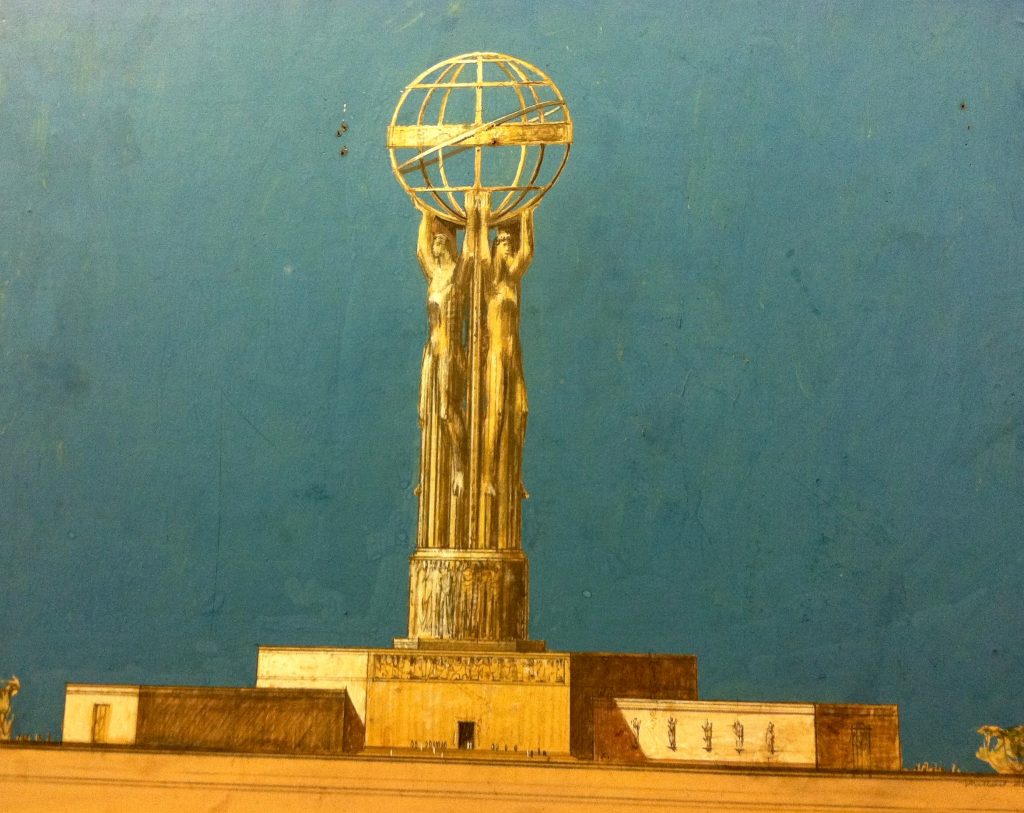

Millard Sheets, sketch of Monument to Democracy for San Pedro, 1954. Courtesy of Alan Wofsy Fine Arts; my crooked image.

The L.A. Conservancy tour, like many of my efforts, focused on preserving the art and architecture of the Millard Sheets Studio, and to understanding what it has meant for its communities.

But, like all artists and architects, there are the projects that didn’t get built. And unbuilt projects can often be fascinating in their counterfactual, floor-moving-under-you way, a vision of a city unvisited yet so familiar.

This statue seems the biggest unbuilt project in the Sheets oeuvre: the Monument to Democracy, a 1954 effort spearheaded by LA County Supervisor John Anson Ford to build the Pacific Ocean’s “Statue of Liberty” companion in San Pedro.

Statue of Liberty replica in Guam. Photograph c. 2004 by Douglas Sprott under Creative Commons license Flickr

“The erection, on the West Coast, of an heroic statue to Democracy…is a project combining considerations of statesmanship, education and art, of profound international significance,” Ford wrote. Echoing age-old themes with a new Cold War twist, Ford declared,

The course of Democracy is moving westward. The great nations about the Pacific basin are looking across to America trying to discern whether our Democracy is really something for all, or is in effect a concept reserved for the Anglo-Saxon. Communism tries with cunning and skill to alienate all of darker skin from the ideals that motivate our Western society….When this project becomes a reality, as it certainly must, countless millions will find their way to it, there to be inspired by its majestic symbolism, and there to learn something of the unending story of how Democracy has inspired and blessed mankind.

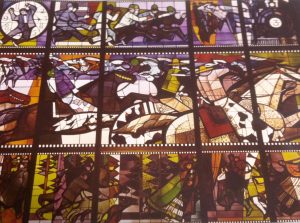

Intended to be 480 feet tall, on a drum base 46 feet hight, topped with a bronze globe 125 feet in diameter, the Monument to Democracy was to have three figures, each 250 feet tall, on top of historical and art museums revealing the progress of each of the world’s races toward democracy. (I guess we are talking Asian, African, and European here — not a period of much considered of indigenous American peoples.) Millard Sheets was listed as the project’s designer, with the statue to be designed by his colleague, sculptor Albert Stewart.

This funding prospectus was circulating just as Sheets was completing his first project for Howard Ahmanson, the remodel of the National American Fire Insurance building, then at 3731 Wilshire (now the site of the Ahmanson Center).

If Sheets and Stewart were to have become wrapped up with this statue/museum project, how different southern California would look! One iconic statue, for good or ill, would have replaced the effort, history, and messaging that Home Savings received, to different ends.