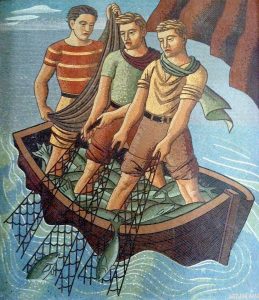

Denis O’Connor, Sue Hertel, and Studio MosaicArt di D.Colledani-Milan, mosaic, Savings of America, Springfield, Missouri, 1986. Note the goof that reversed the SH of Sue’s signature at bottom right.

Mosaic is an ancient art. Around the Mediterranean, but especially in Italy, mosaic traditions go back millennia. And there was nothing obvious about Millard Sheets’s decision to include mosaics in his initial designs for Home Savings — though, along with stained glass, travertine, gold leaf, and classicist references in modernist designs — they contribute to Sheets’s goal of helping a new financial institution feel timeless, perhaps even eternal.

Lillian Sizemore, a mosaicist and a scholar of mosaics, has helped me understand more about the unusual/innovative choices made over the decades by the Sheets Studio, primarily by Denis O’Connor, in the fabrication of the Home Savings mosaics. She and I have discussed how the Sheets Studio likely garnered its mosaic skills from Arthur and Jean Ames, who created New Deal-era mosaics at Newport Harbor Union High School, and taught technique to students (including Martha Menke Underwood and Nancy Colbath) at the Claremont Colleges.

My research has suggested Millard Sheets first designed mosaics that were fabricated by the Ravenna Mosaic Company of St. Louis, in the 1930s and 1940s, before building his own fabrication team. And, like mosaicists around the world, the Sheets Studio ordered its best tiles from Italy (with some additional ones from Mexico), making it hard to use materials to track the mosaic fabrication process.

What we see here is the other end of the spectrum — when, after Millard Sheets retired, Denis O’Connor and Sue Hertel continued the business — they became overwhelmed by the requirements of the rapidly expanding Savings of America.

Lillian has helped me see how and where O’Connor ordered mosaics to be fabricated in Italy, at less cost, via a broker named Franco Merli at NOVA Designs. (Denis segregated the records about these Italian-fabricated mosaics, either as a matter of file management or to keep this change out of the spotlight.) The work was done by Studio MosaicArt di D.Colledani-Milan, which has a nice website highlighting their ongoing mosaic work.

Offshoring the mosaic fabrication was cheaper, but, as Lillian has shown me, it also led to changes in the fabrication techniques, which she is tracking. Unfamiliarity with the themes, figures, and even animals intended by the sketches lead to discussions, in a mix of Italian and English, in the files.

This mosaic, in Springfield, Missouri, then suffered another goof — the fabricators did not correctly reverse Sue Hertel’s initials — and no one at the installation noticed to fix it.

For one of the new national Savings of America branches, far from other branches and from the context and story of the Sheets Studio and Home Savings, this was insult to injury.

One expects there were foreheads smacking from Missouri to California to Italy when the mistake was pointed out.