Image of the Week: Collaboration in Tujunga

Producing these intricate mosaics required a lot of work — negotiating with Home Savings about the location and design; creating a sketch; transforming the sketch into a full-color gouache; making a slide, to project on the wall to form a full-scale cartoon; tracing that cartoon in reverse, marking the colors, and then transferring it to the floor, where the tesserae could be cut and pasted in sections, only to be assembled on site into a right-side-up, all-mortared-together mosaic.

Needless to say, if one individual tried to do all that work alone–and then add architectural elements, stained-glass windows, decorative insignia on the doors and windows and cornice–it would take years, if not decades, to complete.

Some of that assistance might be seen as incidental to the artwork–I am no mason, but laying the mortar seems more workmanlike to me, for example–but others involved in the translation of idea into realized artwork clearly had to be artists in their own right.

While Millard Sheets was the face of the studio and the source of many of the designs, his closest collaborators were Denis O’Connor and Susan Hertel. Hertel was a painter in her own right, who worked in the studio creating the large-scale cartoons and doing most of the color selection; those I have talked to say her human figures are distinctive for their flowing lines. O’Connor, who had trained in the Royal Academy of Arts as a sculptor but had won drawing awards there, came to Claremont in 1960 and began work on the mosaics. And O’Connor and Hertel continued to work together on projects for Home Savings after Millard Sheets closed out his interest in the studio, in 1980.

Thus, when we look at the Home Savings art and projects like them, we have to keep in mind there is a vast team, including many artists, working together, and that the final signature — in this case, those of Hertel and O’Connor, indicating they may have conceived the design from start to finish — only reflects one or two of those involved with the work.

This week I had a chance to sit down with Denis O’Connor’s son, to hold some of the tesserae from the mosaics in my hand, to discuss the specific processes of making the tiles level and the design realistic. He has a great painting by Susan Hertel, showing the process of mosaic making — the work of men and women sitting around on the floor, surrounded by numbered cans filled with tiny pieces of glass, snippers in hand and the wheat paste nearby. I hope to speak to more of the mosaicists soon, but clearly a lot of drudgery came between conceiving of the design and seeing the final product, gloriously installed.

In terms of the artistry here in Tujunga, there are some interesting signs of the collaboration: the flowing plants and maternal figures, present in many of Hertel’s works, sit within the overall outline of a tree, a later and more sophisticated choice of design than the early, square mosaics. Millard Sheets collected Native American art, especially from the pre-Columbian period, and this work shows echoes of a large painting, signed by Sheets, in the Pomona First Federal building in Claremont, showing American Indian men gathering horses, and American Indian women, some bare-breasted, sitting in a circle.

Here, a Native American man holds a bow, while a Native America woman sits with a basket — perhaps reflecting the lifestyle of the Tongva, who gave the area its name. To the right, a vaquero roping a bull reflects the later Californio period. Do the stalks between them reflect wheat or bullrushes, agriculture or river foliage? Do most of the figures face right, to show the passage of time in that direction, or do they not engage one another to show a hostility, a pain between these communities? As I work with the preliminary sketches and correspondence about these images, I hope to find some answers.

The Latest: AAA Westways Feature on Saving the Art of Home Savings

Here’s the latest from a friend of the blog, Vickey Kalambakal, on Sheets’s work, and celebrating four of the works around the state: “Saving the Art of Home Savings,” for the September 2010 issue of Westways.

She discusses the partnership between Ahmanson and Sheets that created the string of banks bearing many of the iconic images, and the relationship between the Pomona bank tower and the pedestrian mall just discussed in the Image of the Week last Friday.

Brevity meant Vickey kept narrowly to these four images, with a concise description of how the banks and their art came to be, and how Tony Sheets, Millard’s son, sees the changing patterns of banking and bank security affecting the art’s display. But there is a great sense of those connections between art and place, history and community, on display there.

Vickey mentions the brochures that were available at the Hollywood bank, to identify and describe the artwork; it was titled “From Oranges to Oscars,” and I have recently seen a copy. I’ll be posting about it in the weeks ahead.

Image of the Week: Pomona Downtown Mall

When I started looking into the Millard Sheets Studio, I thought they primarily decorated buildings and spaces designed by others. What I have learned, however, is how important architectural designs were to the studio’s work. Sheets oversaw the architects who designed most of the banks where his studio’s mosaics, murals, and paintings appear, but he also oversaw the creation of other innovative urban spaces, built around community.

In 1962, Millard Sheets designed a downtown mall for his hometown of Pomona. By closing off a few streets, building fountains (like the one above) and adding sculptures, stone planters, and pebbled street, the mall turned a normal street into a pedestrian walkway, a mixed-use commercial space that welcomed shoppers, diners, and community events, from music to festivals to parades. (There is a nice history of the birth, death, and rebirth of the Pomona Downtown Mall here; this of course echoes a lot of what has gone on in New Urbanism planning in the Jane Jacobs-and-later era, and may have its apotheosis in the new, upscale creations like the Grove.)

This fountain demonstrates the marriage of Millard Sheets’ favorite themes — horses, nature — with this urbanist, community-driven desire. Nothing specific in the image speaks of history, but its location speaks to the importance of the Pomona community to Sheets, and the elements speak of friendship — two horses, not one; flowering branches of spring, not a lonely winter landscape.

In terms of preservation, this mosaic shows some of the ravages of being outside, with the calcinated California hard water constantly running; the pedestrian mall section was reopened to cars, and now the fountain sits a bit isolated. But the history the mall represents is still a powerful sign of the Sheets studio’s urban vision, one rooted in the history of California as they understood it.

New Feature: Millard Sheets Studio Image of the Week

I have lived in Los Angeles for a month now, and I have the chance to encounter the work of the Millard Sheets Studio constantly — when sought out in Pasadena, at the offramp to the Westminster Mall, all around the Claremont area. I have had the occasion to discuss my interest in the mosaics, murals, and sculptures with those who knew Sheets, with the children of those who worked in the studio, with (thankfully understanding) bank managers, and with librarians, curators, archivists, and historical preservation activists, whether professional or amateur.

I’m learning a lot about the process by which the art was conceived, designed, and created by Millard Sheets, Sue Hertel, and Denis O’Connor, and I am thinking more deeply about their influences and goals, and how it relates to my original desire — to learn how banks designed and decorated after World War II came to reflect the earliest histories of California, as well as the region’s glorious flora, fauna, and diversions.

I am working on a new database, using lists from the Huntington Library and the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, to create a complete list of the Sheets Studio’s creations, the designer and date — as well as their current status as safe, lost, or threatened.

To start rolling out those ideas, and to keep the slew of other professional work (like my just-finished book) from sidelining this investigation, today I inaugurate a new series on the blog: Millard Sheets Studio Image of the Week! I’ll pull an image from my travels, or my extensive archive of Sheets-and-co. images, and give you a sense of what I think we’re seeing.

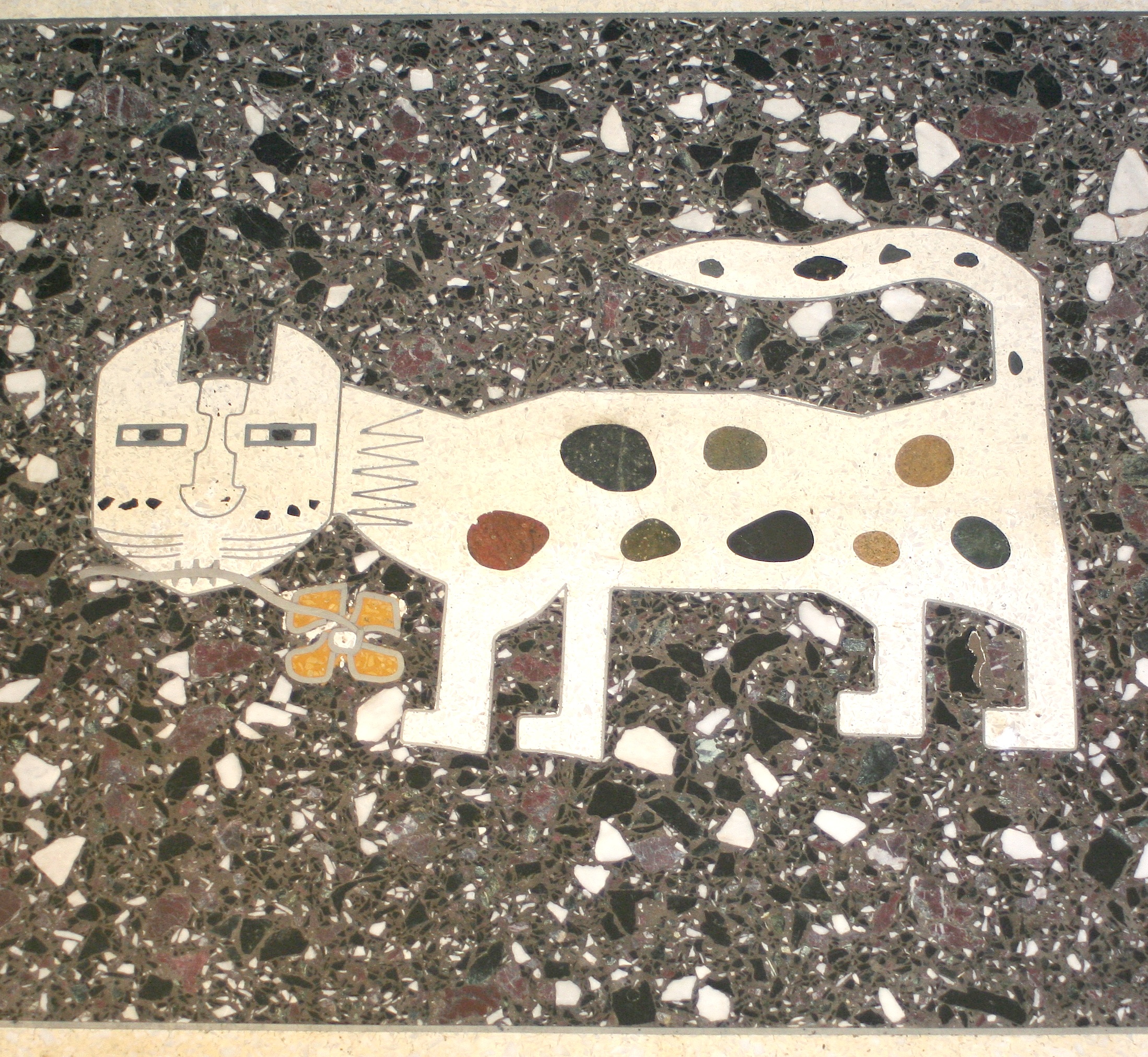

Above is a small, whimsical Sheets creation in an unusual plane for the studio’s work — the floor! As you enter what was the Sheets-and-co. studio at 655 E. Foothill Ave, you would have encountered this cat, ready to greet you with a flower in its mouth. (The current ophthalmology office still uses the same reception area, but they had the cat covered with chairs.)

I visited the office yesterday with Brian Worley, a Friend of the Blog and a onetime worker in Sheets’s studio, helping with everything from background work on the mosaics to installation and documentation of the work once completed. The visit will provide a lot of images and information, but today I’ll relate how this cat came to mind as the perfect image of what I now know about Sheets — curious, creative, and seeking to infuse his designs with joy and fun.

The work of the Sheets Studio has a lot of animals, a lot of families in loving embraces, or out having fun, and the artwork of the studio complex (more in coming weeks) reflects this interest. Brian told me there used to be a birdcage right in the center of the two buildings, their color, activity, and song presumably filling the space between Sheets’s office and the large production studio, the shelves stacked with cans of mosaic tesserae.

So Sheets’s clients would see the exterior decorations, hear the birds, and then come inside to await their appointment — and see this wonderful cat, embracing the moment with a flower in its mouth.

We can feel welcomed to explore the Sheets Studio work, too.

Revving up – and presenting in October

Hello again!

With the boxes mostly unpacked and lots of folks away on summer vacations, I am finding a chance to get back to search for the works of the Sheets studio. I have a checklist of about one hundred Millard Sheets news items, tips from readers, and more to follow up, so as I process them there should be lots new on the blog.

Also, I have learned that my paper on these murals and their meaning was accepted for presentation at the Urban History Association’s biennial meeting in Las Vegas, October 21st at 10:30am. (Program here).

Paper proposed for a panel on “Urban Historians and Foundation Myths,” Urban History Association conference, Las Vegas, October 2010

My paper is titled “The Memory of Californios in Nixonland: History in Millard Sheets’s Home Saving Murals,” and will appear as part of two panels on “Urban Historians and Foundation Myths,” alongside work by Bell Clement on Washington, D.C,; David Schley on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad; and Bill Issel on San Francisco. I am looking forward to it.

Finally, when I went out to the movies with The Blog’s Partner the other night, we walked right by the exquisite mural at Sunset and Vine (above), and I felt happy once again to be living in LA. I snapped this photo from my newest smartphone, just after sunset.

So watch this space for… weekly?… updates in the months ahead…

Now living in LA

Hello everyone!

The semester is over, and the sun is out here in West LA — the new home of these blogs!

(We went to the beach yesterday, and did not drive by this mosaic, but we could have. Any news on the building’s status? I hear it is/was between owners.)

Thanks to all those who have continued to comment and add locations to the Home Savings blog, and to those who have expressed interest in the Civil War Era in the American West.

We are still unpacking boxes and getting our coordinates, but I wanted to let you know that new posts will be coming soon — and I will have a chance to check out more sites in the Southland in person, at least during the summer and other school breaks.

More in the days and weeks ahead–

The Civil War in the Trans-Mississippi West

The Civil War in the Trans-Mississippi West: Building a Network

A St. Louis merchant arrested in Montana for his Confederate sympathies.

The capture of Mesilla, New Mexico, and the establishment of the Confederate state of Arizona.

Visions of slaveholding in southern California.

The betrayal of loyal Union allies in Indian Territory.

The United States Colored Troops battling along the Mexican border, ready to receive the surrender of the last major division of the Confederate Army, and learning of Lincoln’s assassination.

The fruits of victory evident in new universities founded for African Americans in the West, and in the completion of the transcontinental railroad.

The war’s conflicts continued on Indian reservations, in the racial conflict over property rights, in battles for salt and for railroad-labor cowboying contracts.

*

As we approach the Civil War’s sesquicentennial, it is important to recall how the battles, struggles, and conflicting visions of the Civil War era stretched beyond the Mississippi River, into the western territory seized by the United States from Mexico and American Indian nations.

Gettysburg was an epic battle; Charleston Harbor saw many of the war’s turning points; the battlefields of central Virginia again and again were soaked with blood. But the war in the West – not the so-called “western theater” of Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Missouri alone, but the skirmishes, tensions, and near-misses in the wider trans-Misssissippi West – have crucial stories to tell us of the Civil War and its impact.

*

This blog post is merely intended to announce our interests in gathering scholars and members of the public around the task of recovering, researching, analyzing, and commemorating the history of the Civil War in the trans-Mississippi West. In the years ahead, those connected to this network will plan panel discussions and conferences, edited volumes, and book presentations on this vital subject of research.

To get involved, please contact our coordinator, Adam Arenson, assistant professor of history at the University of Texas at El Paso. Please share your ideas, your knowledge of work in progress, syllabi, bibliographies, and more. And watch this space for further information about the fascinating stories of the Civil War in the trans-Mississippi West.

Cataloging the Home Savings artworks

I have had a chance to rearrange the website.

The list of artworks commissioned by Home Savings of America for its bank branches — murals, mosaics, sculpture and more — plus other work by Millard Sheets and his studiomates has been updated here.

The Legacy of Millard Sheets

Happy 2010! So far, January has proved to be a month of intense interest in Millard Sheets — art museums, city historic-preservation offices, and enthusiastic fans of Sheets’s style have been contacting me constantly. Glad for the attention to the website, and to Sheets’s work!

Elsewhere I will update the list of known Sheets public artwork; here I want to think about Sheets’s legacy.

Valley reader K sent along these photos of a stone-clad bank at 13949 Ventura Blvd, in Sherman Oaks. Built in 1989, it is a late Home Savings with frescoes of California history:

These images evoke the California Mission past — bells and vaguely Spanish, vaguely ecclesiastical architecture — with male figures engaged in plowing and (perhaps) seeding among the trees, old wooden instruments intended to heighten the sense of nineteenth-century nostalgia.

Many of Sheets’s works seem a bit more historically grounded to the locale– a conquistador in full attire at a bank in San Diego, a Victorian woman with parasol in San Francisco– though some of the images of horsemen might fit the same imagined time.

Any thoughts from you, readers, on what legacies of Sheets these images display? Clearly, the bank saw the continuation of Old California images as part of its identity. But does the chosen image tell us anything specific about Sherman Oaks? (I guess those are oak trees, so there is a local connection.)

Please let me know what you see, and keep spreading the word!