Image of the Week: Dating Mosaics and Thinking of Home in San Diego

Last Friday I had a chance to sit down with Alba Cisneros — a mosaic artist who worked with Millard Sheets and Denis O’Connor for 17 years — and Katy Hertel, Susan Hertel’s oldest child (a stepdaughter), herself an artist and, like many of the artists’ children, a sometime worker in the mosaic studio.

Sitting at a mosaic-composition table, surrounded by cans and cans of tile, trying my hand at cutting and shaping a tile (not very well), we talked about many of the stages in the history of the mosaics — and I gained a good amount of insight into composition and dating of the mosaics.

In December I plan to return to the task of creating a comprehensive list of the Home Savings locations with Sheets Studio art and architecture — and which are threatened (for now, this list which I am no longer updating will have to do).

But one of the key questions is dating the works — which was from the Sheets-Ahmanson period, ending with Ahmanson’s death in 1968? Which is before Sheets turned over all of the Home Savings work to Sue Hertel and Denis O’Connor, in about 1980? Some archival files exist, but the expertise of Alba Cisneros, who started working for the studio in 1975, can, with others, help to date the artwork even when file, newspapers, or other sources come up short.

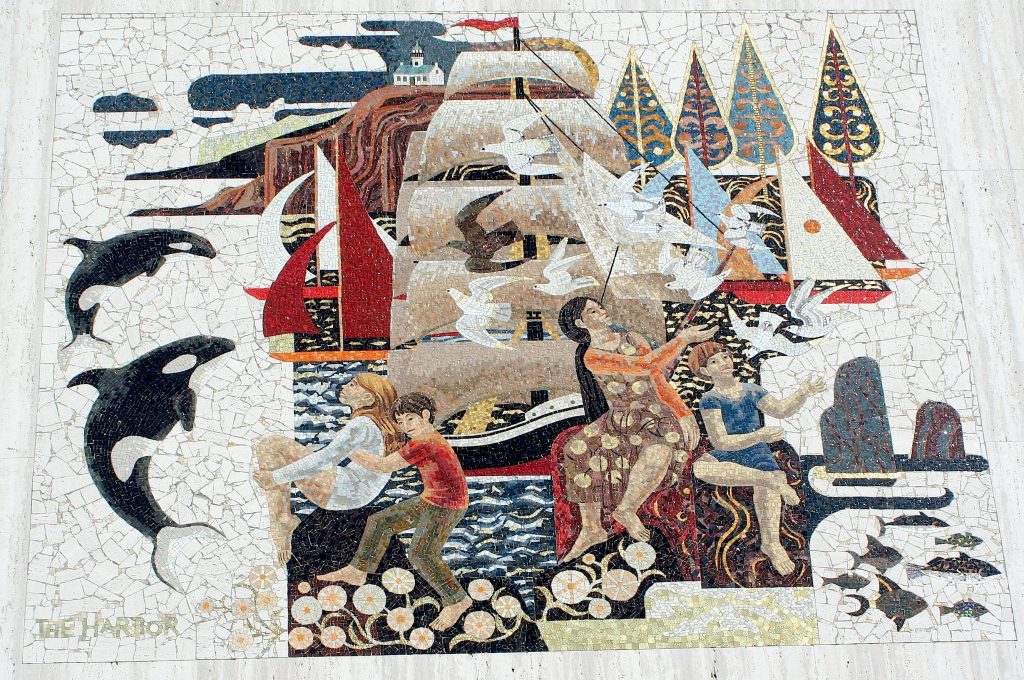

Alba remembers working on this mosaic, and has pictures of it in her personal files — and Katy looked at many of these images (I think this one among them) and said, “That’s my brother!” I learned that Sue Hertel — working every day in the Sheets Studio, then returning home to her children and a house full of horses, goats, and chickens — often drew inspiration for her family scenes directly from her own home, with family portraits included in each embrace.

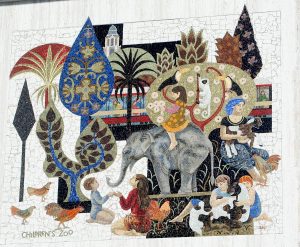

Katy and I specifically addressed the Westminster Mall family, which I discussed a few weeks back; this companion to “The Harbor,” showing, ostensibly, the San Diego Zoo’s children’s pavilion, seems to also reflect what I have heard about the Hertel homestead. (Both of the images, facing the parking lot, can be seen together here; I will come back to the masculine portraits on the front of the bank another day.)

I grew up in San Diego, going to the San Diego Zoo, caressing the chicks, seeing the orcas at Sea World (the world’s first, which opened with Shamu in 1964), playing in the tidal pools, riding the Balboa Park miniature railroad, standing near the California Tower, cavorting about the clipper ship The Star of India, and going out to the Point Loma lighthouse; in recent years, I have been privileged to do many of the same things with my toddler.

So the sense of place, of what San Diego is like for a young family, is very strong for me in these images. But, as we have seen, Sue Hertel blended her own family history into the images and ideas of the place she was depicting — and the San Diego Zoo was not allowing any elephant rides in my memory. So the images are, as we have seen, a mix of the specific and the generic, the historic and actual and the nostalgic and fanciful.

One more note on the mosaic workmanship and the dating of the images: Alba explained that, originally, each element of the mosaic would be placed within the travertine facing of the banks — and even small elements like trees or the silhouette of a sail would be carefully cut out. But after a while some cost-cutting did occur, by making more rectangular, easy-to-install shapes, and/or, as you can see in this image, using broken travertine to fill in the background and allow for the smooth visual connection to the rest of the building, without the difficult cutting.

Alba also explained that, once the mosaics were installed, members of the Studio would get up on ladders and stain elements of the image, to cover the grout, for example, with the dominant color. I think we can see a further element of “cheating” here, as the tops of the trees in the Children’s Zoo image seem to be merely painted onto the travertine above the mosaic.

I’m glad that, this Thanksgiving, I will have a chance to revisit these images, alongside my family.

The Case for Preservation in Pomona (and for Communication from Chase Bank)

In the past month, scaffolding has gone up around the Home Savings tower in Pomona, at the corner of Second and Garey. Local preservationists were disturbed at this development; less than fifty years old, and part of the modernist moment in art and architecture just now being preserved in Pomona, Los Angeles, and across the nation, they were worried about what exactly was going on. (See news and comment.)

Questions have been raised, from what is Chase Bank’s intentions, to whether such a tower is worth preserving. So this week I will take those ides on–in reverse order.

Why preserve this tower? Well, the first thing to know is that it was conceived as part of the same project as the Pomona downtown mall, a novel project for its time in using the allure of downtown, plus a few fountains, sculptures, and mosaics, to draw in locals on their lunch break and visitors to town. Built as a pedestrian mall, the Pomona downtown mall was one of the earliest examples of the attempt to replicate the shopping Main Streets that anchored thousands of U.S. towns in the era before the highways overran that landscape.

If that doesn’t speak to you, consider the building’s interior:

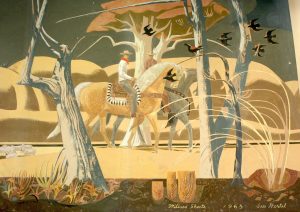

A wall-to-wall painting by Millard Sheets and Sue Hertel, one of the first (if not the first) which she signed, marking her transition from Scripps College art student to full-fledged member of Sheets’ artistic studio. The jagged-shaped birds, rolling abstract hills, and horse motifs seem very much like Sheets, but there is a warmth, both in this painting and the outside mosaic.

This suggests the scenes of family embraces, curvilinear, organic shapes, and subtle but striking color choices that would mark much of Hertel’s best work as a painter and Studio member for decades to come.

The mosaic is near-impossible to remove; as long as the building is standing, it will be there, one assumes. And the painting, though massive, must have found some way in; it is probably on panels, and so, if Chase needed to remove it, it could.

But that leaves the overall design of the building itself, something no one photograph can really capture. Once you look closely at the window latticework, you can see the H-S of Home Savings, one of the marks of the early, “signature” banks personally overseen by Millard Sheets and Howard Ahmanson. (Some of the later iconic elements — a golden lion of Venice symbol by the door, and the marble facing — are also present.) As some have noted, Sheets’ Studio provided artwork for about 160 banks, but the partnership of Ahmanson and Sheets only worked comprehensively on about 45 banks, before Ahmanson died in 1968.

I have not been inside the upper floors, so I have no idea what it is like to work there today; it is a modernist icon, but like many modernist architectural icons, the spaces could be poorly adjusted to the needs of modern office life, or they could be perfect.

My first hunch is that the scaffolding is nothing to worry about; Chase Bank has had trouble with the painting over of a fresco mural in San Francisco, and the removal of the paneled mural in Pasadena, but it seems Tony Sheets (Millard’s son) has been able to work with the company — when the public and the media are alert enough to get him involved. And there is the California Art Preservation Act, which (with its federal counterpart) should at least help slow any changes to a considered pace.

But what is really needed is a true commitment from Chase Bank, to learn about the work of the Millard Sheets Studio, and to create a general plan for how the bank will steward this art and artwork.

The Sheets Studio work was the pride of Home Savings, financed, researched, carefully crafted, lovingly maintained, even through remodels. Washington Mutual, by all accounts, was quite aware of this heritage when they bought the banks, and they seem to have considered how best to maintain that Home Savings ambience in these branches.

But Chase, on the other hand, seems to have brought in their own models, angering customers and losing the local touch in the meantime. This very Pomona branch has a key example:

The Plexiglass that Chase has installed in front of the tellers, distorting and blocking the view of the Sheets-Hertel painting. The same seems to be true in many of their bank locations — the need to place white-and-blue themes, the perfect logos, and these Plexiglass shields (which of course make me feel less safe when I am banking, because the bank is telling me there is something to fear). Home Savings intended their banks as a place individuals could spend time, discussing their investment options, resting their feet, enjoying the “living room” feel; Chase seems to want you to come and go quickly, and if you want a personal touch, perhaps the ATM would be better.

Somewhere, Chase has the institutional records of Home Savings; through projects like mine, and interviews with those involved in the creation and preservation of this art and artwork, JP Morgan Chase Bank could be part of the process of honoring and understanding the gift that Howard Ahmanson, Home Savings, and the Millard Sheets Studio gave to California. In a few cases, Chase has made the effort and paid the expenses for restorations — but these are counterbalanced by the ignorant mistakes made to destroy the artwork in other branches, the lack of communication in cases like Pomona.

So the scaffolding in Pomona can be a wakeup call — both to alert preservationists and bank customers, to ask questions and be sure to announce any such changes. But more importantly, it should be another chance for Chase Bank to truly engage with the history of the art and architecture of the Sheets Studio banks — and to have a chance to be part of the community , as Home Savings and Washington Mutual were, aware of the local history and tradition — and not just another anonymous, disliked national chain.

Image of the Week: Location, Location, Location in Westminster

My computer has returned, and with them my images — but there are still some loose ends that prevent me from posting my own photograph today.

However, I was pleased to be contacted by M. Danko, who has begun producing lovely photographs of the Home Savings bank art at http://socal-bank-art.blogspot.com/.

As I mentioned earlier, I was in Westminster for a planning meeting linked to my other Southern California avocation, the Past Tense seminar at the Huntington Library. Getting off the freeway, I saw this bank, and then had to maneuver a collection of one-way streets, frontage-ways, alleys, and parking lots to get back to where I could see the bank.

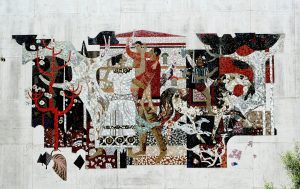

This is a “late” image, near the date Millard Sheets turned over these commissions completely to Susan Hertel and Denis O’Connor. It shows Sue’s styling — flowing lines, organic motifs, family groupings, beautiful abstract trees, contrasting colors. According to the city’s history page, Westminster was known for its temperance colony, and then for “the world’s largest goldfish farm” (probably a large farm, not a large fish) — I can’t say I see any of that represented here. It seems more of a generic design — happy, embracing family, no real connection to the local history, something that does characterize a good number of the artworks.*

From another of the SoCal-Bank-Art images, here, you can see that the bank is set back on the lot, its parking behind; what this Google Maps aerial shot reveals is that behind that is the 405 freeway and the Westminster Mall.

This is a hard bank to get to, I realized, and I wondered if it had always been so. The Westminister Mall was built in the 1970s, so it seems the bank always related to its neighboring properties as it does today; perhaps once the streets were not one-way, when the freeway was less crowded, but this Home Savings location was clearly aimed at mall patrons, much as the Pomona location anchored one end of the downtown pedestrian mall.

This artwork–especially, by the 1970s, when it would have been instantly recognizable to southern Californians–clearly serves in part as a billboard here; the dimensions are about the same, and the combination of the setback and the roadways suggest it was intended to be seen from the car, not admired by passersby.

Indeed, the mall seems essential to the identity of Westminster, California — so much so that Westminster city officials have a satellite office, City Hall at the Mall, to cater to their constituents. So while the bank does not have the approachability of, say, the Sunset and Vine location, it still serves an iconic function, saluting all those that enter the mall, the heart of this community.

*I am trying to provide a new and more comprehensive list/map/timeline of the Home Savings bank art, characterizing some as “historical” along with other themes. I have had a chance to interview some of the architects involved with siting and designing the Sheets Studio work; I am also in touch with those who installed, fabricated, and restored the works, and I am trying to keep abreast of the preservation challenges. So, keep posted, and keep in touch with any leads!

Technical Disappearance

Hello–

My laptop has what IT says is a hardware issue. So they took it away, for at least a week — with all my notes inside. (Don’t worry, I have a backup.)

So the Image of the Week will have to take an unscheduled vacation — but we should be back in business in the weeks ahead…

Image of the Week: California History Encapsulated in Studio City

Now that we have taken a tour of all the various media used by the Millard Sheets Studio, I will focus in on the images and juxtapositions that first drew this historian of nineteenth-century North America to this project about post-World War II Southern California.

Before I learned that there were so many, and so varied, artworks in the Home Savings banks, my mind fixated on the history images, in grand, prominent locations, like the parade of figures at Garnet in San Diego, the collection at Sunset and Vine, or this mosaic, commanding an entrance to the San Fernando Valley in Studio City.

In four figures, this Sheets Studio mosaic tells one story of California history, expanding on the history of “From Oranges to Oscars” discussed last week. The Franciscan friars came to Christianize California’s Indians; California’s frontier was a place of vaqueros, ranching and cowboying according to Spanish and Mexican traditions before the coming of American control; the gold rush changed everything; and, in this rendition — presto! California was ready for the magical transformations of Hollywood moviemaking.

Clearly, a lot is missing from such a history. But I would rather focus on what draws these four scenes together, and how they might have been chosen to tell their story together, on the bank facade, in giant figures.

First, these are clearly picturesque moments in California history, moments long remembered for their adventure or intrigue or possibilities. As I have noted, there is an attempt to tell happy, uncomplicated stories — no Okies arriving out of the Dust Bowl, no Zoot Suit riots, not even the proud shipbuilding of Californians during World War II. We academics now have a greater sense of the displacement caused by the Missions and the gold rush, but they remain storied moments in the public’s perception of California history. And perhaps their rootedness, their long histories, was intended to rub off on the new movie business, and the new bank in the still-newly-suburbanizing San Fernando Valley.

Are the images about history, or about movies? Given the gaps and the connection to nostalgia, it can be hard to distinguish the two. The camera does point left, taking in the dramatically dressed woman but also, perhaps, the character drama of a Franciscan friar, a vaquero, or a prospector, each a common figure in the radio dramas, films, and television shows of the twentieth century.

One formal question to ponder, too: Why the tricolor background? Merely to highlight the colors, and give a chance to add depth to the figures? Or something about the amounts of marble needed for such a large space? One more thing to research, I suppose.

Image of the Week: Howard Ahmanson and the Home Savings Art

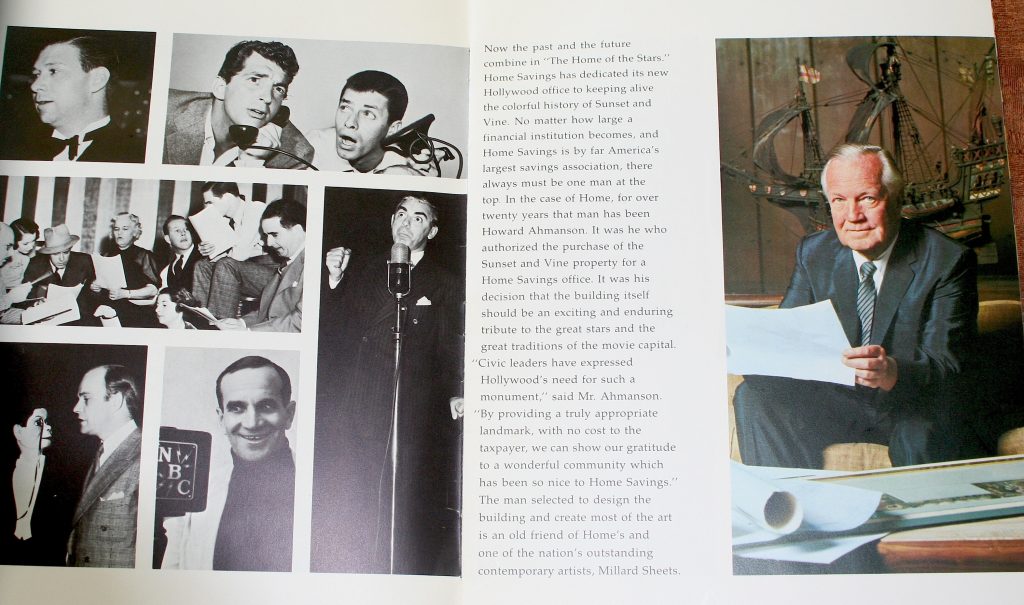

An excerpt of “From Oranges to Oscars,” showing the stars to be honored and Home Savings president, Howard Ahmanson, 1968

The Millard Sheets Studio could create the fantastic art of these banks because they had the financial backing of the Home Savings banks, to create these ornate and expensive pieces of artwork. Hence, as much as Sheets, Denis O’Connor, and Susan Hertel can be credited for these gifts to California, the financial muscle and some of the visionary designs should be attributed to Howard Ahmanson.

Howard Ahmanson Sr. had been born in Omaha, Nebraska, and, while attending the University of Southern California, founded H.F. Ahmanson & Co. In 1947, the holding company purchased Home Savings and Loan; in the decades that followed, the bank profited from lending to the residents of new tract homes and other houses throughout southern California, in its boom years. In the mid-1950s, Ahmanson built a Home Savings along Wilshire in Beverly Hills, his first second (see comments) experiment in a partnership with Sheets’s studio; given the enthusiastic response from depositors, Ahmanson continued the arrangement, as good for business and for the community. Tragically, Ahmanson died of a heart attack in 1968, at the age of 62 61, while traveling abroad with his family. (This quick bio is derived from the account in Vickey Kalambakal’s recent article; a true Ahmanson biography is underway.)

This image of Ahmanson and the Hollywood stars he wished to honor at Sunset and Vine comes from a brochure that Home Savings produced to celebrate the bank’s opening, titled “From Oranges to Oscars.” Once again, the whistle-stop tour of California history is on display; more about that another time.

But the text here is itself a remarkable peek into the intentions of the artwork:

Now the past and the future combine in “The Home of the Stars.” Home Savings has dedicated its new Hollywood office to keeping alive the colorful history of Sunset and Vine…

“Civic leaders have expressed Hollywood’s need for such a monument,” said Mr. Ahmanson [who died soon after the bank’s opening, on a trip to Europe]. “By providing such a landmark, with no cost to the taxpayer, we can show our gratitude to a wonderful community which has been so nice to Home Savings.”

Could the artwork be intended merely as a thank you? Or would the promise of increased attention and free publicity for a grand opening lead to more deposits and hence profits? Did actors and movie professionals generally like banking at a place decorated by the images of their craft? Did anyone dislike these mosaics — not for artistic choices, but for something about the mere idea of public art upon a bank?

Not to seek out cynicism and discord — even as an academic, we can believe in happy stories — but I do hope to learn more about the economics, the cultural choices, and more that went into creating these images. I don’t think there was a tax break awaiting the creation of beautiful, rather than merely functional, bank spaces, so I do hope to learn more about the motivations, for Sheets, his studio, and their first Home Savings patron, Howard Ahmanson Sr.

Image of the Week: Panorama of Pomona Valley, in the new home of AMOCA

Millard Sheets mural "Panorama of Pomona Valley," 77 feet long and 7 feet tall, in a former Pomona First Federal becoming the new home of AMOCA. Photograph courtesy of Christy Johnson

I am proud to be part of a big announcement in Pomona arts! Here are excerpts from the letter from Christy Johnson, director of the American Museum of Ceramic Art:

I have great news! Mr. David Armstrong, AMOCA’s Founder, and his wife Julie are buying a nearby building in Pomona that David plans to make into a new home for our museum. The building is the former home of Pomona First Federal Bank at 399 N. Garey Avenue. The building itself is historic, exuding a mid-century modern décor, and the pièce de résistance is a Millard Sheets mural in the main room, “Panorama of Pomona Valley,” 77 ft. long & 7 ft. high, portraying a 100-year span just prior to the founding of the city. When the structure has been renovated to meet AMOCA’s needs, the Armstrongs will make the space available to the museum just as they have at our current location, for the last six years.

As a way of introducing this project, AMOCA is holding an open house at the new building on Sunday, October 17, from 2:00 to 4:00 pm. This is your opportunity to get a sneak peak at the spacious building, before the renovation begins. Wine and refreshments will be served.

AMOCA educates by presenting, collecting, and preserving significant ceramic achievements, past and present. To meet its objective, AMOCA has amassed a 1000-object permanent collection. The museum’s educational program stresses the unparalleled, cross-discipline value of ceramics: it is an art; a science; and a key to interpreting history.

And now, AMOCA will be able to expand their display space, develop ceramics studios, and more, in the expansive, prominent new space on Garey Avenue.

As Christy mentions, the museum’s move will benefit fans of Millard Sheets Studio art because this massive mural will be accessible to the public once again. Pomona First Federal was one of Sheets’s first bank clients; if my sense of the situation is correct, his artwork for the local chain predated his work with Home Savings. But Pomona First Federal was closed by the FDIC in 2008, as a “failed” savings and loan; hence when I drove by the Garey location in August with Brian Worley, we could only see the outside of the locked and empty buidling.

The location is a prominent one in Pomona, between the downtown mall and the freeway (and train) access points; it will helpfully expand the revitalization of Pomona’s downtown area around its vibrant arts history — and present, and future.

I have not been able to see this canvas mural in person, so I will comment on the image you see above, and some crosscurrents with other Sheets artwork. As Christy states, the mural depicts the hundred years of change before the opening of the bank (my records suggest 1957 for this location). The two centuries from the arrival of Junipero Serra and the mission system, through Mexican independence, the U.S. acquisition of California, the gold rush, and further town-building and modernizing is a favorite Sheets Studio time period.

As I will discuss in coming weeks, there are figures seen as representative and beloved that appear again and again — vaqueros, American Indians, Victorian ladies — but this mural (at least the section above) seems very engaged with the native peoples of the region, their customs and rituals, and how the establishment of the mission (at the center-right of the image above) brings change, for better or worse, to the native patterns of the region.

Sheets grew up in Pomona and loved horses — and his love for the region, and its specifics within the general history of California, come through here. Sheets also collected “pre-Columbian” Native American art, something I am learning more about. But clearly the influence of such ceramics and other artwork is on display in the colors and choices Sheets makes in depicting indigenous people — always with dignity and distinction, in the artwork I have seen, equal partners in the encounter of civilizations that marked the “discovery” of the Americas by Europeans.

I do look forward to celebrating with AMOCA in the coming months and years, and I am glad that David Armstrong will be securing its future!

Image of the Week: Murals and Paintings in San Francisco

The last medium to discuss is painting. Millard Sheets and Susan Hertel both had careers as painters; indeed, they met in the painting studios of the Claremont Colleges, where Susan was a student and Millard was teaching.

Because the paintings are mostly inside the banks, images of them can be rare to find; trust me, nothing attracts the eye of a bank manager like a camera inside a bank! (I must say, though, that both the Washington Mutual and the Chase bank managers I have met have been very interested in this project, and sympathetic of its need for documentation. Those images are for reference, rather than publication, right now, though.)

I do happen to have some images from the Lombard branch in San Francisco — an explosion of art, with stained glass, mosaics (though mostly hidden by trees now, the slides in the Denis O’Connor Collection at the Huntington Library reveal their true beauty and sophistication), and a long, frieze-like painting inside. The Sheets Studio paintings are not truly murals; even the largest, as far as I can tell, is on canvas, and hence can be popped off, rolled up, and removed as needed. (This is what Tony Sheets did to the massive painting in the San Jose airport terminal recently, much to the surprise of the conservators who had thought about cutting out the piece of wall to save it.)

This frieze is truly astounding: a whole history of San Francisco, from Native Americans to Spanish to ranchers, gold-seekers, Chinese workers, Victorian ladies, the 1906 earthquake, and the city’s status as “a community both international and unique.” In the weeks ahead, I will have more images and do more research on the community aspect of this art, but I thought this image provides a nice peek at the interior paintings, and connects to the urbanist ambitions of the artwork and the Home Savings bank — defining and promoting its community.

It is signed by Sheets and dated 1977; I am not sure who fabricated the image, but I am told he chose the wording. In terms of the art’s aesthetics, what comes to mind is A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884), George Seurat’s masterful, sun-filled pointillist work, on a grand scale. Sheet’s work here predates Sondheim’s musical based on the image, Sunday in the Park with George (the 1985 Pulitzer-Prize-winning play), but it does make me wonder how influential that image was in considering cultural nodes like San Francisco in the late twentieth century.

The painting’s San Francisco history does stop with the earthquake — sailboats and petticoats remain at the end of the image, not Haight-Ashbury or the then-current administration of the ill-fated George Moscone and Harvey Milk, among others.

The Sheets Studio artwork in general held images already old — a sense of nostalgia, but one informed by local history. Nostalgia is often seen as a reactionary force, but I think it is hard to say that here — so buoyant and optimistic, these images remembered happy times in the past, in order to encourage investment in happy futures.

Image of the Week: Stained Glass at Laurel Canyon

I have been providing an initial tour through all the media of the Sheets Studio artwork, and today we have arrived at stained glass. These can be some of the hardest images to photograph — even before we consider the banks’ restrictions on taking images only from the outside.

Millard Sheets and Susan Hertel were the primary designers of the images, and, in the case of stained glass, all the fabrication was done offsite; Denis O’Connor created the mosaics, working from gouaches and inverted cartoons and cans and cans of tiles. That was about all the labor they could handle in-house. Update: Brian recalled that the Pasadena stained glass firm was John Wallis Stained Glass, still active as John Wallis & Associates in Sierra Madre. Rufus Turner also indicates that Judson Stained Glass did commissions as well. Carnevale and Lohr, the Bell Gardens, Ca., firm recently involved in restoring the Rancho Palos Verdes mosaic working mostly in the iconic granite and travertine of these banks.

Both Hertel and Sheets had a lifelong love of horses, and here is yet another image where it shows: horses at the corral, young men and women out for a ride, and children being pulled toward fun by a woman at the reins. Other animals join in the fun — lots of dogs, and a few cats — and the bright, contrasting colors accentuate the theme of fun.

As I mentioned last week, these artworks could do a lot to set a happy mood in the bank — and of course the use of stained glass suggests the sense of awe inspired by walking into a darkened cathedral. The 1960s also saw the interest in Color Field painting, watching how one bright color would play off another; I see influences of that style and interest here, with the green moon, purple dog, bright green reins, and dappled blue- and orange-and-white horses.

These are commercial products — artwork sold to banks, that helped the banks’ bottom line — but they are also exemplary period pieces, valuable artworks from the time, which, as I have mentioned elsewhere, also tend to tell a story of California history. One hopes that JP Morgan Chase, as their current steward, understands the power and significance of these artistic bank assets.

Image of the Week: Home Savings Sculptures

The Pasadena bank at the corner of Lake and Colorado has been a focus of Home Savings art conservation in the last year, as Chase’s makeover of the location — new color palette, new entrance, new thick Plexiglass over the tellers’ windows — changed the experience of the bank radically.

The much-loved painting by Millard Sheets of Pasadena’s iconic Tournament of Roses parade was taken down, and as of last report, it is still seeking a permanent home in Pasadena where it will be both secure and on public display. (This report suggests the Pasadena Convention Center — as my history of this work will consider the interplay of public art and commercial spaces like banks, it says a lot about how society has changed that new venues being considered have to be public or nonprofit spaces, to guarantee the artwork, even despite the California law forbidding such artwork from being destroyed, regardless of location; see some discussion here.)

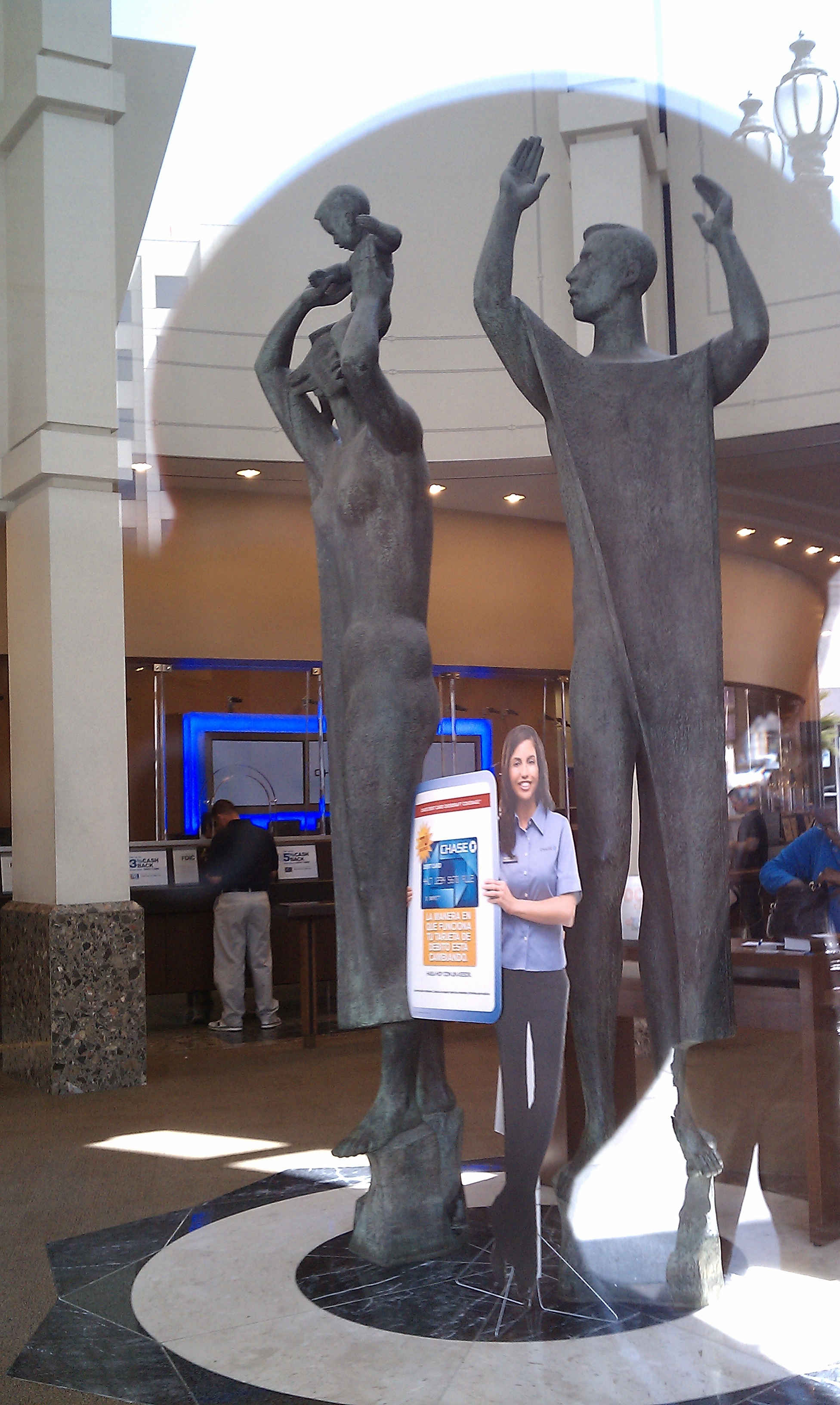

But sometimes lost in the discussion are the elements of the original Home Savings artwork that almost always remain on site: the sculptures. They are heavy, they tend to be more tall than wide, and hence even new arrangements seem to welcome them easily, even while divorcing them from their original context.

I have yet to figure out where (or if) the sculptures were signed, but I am told by Brian that the sculptors involved were John Edward Svenson and Albert Stewart. Some further information about them can be found here and here, respectively, but I must say they seem the most unsung part of the collection of artists and architects working in the Sheets Studio.

What to make of the sculpture? They are almost always family scenes, with some animals (dolphins on Santa Monica Blvd., for example). Men, women, and children enjoying one another’s company, normally in a nondescript way — walking, embracing, singing maybe. But not, say, driving, working, shopping, or, obviously, banking.

Like all of this artwork and architecture, the Sheets studio was working to create a welcoming space, with art that ennobled the experience of banking, and celebrated life — not in the means of the transaction, but in the life of that community, its history, and its pastimes. For a bank to endorse and pay for such work seems a throwback — though, I gather, these artworks paid for themselves in increased attention, increased deposits, and increased bank loyalty. Like the ongoing discussions of Mad Men‘s popularity and meaning suggest, perhaps it is this present-reality/past-ideals contrast that feeds the work’s unflagging popularity.

This week more individuals motivated by the cause of saving and understanding the art and architecture of the Home Savings banks have been in touch, and I appreciate it! I look forward to continuing to learn about this remarkable work, and sharing images and insights here on the blog, at the Urban History conference in October, and onward from there. Keep getting in touch!

Update: Thanks to an email from John Svenson’s son David, I have learned that the work above is Albert Stewart — and that his father, 87, is demonstrating his craft and signing books at the Millard Sheets Center at the LA County Fairplex this month.) He also noted that Paul Manship did the sculpture in front of the Hollywood bank. Thanks again for everyone who is adding information!