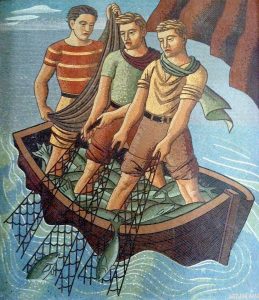

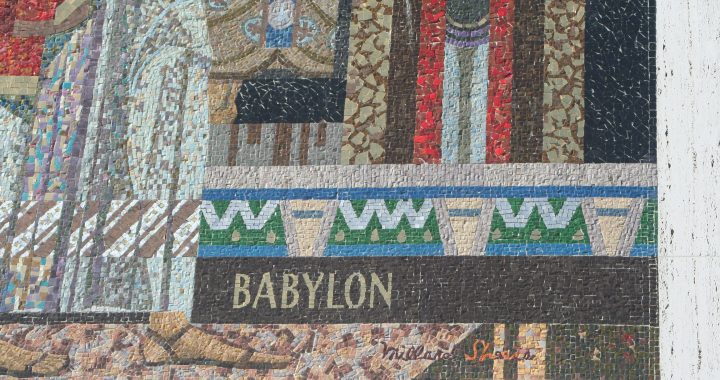

Millard Sheets and Studio, Scottish Rite Masonic history mosaic, 4357 Wilshire, 1963

Last week, I was able to drive along Wilshire Boulevard and see my local string of Sheets Studio art: three banks and this monumental building, the four-story former Scottish Rite temple designed and decorated by the Sheets Studio in 1963.

The property is currently for sale; the Los Angeles Masons (Scottish Rite is one of the traditions of the Freemasons, a fraternal organization with many ties to the symbolism of the United States, as Nicholas Cage and Dan Brown remind us) lost a series of court cases over noise complaints and zoning for the building, and as of 2008 the California Supreme Court denied them the right to lease the property for commercial use.

The legal fight means that the building has been mostly closed since 1993, and completely closed since 2006, so I have not been able to see the Sheets Studio work inside the building (which I hear is extensive).

George Washington, Mason, at 4357 Wilshire

4357 Wilshire entrance, with text drawn from U.S. founding documents

I provide here only a few examples of the sculpture and quotations from the building; following the tradition of Masonic structures such as the ornate George Washington National Masonic Memorial, built in 1932, that bridge the known history of the Masons (reaching back to the Enlightenment) with the order’s mythology, reaching back to the time of King Solomon’s Temple, with (as this mosaic and group of sculptures gives evidence to) detours into the law-giving and correct-living precepts of Hammurabi’s Code, a number of early Greek and Roman leaders, the builders of medieval cathedrals, Renaissance leaders, and finally American Founders. As anti-Masonic conspiracy theorists are quick to point out, the vast majority of U.S. Presidents have been Masons, along with other kinds of community leaders. But, without any internal knowledge, I have always seen that as a reflection of these individuals’ power, respect, acumen, and ability to network, rather than its cause.

From what I gather, the 1950s and 1960s was a high point for recent Masonic activity in the United States — a premier networking and campaigning venue, among an association of the established. And, as the later zoning fight about this building reveals, the prominent location on Wilshire, in what is otherwise a residential neighborhood, flanked with massive Protestant churches, indicates the influence of the Masonic group that built this structure.

Detail of Babylon with signature, 1963

Two elements of this mosaic interest me, the first being its deeply historical nature. Did this commission push the Sheets Studio toward using more history in the Home Savings banks? Next week I will discuss the first Home Savings location, also on Wilshire, that has a mix of historic and ahistorical imagery. Sheets spoke about how he had almost no guidance from Howard Ahmanson–simply a directive to make the art beautiful. Clearly the Masons had very specific ideas about who should be highlighted, what text should be included, and what gestures, symbols, and clothing would best express Masonic principles. I wonder if Sheets and his collaborators enjoyed the research project, and/or if the reception suggested more historical images would work well.

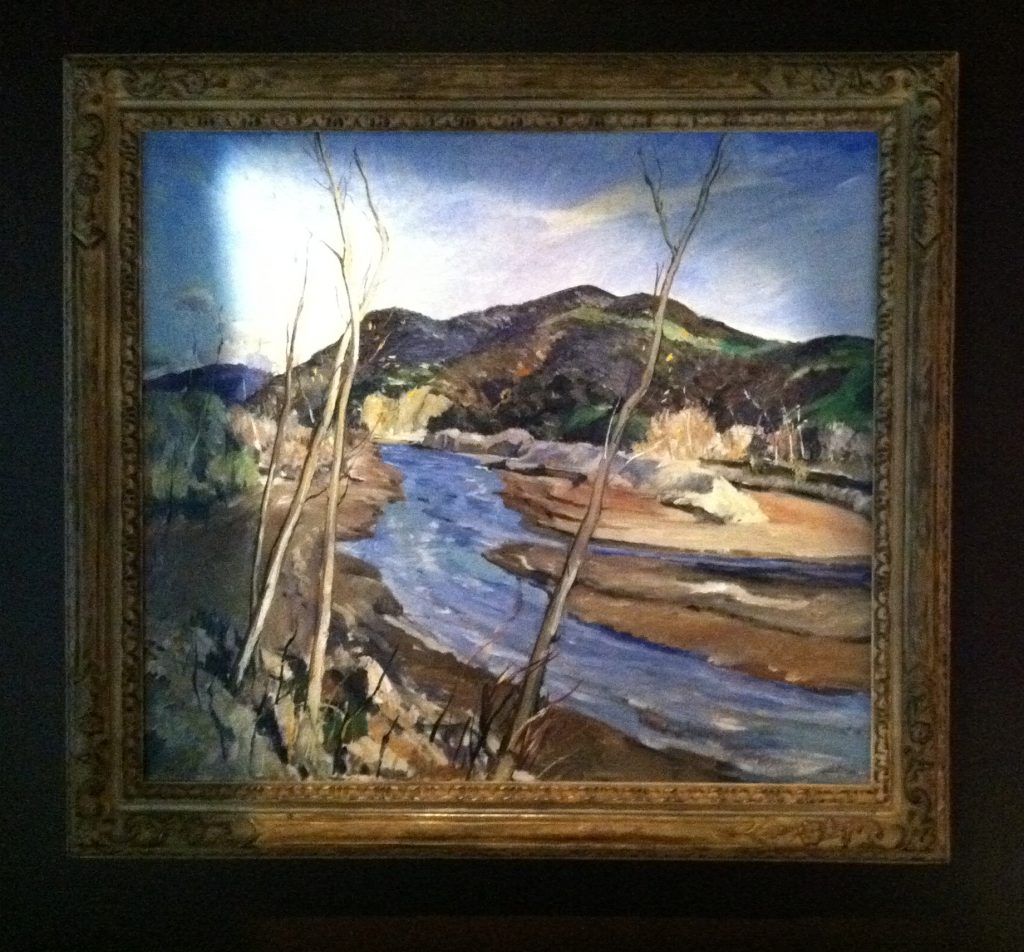

The other element is the mosaic’s style. Thanks to my experience with Alba Cisneros a few weeks ago, cutting tile and comparing Byzantine and Italian tile styles, I can recognize this Scottish Rite mosaic as a transitional moment. In his oral interview in the 1980s, Sheets discussed how the original mosaics were made in Italy, but that, given his disappointments with the results, he began to train himself and his studio in the creation of mosaics. This mosaic was made in California, but the signature technique — Byzantine tile, carefully cut and shaped — is not present throughout; there there are large sections of flat, square Italian-style tesserae, which are machine-made. Perhaps the sheet size of this four-foot mosaic is to blame, but I wonder if Sheets, Denis O’Connor, and others were still perfecting their mosaic tile. More interviews and more time in the archives will tell.