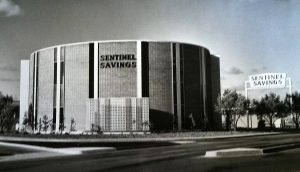

S. David Underwood, Sentinel Savings and Loan, San Diego, 1962 (demolished); photograph by Busco-Nestor Studios. S. David Underwood Archive.

In July 1948, Millard Sheets typed up a followup note to Jack Beardwood, a TIME bureau chief and Millard’s connection to LIFE magazine. “It just occurred to me,” he wrote, ” it might be wise to suggest…that the magazine should not use the word ‘architect’ in the article in connection with my name.” As Sheets noted, “not having an actual architectural degree, along with many others who design,” he had no need to claim the title and “wav[e] a red flag in front of the A.I.A.,” architecture’s national professional association.

Sheets made clear that he did the overall design, approaching it as art in its totality–but that there was always an architect there to sign off, to make working drawings, and to see to it that regulations were followed. In the letter from 1948, Sheets mentioned Benjamin H. Anderson as the architect of record on the air school projects; as we have discussed here, Rufus Turner has shared memories of the studio beginning in the late 1950s.

But, as soon as there was a Sheets Studio to be part of, the studio’s principal architect was S. David Underwood. Rufus Turner has memories of seeing Underwood hard at work in Sheets’s large personal studio at the Padua Hills house–and even of Underwood having a cot there to sleep, before the Foothill Boulevard studio was constructed, after a 1958 groundbreaking.

Born in Montreal in 1917, Underwood had grown up in Glendale, California, and his first commercial architecture was for a schoolmate, Robert C. Wian, designing distinctive, “landmark” architecture for the new branches of his hamburger stand, Bob’s Big Boy. This iconic work (see next week’s post) stood out among roadside architecture, much as Sheets would need for Home Savings.

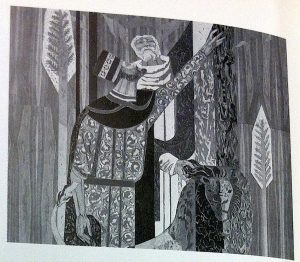

Underwood came to work with Sheets in 1955, just as Sheets’s work in murals and interior design was blossoming into the design of complete buildings, with the mainstay of the office’s work, at the behest of Howard Ahmanson, begun with a phone call in 1953, for both Home Savings (Underwood worked on 16 locations, 1956-1962) and Guaranty Savings and Loan (three locations, including Redwood City) in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Underwood made all this work possible, Sheets understood. Millard wanted to sketch the silhouette of the building and design its artistic flourishes, but he wanted someone else to decide how to route the pipes, support the roof, or create drawings for permits and contractors. This synergy of vision and technical details was all necessary for the art to emerge–and the next few weeks will highlight these designs, from subtle to spectacular.

Like the work of Sue Hertel, Denis O’Connor, David’s wife Martha Menke Underwood (married in 1962, they divorced in 1979) and others in the Sheets Studio, Dave Underwood’s work was publicly regarded as Millard Sheets Studio work, without much room for individual credit.

By 1962, Underwood left the studio to set up his own architectural office in Claremont, though he continued to collaborate with Millard Sheets on some projects, including the Garrison Theater (updated link here). Underwood continued to design buildings, including a lot of distinctive office space in Claremont, including the San Jose Avenue office building for the Carpenters’ Union (updated link here), and the Midland Mutual Insurance building at Harvard and Fourth, until his retirement in 1990. Underwood died in 2002.

As all the references above suggest, there are a lot of buildings I could have chosen to introduce Underwood on the blog. But one stood out–because it was a memorable landmark of my childhood.

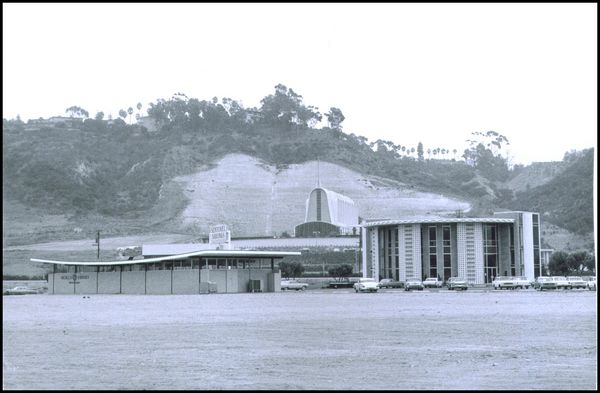

S. David Underwood, Sentinel Savings and Loan, San Diego, 1962 (demolished); S. David Underwood Archive.

The Sentinel Savings and Loan building was built on Camino del Rio North in San Diego, near the intersection of Interstates 8 and 805 was constructed in 1962, one of Underwood’s first projects to be listed under his own architectural firm, after his time with the Sheets Studio.

As this photograph demonstrates, by 1965 the Sentinel Savings building anchored a trio of distinctive modernist structures in Mission Valley. In 1971, Sentinel Savings was purchased by Great Western, the name on the building in my childhood. Of these three, now only the First United Methodist church remains.

Though quite different from the Sheets Studio architecture for Home Savings, the clean geometric lines, use of solid and airy forms, and the use of the tall interior space suggested some of the same eye-catching choices, and show also the affinity of all this bank architecture to some of the most well-regarded examples of Mid Century Modernism. (See this example, a round bank in Sunnyvale from 1963 — is there some direct link to Underwood?)

Come back over the next few weeks to see more examples of Underwood’s work, before, during, and after his Sheets Studio work.

Thanks to Brian Worley, Rufus Turner, Steve Underwood, “Adrian Chapelo,” and Jane Kenealy of the San Diego History Center for their help with information for this post.