis O’Connor Mosaics.)

So I knew about the bank, but going there provided a few revelations: first, the bank is set deep into a parking lot, typical of a modern mall but unlike almost any other Home Savings location. (Compare to the placement of the Westminster location, adjacent to the mall but still prominent on its own road.)

Second, you can see that there was an effort to maintain the look of the Home Savings bank, as we have discussed, but to try and do so with much cheaper materials and styles. Out went the hand-cut glass smalti; in came the painted, flat ceramic tiles. Out went the large travertine tiles; in came smaller specimens.

And, most tellingly and least effectively, out went the Interpace gold tiles used to mark the roofline, and in came quite inferior metallic gold tiling, vertical and undistinguished.

So the bank has a feel of Home Savings, but not the true romance and beauty of the original banks. I didn’t wander inside, but the interior looked undistinguished as well; I do wonder, as the LA Times article suggested, if the mosaic could be preserved and placed in any future wall along Victory Blvd. — something much more like what the original Home Savings had intended.

*

I will take a break for Passover/Easter Week next Friday; more mosaics to follow after.

Compare and Contrast: Other Corporately Sponsored Public Art

True history needs its points of comparison and the proper context. So in this week away from southern California, I have turned to that aspect of the Home Savings project.

This past weekend I spoke twice in downtown St. Louis, and took the opportunity to visit the local sights again: Busch Stadium, for the Padres-Cardinals opener; the Arch; the Old Courthouse–and the local corporately sponsored public history mosaics.

The cover I originally desired for my first book was a detail from Fredrick Brown’s wonderful mural at the UMB Bank across from the Old Courthouse, focusing on the nineteenth-century figures appropriate to that project. Brown’s work stretches from the era of the Cahokia Mounds to Auguste Chouteau, Thomas Hart Benton, Dred Scott, Abraham Lincoln, Adolphus Busch, and on, to the Cardinals and the Arch; a great sweep of St. Louis history all in one place.

A reception for the Business History Conference brought me back into the Metropolitan Square building, and a helpful suggestion from one of my book talks let me grab the building’s explanatory brochure, and learn how the artist Lincoln Perry has cleverly blended St. Louis sites with the story of Homer’s Odyssey. The then-and-now murals at the front of the building by Terry Schoonhoven (who has done extensive work in Los Angeles, including at the former Home Savings at 7th and Figueroa) showing the courthouse dome before and after oxidation and other details, show the efforts of the building to speak to the history of its local community–much like the Home Savings and Loan art and artwork.

I have found there is a whole company dedicated to cataloging these art collections: the International Directory of Corporate Art Collections and its associated websites, with more than 1,300 corporate art collections listed! So coming up with an exhaustive list here would be impossible, but I am especially curious of other examples.

So this week I have a challenge, dear readers: What examples of corporately sponsored public art comes to mind? (That knocks out collections mostly kept as investments and not constantly on display.) Sculptures are easy, so we will mostly discount them too — I want to find mosaics, stained glass, and murals, and I especially want to know if they depict the local community or history.

Which other corporately sponsored artwork comes to mind when you think about the Home Savings art and architecture?

Home Savings in a Changing Highland Park

Before researching this project, I had never heard of the Highland Park neighborhood of Los Angeles. Tucked away along the Arroyo Seco, on the grounds of the former Rancho San Rafael, Highland Park is one of Los Angeles’s oldest settled areas–but one that has faced generations of turnover, whether in redevelopment that threatened Victorian houses to demographic shifts toward Latinos and then toward “hipsters.”

Visiting Highland Park recently, to see the mosaics installed in the early 1970s, the shifting tides were obvious: the feel on the street, the look of the businesses all around the location reminded me of the working-class Latino businesses of El Paso more than the environs surrounding most of the southern California Home Savings locations. Given the timing of its construction, I assume the contrast is more about changes in the local landscape than an effort by Home Savings to court Latino customers under President Nixon.

The neighborhood is alive with visual culture, however; this is just one of the vibrant painted murals on the alley side of buildings along this main drive in Highland Park. This fall, I am leading a bus tour of Home Savings locations in the San Fernando Valley for the Autry Museum, linked to their Pacific Standard Time exhibit on pre-Chicano Mexican American muralists. Highland Park’s murals are of more recent vintage, but the parking lot behind the bank is one place to take in the contrast.

Two more tidbits from my visit:

When I asked the bank teller about the mosaics on his bank, he pled ignorance; “I’m not from here,” he said, in a way that seemed symptomatic of the difference between Home Savings’ deeply community-based approach and Chase’s more national profile.

And yet another case of Chase’s mishandling of the artwork: this awning does help shade those standing at the ATMs, but did the angles require them to cut into the mosaic–and separate out the Sheets signature–to do so? I can’t say the anti-pigeon-roosting spikes make it seem very hospitable, either.

See you back here April 8th–next week I am in St. Louis, to present at the Business History Conference about Home Savings, and elsewhere about my current book.

Missing Home Savings Art: Mysteries in Santa Monica and Glendale

This week I had the pleasure of meeting Lillian Sizemore, an accomplished mosaic artist who teaches about contemporary and classical mosaic techniques and who knew Denis O’Connor, the mosaic master of the Home Savings bank art, in his last years. (Last week I took a week off for spring break — sorry!)

We discussed the intersections of our research while browsing the Denis O’Connor Collection at the Huntington Library — and Lillian alerted me to a letter she saw, at once heartbreaking and mysterious.

In 2001, Denis O’Connor received a letter:

Dear Denis:

We have removed the two glass mosaic murals from the old Home Savings Bank building located at 331 Santa Monica Boulevard…

…please note that you can have the murals if you are willing to pick them up and pay us for the costs incurred for their removal….If we do not hear back from you within thirty (30) days, we will assume that you do not want the murals.

Leland Means and Denis O’Connor, pelicans and dolphins, Santa Monica, 1988 (demolished; a blurry image, sorry)

As Lillian said, what a heartbreaking thing to receive. Did Denis follow up? What was the cost — a few hundred, a few thousand, or tens of thousands of dollars? The mosaic, from 1988, and showing pelicans and dolphins, was not massive, but the effort to remove it from a demolition site intact would have entailed most of a day.

In any case, there is no record of Denis’s response — and no record of what happened to the mosaics. The company that oversaw the demolition, The Tides Building LLC, seems to have been a part of The Braemar Group; all the phone numbers listed in the letter, or on the Internet, are disconnected. But even if the company went bankrupt, was sold, or otherwise disappeared, the assets involved likely did not–neither the $18.7 million for the building they constructed in the bank’s place, nor mosaics.

Sam Watters, in his March 2010 Los Angeles Times “Lost LA” column reflecting on the themes of the Home Savings artwork discussed every week on this blog, mentioned the site as “reduced to rubble,” but we can assume that was hyperbole rather than a confirmed kill, until we hear otherwise.

Have you seen them? Are they in your backyard? Did you write this letter, or were you involved in the Home Savings’s building’s demolition? Historians, and some interested museums and collectors, would love to know!

So that’s the Santa Monica mystery for today. As for the Glendale mystery above: the records I have searched suggest no artwork was designed for that site, so perhaps the construction crews simply cut a hole for artwork that was never to be there. for the Home Savings shield that was once there.

But the records are also incomplete–do you remember artwork in that spot, facing the parking lot off Brand in Glendale? If so, let me know!

A Tree Grows in Claremont

February turned out to be a busy time–so much to do, so few days to do it?–and the start of March offers no let-up. Most of the time I am happy with so busy–research, writing, conferences, commuting, teaching, grading, and that is just for work–and it beats having nothing to do, though that seems an impossibility nowadays.

But it has meant that I have not been out on the streets, tracking down Home Savings and Sheets Studio archives and statuses that much recently. At least spring break is coming soon.

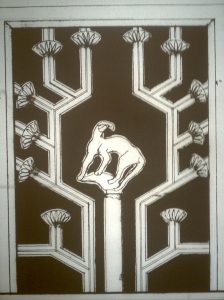

So, looking through my own Home Savings photo archives, I was struck today by the calm of this simple mixed-media tree with birds, completed by the Sheets Studio and affixed to the end of an office building in Claremont. (I think it it is on 4th, between Harvard and Yale avenues.) It seems a perfect image for spring.

Trees and birds seem to have been almost as important totems for Millard Sheets as horses; from his home in Gualala to numerous compositions in many media, the tree filled with the sights and presumably sounds of birds reflected a sense of contentment and joy that the Sheets Studio work exudes.

I assume this is an early piece, as the mosaic tiles are used merely as background, and the birds and tree is represented in three dimensional ceramics, some with colorful accents. What comes to mind are other earlier works — the sculptural birds and trees, as well as other animals, by Betty Davenport Ford, and the marvelous bull at the LA County Fair’s Millard Sheets Center for the Arts building, completed in 1952 by Albert Stewart and John Edward Svenson. Like the tapestries, they represent the efforts to use color and modernist lines to rethink traditional art forms, as Picasso, Miró, and others were doing in these same years.

This is at least as labor-intensive as the glass-tile mosaics, harder to install, and likely far more brittle, so harder to maintain. Nevertheless, this example has held up wonderfully–and likely adds a quick, upbeat note to all those who notice it, as they walk in the leafy, sunlit streets of Claremont.

Lion of the Valley: Betty Davenport Ford at the Encino Home Savings

The last Home Savings and Loan completely conceived by the Millard Sheets & Associates, in concert with Frank Homolka & Associates as the architects of record, was the expansion and renovation of the Encino branch at 17107 Ventura Blvd.

This branch has practically a whole wall of stained glass, mosaics inside and out (though the interior vault mosaic is now hidden), a large interior mural, and statues in niches — as well as a pair of ceramic mountain lions, enclosed in decorative grilles. Given the volume and variety of Sheets Studio artwork in this branch, it may be the most comprehensive look at the Sheets Studio’s production, given the variety of subject matter as well as media.

The year 1976 was one of the busiest for the Sheets Studio with Home Savings; we have seen artwork conceived or completed from that year in La Mesa, San Francisco, and Tujunga, with other projects in Alhambra, Redlands, Torrance, Buena Park, La Mirada, Lakewood, Simi Valley, Menlo Park, and Barstow still to come. It was also the era of the press-release or brochure at the opening, to give us a sense of what we see:

Designed for Home Savings by noted artist Millard Sheets, the two-story building occupies 12,030 square feet…

Two forty-foot[-]tall cast stone grill[e]s, designed by Tony Sheets, embellish the exterior while shading the large picture windows behind them.

Sculptress Betty Davenport Ford created two 1000[-]pound mountain lions which are ensconced on pedestals in the grill-work. Each larger-than-life animal was directly modelled from clay, slip-glazed and fired. They represent some of the largest works of this kind ever executed.

Like Sam Maloof, Martha Menke Underwood, and some of the other of the very best Pomona Valley artists, Betty Davenport Ford spent a period of her career contributing to the Sheets Studio artwork before dedicating herself completely to a solo career, creating sculptures of the natural world, distinctively stylized. At 88, she is still involved with the world of art ceramics, and her work is present in museum collections around the country.

These lions provide an interesting twist on the idea of connecting to the community. The winged lion of St. Mark, as seen in Venice, Italy, was the symbol of Home Savings, but this large cat is a local–to this day, the San Fernando Valley is sometimes visited by the region’s mountain lions, this big in the minds of the suburbanites who encounter them (though not this large in reality.)

I have to think more about if the art of the Encino branch has a unified narrative–from mountain lions to working men and women, to farm animals and birds to a cowboy on horseback–but the lion could mark the earliest, primeval sense of the valley, especially given the local La Brea tar pits, and the remains of the megafauna–saber-toothed cats, wooly mammoths, dire wolves, etc.–that were found there in number. It takes the winged lion and says hey — take a look at this local lion instead!

Though partially hidden by trees now, these lions in Encino announce proudly how Home Savings would guard that money.

Remember the Alamo—or not: Sheets and Associates in San Antonio

Millard Sheets, "The Death of Travis," detail of lithograph, San Antonio, 1966 via http://www.parkitecture.org/wordpress/?p=332

We often think of Millard Sheets as a California artist, and the Home Savings banks as a California phenomenon. Sheets was born in California, and did the vast majority of the bank projects in California—but there are other public-art projects, in Arkansas, Georgia, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, Washington, D.C., and Hawaii. (A full list, with dates, addresses, and current status is coming – I will finish it one of these months!) There are Home Savings banks with Sheets and Associates art in Florida, Illinois, Missouri, Ohio, and Texas, where Sheets, in fact, did one of his first banks, the Dallas Mercantile Bank, in 1958. This past week I had the pleasure of helping Scott Stoddard with stories for the San Antonio Express-News about a massive painting of the battle of the Alamo in the former Travis Savings and Loan in San Antonio. As he describes here, here (where I am quoted a few times), here, and here, the bank building was bought by the San Antonio Independent School District in 1994, and is currently in closing for sale to a new developer. The building has been empty, and Stoddard initially could not even get in to see the painting—but the latest story is accompanied by breathtaking pictures of the mural, 20 feet tall and 32 feet across. According to the latest report, the new owners plan to remove the painting and donate it to a museum. The mural is rich with action—from the perspective, we stand with the Texans with guns pointed over the ramparts, firing cannons as uniformed Mexican soldiers climb up the walls with ladders. The painting’s perspective runs deep, showing mesas and thunderheads, and what appear to be cattle trains in the distance. At the center—highlighted by a white shirt and a simple, unmistakable gesture of being hit—is Col. William B. Travis, one of the leaders of the Texan Revolution to be killed in the fighting. Even teaching in El Paso, far from San Antonio, the basic mythology of the Alamo and its importance to Anglo Texans has become second nature to me. Stoddard wonders whether this may be the largest painting of the Alamo anywhere in the world, and has worked to get estimates for such a large, intricate work, with suggestions running into the hundreds of thousands. I am glad the painting is getting attention and will be preserved, and I plan to learn more about it in the archives soon.

But something I did see this week in the archives of the Texas projects provided another perspective. The Texas Home Savings banks came later, in the late 1980s, and so their artwork was commissioned from Denis O’Connor and Sue Hertel, Sheets’ former assistants on these projects who had begun working for themselves. One such mural was done for the Castle Hills branch, at 2201 NW Military Hwy in the San Antonio region. The final design, of horses, cowboys, and their animals, reflected direction from Richard Massey, the local bank manager, “to use scenes of early Texas Pioneer cultures (German, English, Irish) over a background of wild flowers.” UPDATE: Scott Stoddard emailed a sharp photo of the Castle Hills image, to add to his great images of the Travis S&L mural.

In processing another recommendation that “the Spanish influence was good, but overdone,” Denis made a quick note in his planning: “No Alamo – Mexicans, etc.,” hinting at how the Texan Revolution—and especially the all-out war between the U.S. and Mexico that followed in 1846—was a bitter memory for many long-established Hispanic families or newer Mexican American residents, and something to avoid when courting new bank customers.

When it comes to remembering the Alamo, then, Millard Sheets and Associates were ready to be on both sides. We can be too—in seeing that both are preserved.

The Breadth of Communication in the Loyola Tapestry

Millard Sheets (design), Pinton Freres of Aubusson, France (fabrication), Loyola Tapestry, 1964-1966

In late December I had a chance to go see the Loyola Tapestry — one of the most detailed and clearly the most labor-intensive of the Sheets Studio projects, surpassing the “Touchdown Jesus.” It is obviously not bank art, but it is art intended for public display, reflecting on world history, and an amazing example of Sheets’s work in another medium.

Conceived as part of a gift from Edward Foley for a communications art center designed by Edward Durrell Stone, only the cartoon stood ready at the building’s dedication, in January 1964. According to documents I found in the LMU archives, it took seven weavers (working an inch a day) two years and three months to create the tapestry, which is reputed to be the largest modern tapestry in the Americas and the third-largest in the world. Eighteen feet by thirty-four feet, it was hung in March 1966.

According to the press release, the design emerged from “long and serious analyses of the them concept” by Rev. Charles Casassa, S. J., the university’s president at the time, and Mr. Foley, working with drawings that Sheets evidently provided.

What is even more remarkable is the extensive description Sheets himself provided for a pamphlet at its dedication. A few words of description exist for many of the bank openings, but nothing like this:

The Loyola Tapestry, especially designed for the foyer of the Edward T. Foley Communications Arts Center on the Loyola University of Los Angeles campus, symbolizes the meaning and means of communication created by man.

The total theme has been divided into three basic areas: communications from man to man, from man to nature, and between God and man.

The central figure of Christ with the Wings of God symbolizes man’s search to understand the Infinite and his own spiritual faith.

On the extreme left side of the Tapestry is the theme of communication between man and man. The symbols of scholarly and creative expression are noted in the small vignettes that surround the two figures indicating brotherly love. The smaller symbols of the Renaissance scholars, the Magna Carta signing, the United Nations, missionaries, the various arts are all facets of man’s desire for cultural, social, and political understanding. The small band of symbols at the bottom of the Loyola Tapestry on both sides are expressive of the techniques man has developed as means and methods of communicating. Various alphabets, printing, telephone, motion pictures, and communication techniques are included.

On the right side of the Tapestry, communication between man and nature is pictured by the central figure of the young man’s love of plant and animal life. The smaller symbols represent man and his use of fire for warmth and cooking, the domestication of animals, conquering of air, water for food, and related ideas.

The total theme is designed to indicate many of the great accomplishments of man in insight and inventiveness to express the variety of urges and feelings he needs to express to others.

I would also hope that in the spirit of the Loyola Tapestry the beholder will sense the possibilities of the infinite future of new and greater means of communication that lie ahead if discipline and imagination are matched with a deeper desire to face the great problems of our times. Man desperately needs to improve all present techniques for communication. He must determine greater objectives for each separate language and skill if mankind is to enjoy a future with assurance and depth.

On its edges are quotes from the Gospel of John, the 12th-century Chinese poet and painter Fu T’ung-Po, and the 20th-century Jewish philosopher Martin Buber; add that to the Pony Express, the United Nations, the large figure of Jesus, and you get quite a capacious image of communication. It also makes an interesting contrast with Cold War-era brochure about the need for such a communications center: “In olden days the enemy poisoned wells,” it declared. “Today the enemy poisons men’s minds,” and hence it was time to fight back with communications arts–marketed quite differently today, amidst the cell phones, Facebook revolutions, and satellite TV.

How exactly this all came together — that Foley decided he wanted artwork in the foyer, and to pay for a tapestry rather than a mosaic or painted mural; that such a wide-ranging set of quotes and images were best for the new communications building at a Jesuit college; and that Sheets, as a Protestant, became the artist of choice for Catholic institutions from Loyola to Notre Dame to the “Triumph of the Lamb” in the Basilica of the National Shrine in Washington, D.C. — remains unknown to me. I do know that Martha Menke Underwood, who had worked in Sheets’s studio, was dedicated to the art of tapestries in these years, and that the Sheets Studio had produced some tapestry designs for banks as well.

Thanks to the LMU Archives for their help in finding and copying items from their collections.

Millard Sheets’s Gateway to the Pacific and the Home Savings Style

Following up last week’s post and staying at San Francisco’s West Portal, if we walk outside, we encounter the most international of the Home Savings artworks, the Sheets & Associates “Gateway to the Pacific” mosaic.

The concept of a Pacific Rim, interconnected by commerce, entertainment, migration, and cultures, is an old one — statues in Easter Island suggest that these connections may predate Christopher Columbus’s voyages. But the 1970s saw a return to thinking about the Pacific Rim, with President Nixon’s visit to China, the rise of the Japanese economy, and the start of the “Asian tigers” economic phenomenon, and the flood of goods made in Japan, Taiwan, or Hong Kong.

The representative figures from each Pacific Rim nation come in pairs, a man and a woman, and each is engaged in what might be seen as a representative task, a labor linked to agriculture. From what I can tell, the Mexican couple carries flowers (calla lilies), the South Pacific pair a fishnet and fruit; the Californians wheat (I think; very hard to tell); the Australians care for sheep; and the Japanese carry also carry grain bushels.

The figures do not interact, and do not appear in geographic order; four of five men wear sunhats. Only the Japanese woman looks out at us; all the rest are engaged with their labor, or the labor of their partner.

This is a very unusual work, not only for the international theme. Besides the large sun overhead, which (given its inclusion in the Beverly Hills, Encino, and other mosaics, is a kind of Home Savings theme), there is no way to look at this and say, immediately, this was a Home Savings artwork.

What it looks more like was the artwork that Millard Sheets created after his trips around the world, and in commissions for United Air Lines and other international-themed places. Though exhibits like the LA County Fair exhibit organized by Tony Sheets highlighted this international side of Sheets’s work, it seems a world away, literally and figuratively, from the standard Home Savings topics and designs.

Given the radically different artwork that Sheets, Hertel, and Denis O’Connor created independently, outside of the context of the Home Savings work, makes me wonder where the “Home Savings style” originated. Sheets did the original designs, and so the answer lies with him, in one sense, but — the early works like Beverly Hills also feel atypical, in their way, and Sheets, in any case, had to have some idea of what Howard Ahmanson wanted for Home Savings.

Sheets chose California community themes, but were those works only possible in one style? Clearly not. Mosaic makes certain demands; so stained glass, and so Sheets and Hertel, painters by preference, made concessions to form. But the differences so evident here — the colorplay in the tiles, the abstracting lines, the sun are the same, but the figures seem cut out of a totally different scene.

Which Home Savings artworks seem not like the others to you? (I have another in mind, which we can see next week.)