The Art & Architecture Case Study houses and the Monsanto House of the Future were never mass-produced, even though both concepts were created with that goal. Why? The Monsanto house, intended to be cheap, modular, and replicable, was not; the Case Study houses, made out mass-produced industrial materials, could not find financing from lenders worried they were atypical, too small, too unusual.

I finished my grading for the semester and I rewarded myself with a trip to the Getty to see the Pacific Standard Time Presents exhibition, focused on LA architecture in the period of the successful PST art shows, 1945-1980. (Glad to be back on the blog; I have a lot of writing and research commitments in the months ahead, so my pace may slow down–but some of what you don’t see here will eventually mean more articles, books, and exhibitions on the Sheets Studio and the Home Savings and Loan influence, so don’t despair!)

At the exhibition, I found a lot of what you might expect as touchstones in a postwar LA architecture-and-urbanism show — the car, Googie, the freeway system, aerospace, LAX, Sunset and Wilshire streetscapes, Disneyland, Mid-Century Modern houses, the Music Center, Bunker Hill, the Watts Towers, the Chavez Ravine evictions and Dodger Stadium, the Walt Disney Concert Hall, and concepts, built and un-built, from big-name architects from Lloyd Wright to Frank Gehry to Morphosis. If, like the PST shows, the PST Presents shows are setting a baseline for the history of LA postwar architecture, this is all required for the survey.

Then there were the pleasant surprises: the focus on religious architecture, from an un-built mosque designed by Richard Neutra and Sinai Temple by Sidney Eisenshtat to churches, large and small, architect-designed and vernacular storefronts. I thought the attention to dingbat apartment buildings and Park La Brea was great, as well as the discussion of architecture for retail space, from the Kate Mantilini restaurant to Universal CityWalk, and the architecture paid for by higher-education institutions. The single biggest eye-opener for me was the temporary architecture and design work done for the 1984 Olympics — the video segment, all hot pink and electronic music, evoked the age wonderfully.

The Getty is an art museum, and their engagement with architecture here is mostly aesthetic — beautiful drawings, photographs, and models, and not a ton of text on the wall, advancing contextual or historiographic arguments. Maybe my years as a professor are getting to me, but I like a strongly argued exhibit, and I didn’t see any strong argument here (other than those made at the level of inclusion and exclusion). I flipped through the essays by noted historians and architectural historians, among others, in the 300-page accompanying volume, and I found mostly overviews of the existing consensus on suburbanization, LA’s relation to open space, to freeways, its architectural schools and the like — nice, but I am not sure they rise above the reference-work level.

And, throughout the exhibit and 300 pages of the book, there was no reference to Millard Sheets.

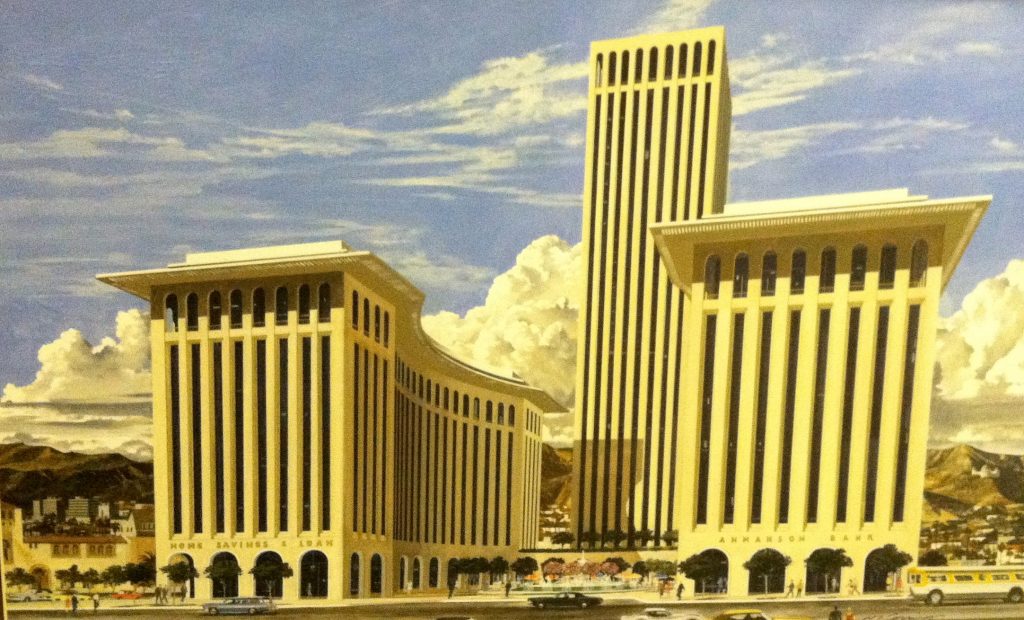

Of course this blog is biased on that point. And there was a large drawing of the Ahmanson Center, with the Home Savings & Loan name prominently displayed, in the exhibit. Choosing the most atypical Home Savings & Loan design, by big-name architect Edward Durrell Stone rather than the Sheets Studio or Frank Homolka, demonstrates the show’s biases. The financing of homes gets a mention in the book, though no discussion of the specific role played by the S&L’s in financing and promoting LA’s main-commercial-street-and-tract-home-suburb-connected-by-freeway vibe. Howard Ahmanson’s name doesn’t appear – and they don’t have Eric John Abrahamson’s great new book for sale (nor anything by architectural expert Alan Hess).

Edward Durrell Stone, Ahmanson Center color sketch with unrealized tower. Courtesy of the Ahmanson Foundation

And that got me thinking: Who paid for it?

Who paid for Googie architecture, and the Disney Concert Hall? Who paid for the Case Study homes, and the imagineering of Disneyland? You show me the gleaming cars and the drive-ins, but who was the customer, and who the producer? What economy made this possible, and what happened to that economy since?

I know the answer, and you may too, but it felt like the economic history of architecture and urbanism needed a larger role. The classic commercial and civic architect of LA in these years is Welton Becket — his name and designs are all over the exhibit, on almost every wall, but we get no image of him (except in a video of the dedication of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion) and no discussion of his life, his views, his experiences. (It doesn’t seem anyone has written anything significant about his firm in decades — a great research opportunity!)

I am not asking for Millard Sheets and his studio to be featured. But it seems not giving this attention to Becket (or any of the other architects) means we don’t learn what vision they had, how they were trained, who paid the bills, and what constraints they faced. In urban architecture, especially for commercial or civic clients, these seem essential concerns.

Perhaps this is what makes me a historian first, interested in politics, economics, and then culture, rather than an art historian. But it felt like ignoring the industry and financing of the architecture left the exhibit a bit shallow.

If the goal of the show was to demonstrate how LA constructed a futuristic city, isn’t the financing, the politics, the urban planning, the historical and political context, and the public reaction important? Those motivations drive my interest in the Sheets Studio work for Home Savings & Loan — why a commercial enterprise would invest in first-quality art and architecture in these exact years, depicting southern California community history and events, in an effort to change the landscape and cement their legacy.

Business, economics, and politics behind (and, often, in) art and architecture — seems like pretty powerful stuff to me. It will get its due in my Home Savings book and exhibit, one of these days. Perhaps the Getty can help us see these connections for the architecture and urbanism they have on display — in their next PST exhibits?